- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Inside a museum of broken memories and families divided by war

Mohammad Ali was in his early 30s when the India-Pakistan war of 1971 separated him from his wife for ever. Overnight, the couple found themselves on opposite sides of the LoC. While Ali was in Hunderman village, his wife had gone to her native Bilargo village — and between them lay a newly drawn border that sealed their separation. Over the years since Independence, Hunderman,...

Mohammad Ali was in his early 30s when the India-Pakistan war of 1971 separated him from his wife for ever. Overnight, the couple found themselves on opposite sides of the LoC. While Ali was in Hunderman village, his wife had gone to her native Bilargo village — and between them lay a newly drawn border that sealed their separation.

Over the years since Independence, Hunderman, 10 kilometres away from the main town of Kargil along the LoC, has witnessed four wars and a number of skirmishes — all ending in broken homes and hearts for villagers like Ali. The village was part of Pakistan from 1949-71. After the ’71 war, it came under India.

While the world remembers the 1971 India-Pakistan war for the liberation of East Pakistan and the formation of Bangladesh, scores of families across the border in Ladakh were separated by a cruel stroke of fate. As five villages of Turtuk in Leh and Hunderman village in Kargil came under Indian control following the war, many from the same families became citizens of two separate countries divided by an unpredictable, shifting LoC.

The volatile border has not allowed the village to prosper much in terms of development even as it often faces drought in summers.

But 35-year-old Ilyas Ansari wants to change this war-ravaged image of Hunderman and, at the same time, hold on to the history of the place — the way it was once long before war touched it.

Holding on to history

In 2016, Ansari converted his ancestral home in the village into a museum with the help of Kargil-based Roots Ladakh that promotes adventure, educational and rural tourism in lesser-known parts of Ladakh.

Muzammil Hussain, founder of Roots Ladakh, says, “We identified the village for the first time in 2015 and slowly came to know about its importance — its colonial history, historical importance on the Silk Route, and later the stories of divided families.”

What attracted his team most was the typical Himalayan vernacular architecture of the village. “One can see beautiful stones and willow work on the houses. Besides, the rare concept of wooden plaster used in the structures.”

The initial idea, according to Muzammil, was to turn the village into an architecture residency. “We initially thought we could invite experts and artists for residential workshops and homestays, but the concept could not be implemented due to some restraints.” The museum came up and later Muzammil handed it over to Ilyas.

Ilyas has provided two rooms of his old home for the two galleries of the museum.

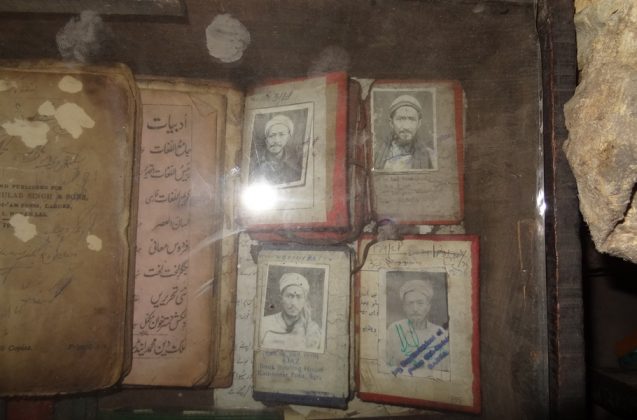

What makes the museum special is its location along the LoC and the stories of separation around it. “Moreover, the material artefacts in the museum belonged to people who used to live here and died. Some of the things belonged to those who left for Pakistan, leaving behind their belongings here,” says Ilyas.

Most artefacts, however, are from the personal collections of Ilyas that remained in the house for years.

Ilyas says Ajaz Munshi, a cultural activist and historian, helped him understand the value of these artefacts, which included coins and other items that dated back to decades.

As the name — Museum of Memories — suggests, it is essentially about memories of people who either left for their heavenly abode or were left on the other side of the border.

Ilyas says that the main items with which he started the museum belonged to his paternal uncle, who during the 1971 war had gone to Baltistan and could never come back as the border was drawn after the war.

“Whenever some tourist spots an old perfume bottle or grocery items that once belonged to my uncle, they are surprised by the fact that such popular brands that were available in cities were consumed by people in these far-flung areas as well,” he smiles.

Ilyas takes immense pride in displaying the memories of his dear ones for the visitors to understand the lives of the people of Hunderman. He feels what makes the museum special are the memories of his ancestors associated with these old items, particularly of his late uncle Haji Ghulam Mohamed. Some of the museum items also belonged to his maternal uncle. Both the men were separated from Ilyas’ family during the 1971 war.

Lives torn asunder

During the war, Haji Ghulam went to Bilargo in Baltistan, looking for his sister-in-law and Ilyas’s mother Zahra thinking she had gone there. He, however, didn’t know that she had actually gone to neighbouring Mal village. As the war ended and the borders were drawn overnight, Haji Ghulam remained stuck in Bilargo (Pakistan) while Hunderman came under India’s control.

According to Ilyas, Haji Ghulam wrote several letters to his family that mostly reeked of intense pangs of separation. “His letters are a testament of his loneliness,” Ilyas says.

In one of the letters, Haji Ghulam writes: “In your last letter, you guys asked me if I have married here again. But to do so I need a family. Who will make the arrangements. “Pardes mein ghairo ke beech kuan meri shaadi karwayega (I don’t have a family here, who will take the pains to get me married in a foreign land)?”

Ilyas gives the backstory to his uncle’s first marriage with a Ladakhi girl in Skardu that didn’t work. The uncle was also thrown out of his job and used to live with his elder brothers and their families in Hunderman.

In another letter, Haji Ghulam complains to his family that other people get gifts from across the border. But he will be happy even if his family bothers to write him letters that he could keep as souvenirs.

“These letters are part of this museum. It is through such documents that the people who come here get an idea of the pain of separation that the borders have inflicted on our lives,” Ilyas says.

Haji Ghulam’s story met an unhappy ending as the man died in ‘exile’ a few years back, lonely and separated from his family.

Ilyas recalls that during the 1999 war, when he was studying in Kargil town, one of his uncles used to accompany him every time back to Hunderman even though Kargil town was quite safe compared to Hunderman.

“Now I realise that my uncle did not want a repeat of the separation of 1971 war. He used to say ‘marney se zyada judaai ka gham hota hai (separation is more painful than death’).”

Ilyas’s family on both sides is riddled with such painful stories. For Zahra, it was not just her brother-in-law who was taken away by the border, but it also separated her from her parents, brothers and sisters in Bilargo village.

“We often miss their presence during festivals and other important events of our lives. However, now through social media at least we can interact. My mother got the first letter from her family 10 years after the 1971 war. It made her very emotional… but time heals every pain.”

Recording the present

Once when a relative was going to Pakistan, Ilyas thought of recording the voices of people on this side to send them to their family members living on the other side of the border. To his surprise, the recordings filled 32 GB data. “In every village, there is someone who was torn apart from relatives. The number became all too real when simple messages with greetings and prayers filled 32 GB data.”

When asked if she longs to go back to Pakistan to meet her relatives, Zahra says she thought of going several times but was forced to drop the idea every time due to financial constraints. “Going through Wagah costs a lot.” Zahra’s only hopes are pinned on the opening of the Kargil-Skardu road.

Once Zahra’s brother threw around the idea of a possible reunion during Hajj in Mecca. But again, her financial position didn’t allow her to take the journey.

A few years back, Ilyas connected his mother with his maternal uncle in Pakistan through a video call. Although Zahra couldn’t be happier to see her brother at long last, what she said after disconnecting the call, Ilyas says, will remain with him forever.

“My mother said she was happy that it finally happened but also sad that even though she could see him after all those years, she couldn’t actually meet him or touch him. That this will pain her all her life.”

New beginning with old stories

Hunderman was connected by road only in the early 2000s. Before that, there was hardly any exposure to the outer world. However, this museum has helped change the lives of the people to a certain extent as it draws a lot of visitors and media attention.

“Several authors, documentary makers, journalists, photojournalists, architects and tourists have visited the village due to this museum in the last few years,” Ilyas says.

“Earlier, our presence was not even acknowledged at official gatherings. But recently, I represented Hunderman during a meeting with the Lieutenant Governor of Ladakh. Also, during a meeting at a university in Chandigarh, faculty members already knew about my village. I couldn’t be happier,” he smiles.

The fact that these families have learnt to remain happy with whatever life doled out to them is visible from the smiling face of a weather-beaten Mohammad Ali.

After he was separated from his wife, Ali waited two years for a miracle to unite them back. But he finally realised that was not going to happen.

“I waited for two years and then realised borders are a permanent reality. So, with a heavy heart, I sent her a divorce letter to Pakistan.”

He is happy that the divorce helped her resettle in Pakistan. She remarried and has two children who have grown up now.

“I believe in living a life with no regrets. I too got married again and have kids.”

Ali flashes a smile as he proudly says that all his children earn enough and he can afford to take it easy now.

He believes that harping on the past won’t bring it back. Ali is right. One has to live in the present and yet make enough happy memories to last a lifetime.