- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

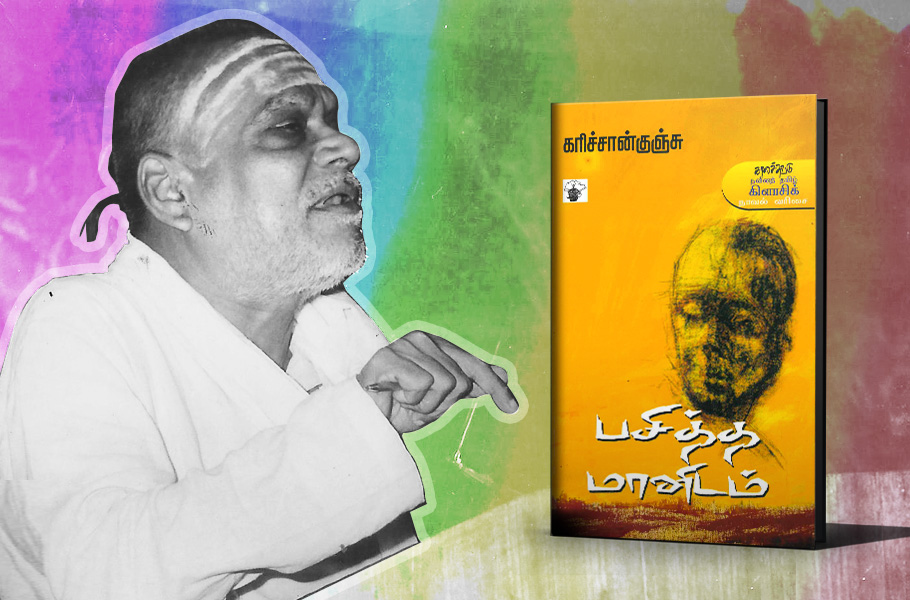

A first gay novel, a poor Tamil Brahmin and an unequal world

For a teacher and Sanskrit scholar in Tamil Nadu of 1970s, talking about sexualities that resist social definitions was not quite the norm. Nor was the temple town of Kumbakonam — otherwise also known as the hub of modern Tamil literature — used to such ‘digressions’. Yet homosexuality found a voice in Karichan Kunju’s writing. Like his celebrated contemporaries...

For a teacher and Sanskrit scholar in Tamil Nadu of 1970s, talking about sexualities that resist social definitions was not quite the norm. Nor was the temple town of Kumbakonam — otherwise also known as the hub of modern Tamil literature — used to such ‘digressions’. Yet homosexuality found a voice in Karichan Kunju’s writing.

Like his celebrated contemporaries from Kumbakonam — such as Na Pichamoorthy, Ku Pa Rajagopalan, Thi Janakiraman, MV Venkatram and Nakulan — D Narayanaswami, who adopted the pseudonym Karichan Kunju, shook the Tamil literary world with his short stories. But it was his only novel, Pasitha Maanidam (Hungry Humanity), which is celebrated as the first modern Tamil novel that dealt with homosexuality. Most importantly, it acknowledged the enduring enigma of sexual desires beyond prudish social and cultural norms — the conflict between sexuality and religiosity in a very ‘Brahmin, Hindu’ world.

Pasitha Maanidam, which turns 40 this year, chronicles the journey of a promising boy, Ganesan, who is sexually abused by older men, and his desire for a fulfilling same-sex relationship later as he grows up into a young man suffering from leprosy.

Even though it touches other aspects of human life — like man’s never ending thirst for power, the power of a debilitating malady — the novel is largely remembered for its take on sexuality.

While his fans and well-wishers are celebrating his birth centenary this year and taking his novel to readers across Tamil Nadu, there were no takers for Kunju’s books back in the day. Most publishers of the time were not ready to publish the novel. This, despite noted writers like Jayakanthan and Thi Janakiraman recommending it to publishers. Finally, Madurai-based Meenakshi Puthaga Nilayam came forward to publish the novel. And, that was how Pasitha Maanidam saw the light of the day in 1978.

“Many say that he wrote this novel because he was in need of money for his daughter’s marriage. Some others say he wanted to write this novel for long. However, what is unfortunate is that those who hail Karichan Kunju for this novel alone are not aware of his short stories, which are richer in content,” says Rani Thilak, a poet who organised Karichan Kunju’s birth celebrations at Kumbakonam recently.

Thilak, who is also collecting and editing some of Karichan Kunju’s short stories, insists that the author’s best work is not Pasitha Maanidam, but Sugavaasi, a novella. “In Pasitha Maanidam, it’s only the protagonist who acknowledges his sexual desires. But it is Sugavaasi that talks about gender expression and same-sex desires in its many different forms.”

However, what most agree with is that it wasn’t easy for Karichan Kunju to talk about gender and lust beyond the binaries in those days. Unlike today, even the so-called liberated class was not open to talking about sexuality and sexual freedom. Something as innocuous as cinema was looked down upon as a medium that would pollute the minds of the young. So, for a teacher to talk and write about sex and sexuality was as rebellious as it could get.

“It was up to the readers. And there was a section of mature readers. Anyone with an eye for good work of literature didn’t find anything wrong or disapproving in Pasitha Maanidam,” says novelist Aravindan. According to him, readers of all age groups — whether 25 or 45 — received the novel with a non-judgemental attitude.

Lost in translation

There was, however, considerable opposition from many others. “Those in the academic circles were not very happy with the work. They treated the novel as a kind of secret treatise. They also believed it would have a negative impact on the ‘behaviour’ of their students,” Aravindan adds.

But even critics awarding favourable reviews to the novel believe that it would be wrong to say that Pasitha Maanidam was about homosexuality alone. It also talks about the dark recesses of human mind where cisgendered men are okay sexually abusing a young boy. The protagonist Ganesan, a survivor of child sexual abuse, is forced to put up with adult depravity because of poverty.

“It is because of the Tamil society’s obsession with sex and people’s reaction to sex as some kind of crime that made this novel to be remembered only for its ‘sexual aspect’. And this is what is unfortunate. It shows our insufficient reading of literature,” an exasperated Aravindan points out.

Another element which could have made the novel attain a cult status was the author himself. Born in a poor Brahmin family, he went on to become a Sanskrit scholar and Tamil teacher. When men of his age were busy arranging their daughters’ wedding, Karichan Kunju was hell-bent on sending his daughters to school. Many close to Karichan Kunju claim that the novel was based on a real-life character.

“In some ways, the novel has autobiographical elements. Like the protagonist of the novel, the author too wandered like a nomad,” says writer and human rights activist A Marx.

When the novel was published, it didn’t create much fuss. It was only after the death of the author (in 1992) that the real importance of Pasitha Maanidam was realised, Marx adds.

“No one spoke about gay relationships so uninhibitedly before Karichan Kunju. More importantly, he acknowledged that homosexuality and same-sex relationships were natural, even before discussions on the subject started in the Tamil society,” says Marx.

Rani Thilak feels now that finally queer literature is being celebrated and there is more awareness about the rights of LGBTQ community, Pasitha Maanidam will shed new light to the existing narrative.

“Publishing the book at a low cost and taking it through readers circles will help the novel reach more and more people, especially the youths,” he says.

But how does the gay community look at the novel? Why does queer literature still struggle to find its rightful place?

The missing voice

“Just like Dalit literature — Dalit writer versus non-Dalit writers writing on Dalit issues — literature written by non-queer writers doesn’t reflect the diverse experience and complexities of queer lives. That’s true about Pasitha Maanidam too,” says author Gireesh.

In 2018, Gireesh published his first book in Tamil, Vidupattavai, under the banner of Queer Chennai Chronicles, a literary forum and independent publishing house. It is also the first-of-its-kind book on gay literature in Tamil.

According to Gireesh, along with the subject, knowledge about queer lives also impacts its reach. “Pasitha Maanidam is yet to reach queer people. In 1950s, writer Ki Rajanarayanan wrote a short story, Gomathi, about queerness. That has reached a lot of queer people here, because of the writing style of the author,” he adds.

Talking about the challenges of publishing queer literature in Tamil and the misrepresentation of queer lives in literature, Gireesh says transpeople are working hard to fight this misrepresentation and make the publishing industry in India more inclusive of queer persons. More and more queer voices need a chance to be heard.

“Earlier, writer Su Samuthiram, a non-queer, wrote a novel about transgender, Vaadaamalli. Later, transwomen like ‘Living Smile’ Vidya and A Revathi wrote autobiographies and poetry collections. That gave great hopes to the queer community. Now, gay men have started to bring out their stories.”

“However, so far there is no homosexual woman writing in Tamil,” rues Gireesh.