- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

A decade's wait for justice: Cancer, depression, death consume Kashmir's mothers

A young Fancy Jan’s life unfurls before her mother Khatija Khan, moment by moment, every day, year after year. It’s been 10 years since Khatija lost her daughter, then 25. But her memories continue to haunt every nook and cranny of their two-storey home in Margarmal Bagh area in Srinagar. No matter how much Khatija tries to avoid these memories, they refuse to go away, taking a heavy...

A young Fancy Jan’s life unfurls before her mother Khatija Khan, moment by moment, every day, year after year. It’s been 10 years since Khatija lost her daughter, then 25. But her memories continue to haunt every nook and cranny of their two-storey home in Margarmal Bagh area in Srinagar.

No matter how much Khatija tries to avoid these memories, they refuse to go away, taking a heavy toll on her body and soul since 2010 — the watershed year when the Valley erupted in raging protests for months.

On April 30, 2010, the Army claimed it had killed three militants in an encounter in Machil sector near the Line of Control. It was later alleged that they had lured local youths, Mohammad Shafi (19), Shahzad (27) and Riyaz Ahmed (21) on the pretext of giving jobs and killed them.

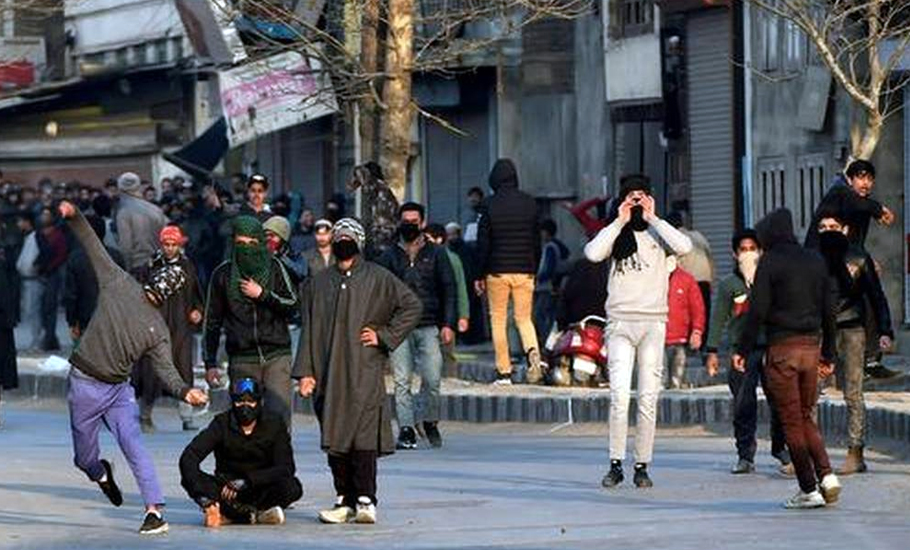

Massive protests erupted across the Valley, demanding justice for the victims and action against the accused, besides the removal of armed forces from Jammu and Kashmir and the repeal of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). (In 2013, five of the six accused army personnel were sentenced to life imprisonment in the encounter case but four years later an army tribunal suspended the sentence and granted them bail in 2017.) By the end of summer that year, 120 civilians, mostly youngsters, were killed across Kashmir. Fancy Jan was one among them.

“On that unfortunate day,” Khatija recalls, “my daughter was drawing the curtains of her room to stop the bitter tear-gas smoke from flooding our home and choke us inside.” On the street passing through the neighbourhood, protests were going on.

“Amid the commotion and confrontation outside, my daughter suddenly cried out, ‘Mouji, Mehaey Lagawiekh Goe’l” (Mother, they shot me).” Even before Khatija would react, the bullet tore through Fancy Jan’s body. It was 2:30 pm on July 6,” 2010, she remembers.

“My daughter was brave and independent. She made crewel bedsheets to support us,” Khatija recalls. Apart from struggling for means, she and her family have been vainly chasing justice.

“Now, I am no longer in a position to continue my justice campaign,” she laments. Years of trauma and crying have left her partially blind. To make things worse, Khatija recently discovered she has cancer.

“I have to spend around ₹30,000 every month for my treatment, which my husband, a street vendor and daily-wager son can’t afford. In the name of compensation, we are still awaiting a promised government job,” she laments.

‘Lost Companion’

A few days before Khatija lost Fancy, another mother in Noor Bagh area, Dilshada Begum had lost her son, Rafiq Ahmad Bangroo. Rafiq means companion. On that seething June afternoon, Rafiq, a Kashmiri shawl artisan, left home with his friends and never returned. He was killed near his home when armed forces went on a rampage to scuttle a protest.

“I lost myself the day he was killed. Nobody can imagine living in this world without their child,” Dilshada, a woebegone mother says.

Two years later her husband passed away and she was diagnosed with diabetes and heart ailment. To console her, Dilshada picked up an odd routine after her son’s departure. She would frequent the families of other “martyrs” to cry her heart out. She made rounds of her son’s grave near her home and sang dirges for him.

“Everything I liked hurts now,” she says.

The family has hidden all the belongings of Rafiq, as even a glance at his clothes, photograph or even a utensil triggers a violently emotional episode in Dilshada. Sadness and the pent up anger have made her edgy over the years. She believes that the ‘criminals’ won’t be punished ever. The family was planning Rafiq’s marriage when he was killed. Now that he is not here, Dilshada has named her grandson Rafiq. She calls him a hundred times every day. Calling his name soothes her and acts like a therapy.

Like Dilshada’s life, the human cost of the protracted conflict in Kashmir is immense. Killings of civilians have become a routine in the past three decades. The slain leave behind a trail of misery and pain in which the women have been the worst sufferers.

Kashmir in a way is a saga of pain and hopelessness of these struggling mothers. Their stories bear similar tragic losses. They want to find out the truth and are waiting endlessly for a closure. The killings are like an open wound for the families and every hour of delay in justice adds to the trauma.

‘Died to meet her son’

Akhtara Banu, another mother, suffered her son’s loss silently in a small house in Narwara area plagued by poverty and pathos till she passed away in 2019. Her son Anees, 17, was killed in 2010, near his house, when a patrolling party of armed forces opened fire at him. Neighbours say he was standing near an electricity pole and was targeted directly.

In a cramped kitchen, her daughter, Rukayya narrates the decade-long tragedy the family has been living through. After Anees’s killing, Banu would lament for long hours with herself inside her room. She often smelled his clothes and cried for long hours. She even stopped preparing meals and left all other tasks to her daughter.

“She lived in acute pain,” Rukayya says. “My brother’s brutal killing badly depressed her. She developed many health ailments, like diabetes, kidney stones, thyroid and heart issues.”

Justice still eludes the family.

But years before her son’s killing reduced her to a bundle of nerves, Banu had arrived in Kashmir as a young and happy bride from Kolkata, married to a Kashmiri shawl seller.

“Our mother was a fun-loving person. She liked to do shopping, wear nice clothes and enjoyed every bit of life even with all the constraints,” says Rukayya. But Anees’s killing changed her forever and she left this world as a different person. She rarely stepped out of her home in the nine years since.

Before his killing, Anees was nurturing a dream of studying MBA outside Kashmir. “He was an intelligent and hardworking boy,” Rukayya says.

Once in Class 7, his father put him on a detention assignment with a local barbeque vendor after he fought with some boys in the neighbourhood. Anees was calm and focused. He not only learned to make tasty barbecues but earned ₹20,000 and gave it to his father, she recalls.

“Every morning, my mother used to wake up narrating different dreams about Anees. Sometimes she would see him as a groom and sometimes as an officer in a big corporate office,” Rukayya says. However, one dream of seeing him smiling and strolling in the Valley of flowers was regular for nine years.

“She knew that her son was fired on the leg and the poison of that fire had reached his heart and killed him. Some eyewitnesses who came to our house said that he was thrashed badly by the forces after being shot,” says Rukayya.

These thoughts and trauma, Rukayya says, took a toll on her mother’s heart last year. “She desperately wanted to meet her son.”

Endless wait for justice

The year 2010 has around 120 similar stories and since then the graph has only increased. According to J&K Coalition of Civil Societies reports and that of few other organisations, around 945 civilians have been killed since 2010 in J&K. Justice eludes them all.

To investigate the 2010 killing, then chief minister of undivided Jammu and Kashmir Omar Abdullah had constituted a one-man commission of Justice (retd) ML Koul in 2014. The commission submitted its report to the government of People’s Democratic Party-BJP led by Mehbooba Mufti in December 2016.

The report was never made public officially but some of the findings leaked in the media suggested that it had indicted the government forces for “firing upon demonstrators without magisterial orders” and “accused them of using disproportionate force on protesters”. The recommendations were never implemented.

Activists have cried foul over the inaction, saying the Koul commission was entrusted with several aspects of the killings and not just paying ex-gratia relief to the families of the victims.

The Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society and Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons in Annual Human Rights Review in 2018 had termed the inaction “an example of glaring structural impunity enjoyed by the armed forces”.

Besides noting that the Koul Commission report was not made public, it also pointed to the fact that the report was not made available to the families of the victims, who they said, had termed it a “wasted exercise, aimed to deny justice to the victims”.

The report also notes that ordering probes and instituting commissions after several similar extra-judicial killings by the forces and human rights violations have become a customary practice with the government that has led to no concrete results and were “farcical” to the civilian population.

Between 2008 and 2018, 107 enquiries have been ordered by the Jammu and Kashmir government, but most have not reached its logical conclusion.

‘Friends in Pain’

The Koul Commission had also recommended a CBI investigation into the killing of Tufail Matoo, a teenager, who became the first casualty in 2010 that triggered a series of killings.

Tufail’s family is also fighting for justice. His father Muhammad Ashraf Mattoo has a single mission of fighting for justice for his son. A few hundred meters from his residence in Rainawari, Ashraf has found a companion in grief and suffering in Farooq Ahmad, whose 13- year-old son Wamiq Farooq, was also killed in similar circumstances at the same place, in January 2010.

Farooq and Ashraf, despite living in the same area for over four decades, were strangers till 2010. The killings of their sons and the unending grief brought them together. They are often seen together, taking long strolls in the alleys of Rainawari, probably remembering their children and giving each other the courage to not give up.