- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

100 years on, what makes Nadars a success story in banking

Many would know Tamilnad Mercantile Bank as a bank that caters to businesses, especially small and medium ones, started by Nadar community.

“Though the Shanars rank as a caste with the lower classes, and though the greater number of them earn their daily bread by their daily labour, pauperism is almost unknown amongst them. Of the great majority it may be said, that they are equally removed from the temptations of poverty and riches, equally removed from the superficial polish and subtle rationalism of the higher caste,...

“Though the Shanars rank as a caste with the lower classes, and though the greater number of them earn their daily bread by their daily labour, pauperism is almost unknown amongst them. Of the great majority it may be said, that they are equally removed from the temptations of poverty and riches, equally removed from the superficial polish and subtle rationalism of the higher caste, and from the filthy habits and almost hopeless degradation of the agricultural slaves,” writes Christian missionary and Tamil scholar Robert Caldwell in his book, ‘Lectures on the Tinnevelly Missions, published in 1857.

Despite his seemingly dismissive tone, Caldwell wasn’t quite off the mark. For, it is believed that the Shanars, who later came to be known as Nadars, were able to keep poverty at bay through sheer hard work.

The main occupation of this community back in the day involved climbing palmyra trees and tapping toddy.

In the first census carried out in 1881, Shanars were classified as a lower caste. Because of this, throughout the 19th century and until the first half of the 20th century, they were subjected to different forms of untouchability. For instance, they were not allowed to draw water from the wells, not allowed to walk on the main road, and not allowed to milk the cows.

In 1897, a group of Shanars entered the Meenakshi Sundareswarar temple in Kamudhi in present-day Ramanathapuram district. This rebellious step prompted the then Ramnad king M Baskara Sethupathi to file a case against Shanars. The case was first heard in the Madurai district court, then in the Madras High Court and then in Privy Council in London which finally ordered that Shanars have no rights to enter the temple.

It was during those turbulent times that Shanars slowly changed their occupation from tree climbing to other jobs such as selling groceries. Their endogamous practice further helped them stay and work together in synergy. Some of the elderly members would often get together once in a while and discuss the community’s development.

It was during one such meeting in 1920 that the seed to start a bank was first sown. Something that would primarily help the community. Accordingly, in 1921 a bank was opened. A century later, that same bank has become synonymous with Nadars and their successful banking skills.

From palmyra to pettai

The Nadars, original inhabitants of Tirunelveli, Thoothukudi, Virudhunagar and Kanyakumari districts, collectively lived in South Travancore before the state’s reorganisation.

Historically, the Shanars were cultivators of palmyra trees who would then produce jaggery and toddy out of it. This association with toddy may have been a reason why Shanars were considered untouchables since consuming toddy was considered a kind of grave sin in those days. However, according to one study, Palmyra tree and its role in the development of Nadar community of Kanyakumari district by T Thanga Regini, although they were associated with toddy, Nadars seldom consumed it.

History is replete with examples of upper class privilege subjecting the Shanars to multiple forms of discrimination. For instance, women of the community were not allowed to cover their breasts, and were taxed heavily, according to the size of their breasts, if they did so. Although the Shanars considered themselves somewhat-superior than the Sudras (in the caste hierarchy), they were mostly treated as equal to Sudras.

Caldwell records this difference well. “In some respects the position of the Shanar in the scale of caste is peculiar. Their abstinence from spirituous liquors and from beef, and the circumstance that their widows are not allowed to marry again, connect them with the Sudra group of castes.

“On the other hand, they are not allowed, as all Sudras are, to enter the temples; and where old native usages still prevail, they are not allowed even to enter the courts of justice, but are obliged to offer their prayers to the gods and their complaints to the magistrates outside, and their women, like those of the castes still lower, are obliged to go uncovered from the waist upwards. These circumstances connect them with the group of castes inferior to the Sudras; but if they must be classed with that group, they are undoubtedly to be regarded as forming the highest division of it“, he writes.

The Shanars struggled with caste identity for a long time and then their fate turned, or one could say they changed their fate, with the arrival of the British. On one side, the Christian missionaries extended their support to the community. The first recorded conversion in Tirunelveli goes back to 1789. By 1849, about 40,000 Shanars were converted.

On the other hand, different kinds of endeavours by the British enabled the Shanars to try their hand at different jobs, such as building roads, working in coffee plantations in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and others in the grocery trade.

However, those involved in the grocery trade often got robbed. To avoid this, the Shanars started to set up ‘pettai’ (a place to rest which also has fortified storage buildings). To manage these ‘pettais’, they created a funding system, which became a starting point for launching a bank in the future.

Magamai fund, a saviour

These ‘pettais’ could be found in every village where the Shanars used to do business. Today, such villages have been transformed into small or big towns but they retained their names and thereby stand as a marker of a bygone era.

Over time, the Shanars realised that they needed money to maintain these pettais. That is when they created a financial institution called ‘Nadar Magamai Fund’. It was more or less similar to the service tax that’s in practice today.

Every trader who would use the services of a pettai was required to pay a small percentage of their revenue to the Magamai Fund. The vehicles which crossed a particular pettai were also required to pay a fee.

“It was in Virudhunagar where the system started first. In those days, it was just a handful of rice, collected as ‘fund’. The ‘pettai’ leaders would sell those rice grains and convert that into money. In some other areas, instead of rice they used to pay in the form of cotton, tamarind, millets, etc. The payment in the form of money came into practice much later,” says G Karikolraj, general secretary, Nadar Mahajana Sangam.

Today, the fund is called ‘subscription’ in urban areas. In rural areas, it is still known as ‘Magamai’ fund.

According to Karikolraj, the word ‘magamai’ is more or less similar to ‘zakat’ (Islamic charity).

After a while, he adds, the Magamai Fund grew bigger and bigger. “The Shanars in every pettai would get together once a month and discuss how to utilise the funds in a better way to benefit the entire community.”

Having realised the importance of education, the Shanars used the Magamai Fund to build a Kshatriya Vidya Sala (KVS school) in Virudhunagar in 1885. Former Tamil Nadu chief minister and Congress leader K Kamaraj studied in this school, which has a long list of brilliant students.

Once the Shanars made considerable progress, both economically and educationally, they wanted political representation. Back in the day, every community needed a separate association to represent them. The absence of one wouldn’t bode well. So the community members formed the ‘Nadar Mahajana Sangam’,headed by Rathinasamy Nadar, in 1910. This association went on to become the base for ‘Nadar bank’.

A community asset

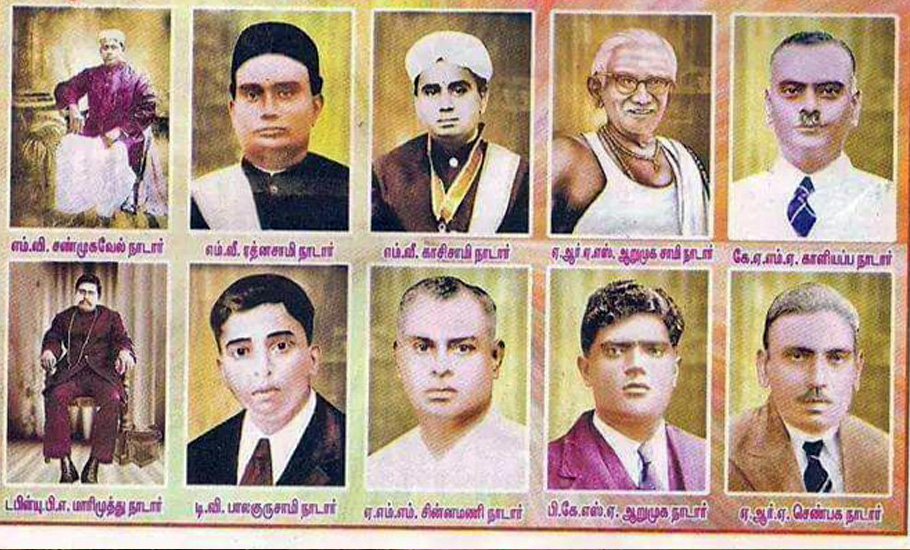

While Rathinasamy Nadar came up with the idea of setting up a bank for Shanars, a resolution was passed in this regard at a meeting held at Thoothukkudi in early 1920. On May 11, 1921, ‘The Nadar Bank Limited’ was launched with an investment of Rs 5 lakh. The first bank was opened at Aanaa Maavannaa building on South Raja street in Thoothukudi.

In the same year, the community name—Shanar—was changed to a more respectable Nadar.

It was a result of the efforts of Rathinasamy Nadar and his petitions sent to British officials between 1910 and 1921, demanding to legally change the name Shanar to Nadar.

So, Nadars had another reason—exactly a century ago—to celebrate that year.

In 1922, the bank had a deposit of Rs 21,010. Today, it stands at Rs 40,970.42 crore.

Similar to the deposits, the profit figures also look impressive. In 1922, it made a profit of Rs 6,984. In 2020-21, the profit stands at Rs 603.3 crore.

The opening of its branches in different districts is one of the reasons for its success. In 1928, a branch was opened in Virudhunagar. That was followed by a branch in Madurai in 1931 and another in Dindigul district in 1933. In 1934, a branch was opened in Chennai and one more in Theni district in 1937. A branch was even opened in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

In 1947, the bank had only five branches. By 1970, it had 11. In 1983, it crossed the 100 mark. In 2000, it had 160 branches. Right now, it has 509 branches.

In 1962, the Nadar Bank was rechristened to Tamilnad Mercantile Bank to widen its reach.

Fissures in governing the bank

All seemed to be going well until a fissure in the mid-90s. “There are two Nadar groups which have equal powers. One is Nadars from Thoothukudi, and the other from Sivakasi and Virudhunagar. The bank officials from these two groups at the highest level fought among themselves over ownership. They tried to convert the bank into a single family’s asset. But both the groups failed and the Sivakasi-Virudhunagar group sold its shares to Essar Group, which was in no way related to Nadars,” says Karikolraj.

“The Nadars from other districts—such as Tirunelveli and Madurai—formed a group called ‘Nadar Mahajana Bank Retrieval Forum’ and started demanding that the bank sells its shares only within the community,” he says.

The forum knocked the doors of the Supreme Court and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as well.

“There is a rule as per bank bylaws. That is ‘this bank will work for the upliftment of the Nadars’. Using that, the forum won the case. The RBI too refused to register the shares under Essars name,” Karikolraj adds.

After a series of twists and turns, part of the disputed shares eventually landed among Tamils in Mauritius. “In the last 30 years, we have managed to retrieve 40 percent of the shares. We are still fighting to get back the remaining shares,” adds Karikolraj.

While a lot of water has flown down the Thamirabarani river, one reason the organisation survived all these years, according to Karikolraj, is its employees.

“The bank still gives first priority to Nadars. Almost 90 percent of its employees are Nadars. Each and every employee is focused only on work. They never got into politics and that’s why the bank survived such fights.”

Continuing the tradition

While the Tamilnad Mercantile Bank continues its tradition, many question its existence as a ‘one-time achievement’. Questions have often been raised as to why there is no other Nadar bank.

Business journalist Saravanan has an answer.

“The answer is very simple. The community members may have felt that another bank would have become a competitor to TMB.”

According to another business writer who closely followed the Nadar community for many years, there is a possibility that business activities couldn’t thrive as the freedom struggle intensified between 1920s and 1940s. “So, they may not have felt the need for another bank.”

“After 1947, the government itself started launching its own banks and the Nadars may have thought that opening a new bank would be redundant,” he adds.

But Karikolraj believes otherwise. Another bank from Nadar community is coming up gradually.

“In 2010, during the centenary celebrations of Nadar Mahajana Sangam, we launched ‘Pandianad Finance Company Limited’. It’s been five years now.”

When it completes 10 years, he proudly adds, it will be recognised as a bank.