Whatever happened to the Chennai #MeToo movement?

If the Supreme Court was rocked by sexual harassment allegations recently, just a few months ago, the performing arts community in Chennai went through a storm. Tamil film personalities like lyricist Vairamuthu, apart from Radha Ravi, John Vijay, Susi Ganesan, and singer Karthik were alleged to be some of the perpetrators.

The conservative, tradition-upholding world of Carnatic music was hit too. Complaints started pouring forth, nearly all anonymously, against some of the biggest stars: Chitravina Ravikiran, Sasikiran, OS Thyagarajan and so on. On Facebook, Twitter and in public hearings, the complaints were voiced, anonymously by current or former students of the musicians. The hallowed ‘guru-sishya’ relationship that till today remains the predominant teaching method in Carnatic music in Chennai was under question.

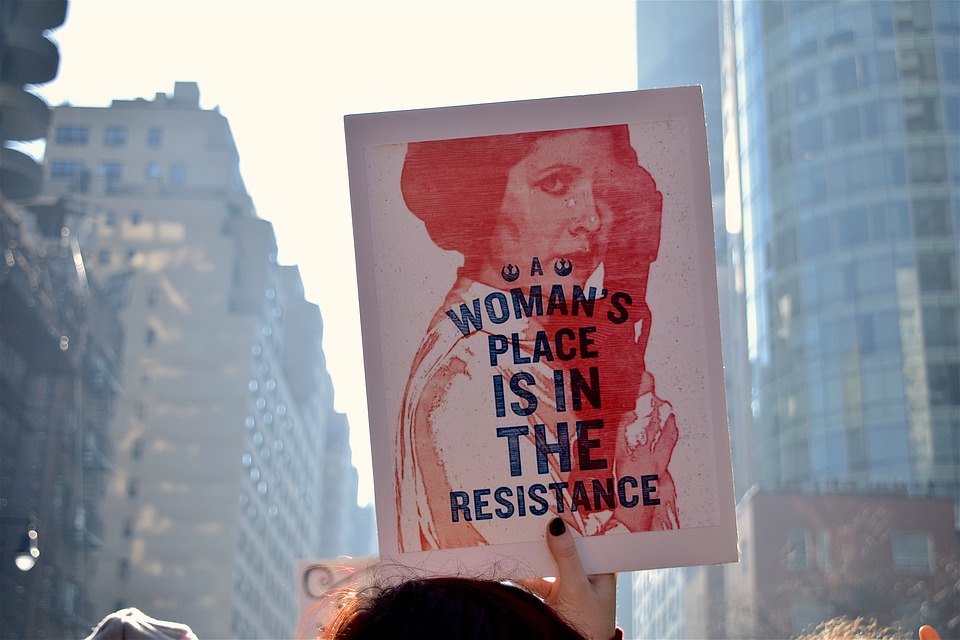

Yet, within a few months, MeToo receded from the public sphere. It had been a moment, not a movement that many described it to be. No process has unfolded against the alleged perpetrators. The activists spearheading the movement have gone quiet, too.

The activists now say women made major gains. There is increased awareness against sexual harassment in all walks of life, and a silent change has already happened. It is only a matter of time before major changes happen.

The musicians, however, say it was a nightmarish time for them. They couldn’t address the complaints since they were anonymous and their reputations had been slurred. Careers built over a lifetime were suddenly in tatters.

Singer Chinmayi Sripada who took on film lyricist Vairamuthu with her own story of harassment invited support and severe backlash, at the same time. Chinmayi is now campaigning against the clean chit handed out to Gogoi.

Aftermath of #MeToo

Radhika Ganesh of the collective ‘Ek Potlee Ret Ki’ or ‘Oru Kani Nilam’, who brought about a public discourse in October last year with women sharing their real life stories of harassment with a panel of experts from various fields, says that one positive outcome of the movement has been the opening of the space for dialogues.

It has been a crescendo, with women from middle class families in cities showing a moment of solidarity and speaking up about what they had undergone or standing up for women who have – Radhika Ganesh, Ek Potlee Ret Ki

She said, “It has been a crescendo with women from middle class families in cities showing a moment of solidarity and speaking up about what they had undergone or standing up for women who have.” She points outs that women have been collectivising to set up internal complaints committees following the Visakha guidelines.

She says that the challenge remains about the due process followed after the accusations, as in the case of the CJI where the procedure followed has been questioned.

A procedure in place for arts

A major reason for the movement to die down has been that no one of those who named classical music artistes has come forward to lodge a complaint with the internal complaints committee (ICC) formed by the Federation of City Sabhas in Chennai last year. Radhika says that it is due to the fear of the powerful. “I have spoken to so many who worry that their careers will end of they go to the ICC, as most names on the list are big / senior artists. And as everywhere, here too, the perpetrators enjoy the company and patronage of the powerful and those at the helm. This is the main reason. Apart form this, stigma and public victim blaming is also causing great anxiety,” she explained.

Dancer Swarnamalya Ganesh has been among a group working towards setting up a procedure to facilitate an environment congenial to encourage complaints. She said, “We have been taking a bit of time to ensure that it is a loophole-free system. The way we are trying to frame it is that it permeates into the classroom of an art programme, like a workspace. The music sabha is just a place for culmination of arts. We are looking at personal code of conduct and getting an MOU signed by those who are willing to teach and learn. It will at least hold them responsible for their own behaviour. At the same time, this will be sensitive and uphold the sacrosanct relationship between the teacher and disciple.”

N Murali, president, The Music Academy, one of the most illustrious performance venues for classical music and dance, observes that the bigger challenge is the absence of a legal standing for joint committees, a structure suggested by some activists like Radhika, to take up such complaints . He said, “The internal complaints committee is already in place. The challenge is it cannot take up cases that took place outside the venue. “

He added that the sabha had dropped artistes who were named in the movement last year to uphold the probity of the academy. “We have not blacklisted them forever. We cannot hold them guilty based on complaints alone.”

Who were the victims?

R Ramesh, a mridangam artiste, whose name featured in the list says that a complaint alone cannot be assumed as truth. The artist added that he is still clueless as to who the complainant could have been. He was accused to have molested a young boy. He said, “The victim here is me and I don’t even stand a chance to prove that because complaints were being admitted as the ultimate truth.”

I have lost my mother and my father is bedridden, after the unfortunate event. The only support has been my family and friends, who have stood by me – R Ramesh, mridangam artiste, whose name featured in the list of sexual predators during the #MeToo movement

He says that the accusation has killed his reputation and career, with him suffering both physically and mentally. “I have lost my mother and my father is bedridden, after the unfortunate event. The only support has been my family and friends, who have stood by me.”

The day the allegations against him were made public, Chitravina Ravikiran, vocalist and instrumentalist, took to the social media to deny them, saying that he has been working towards eradicating such problems within the space of arts. He wrote on his Facebook account. “In fact, I have been fighting this rampant (though largely ignored) evil for nearly 25 years in my own small ways including: Counselling disciples who face harassment in the art world as well as those traumatised by predators on public transport and lewd exhibitionists on lonely streets. Urging them to form stronger collective fronts amongst their friends to strongly counter this evil. Encouraging them to discuss it with parents/family than suppress it for years. Brainstorming with a few about organising special socio-cultural events to increase awareness regarding this. At the same time, every fair person must earnestly ensure that a small section of people with ulterior motives do not abuse the noble spirit of the #MeToo movement to settle personal vendettas under the protection of anonymity or under the guise of socio-political activism.”

The discourse should continue

Radhika talks about how the movement has triggered an active response from young women bureaucrats who have sent out a strong message to society. She added, “In Cuddalore, we have had a sub collector encouraging women to come forward to report instances of harassment in any industry. That makes a huge difference.”

Saundarya Rajesh, founder-president of Avtar Group, who works towards diversity and inclusion in workplace, observes that while there has been awareness, it is restricted to metros. She said, “But all of this – this awareness we are talking about is primarily in the metros, in the big corporates, but where previously there was a laissez-faire attitude, there is greater awareness and sensitization. in the MSME sector, in the small cities and towns, the Indian woman still suffers a lot of challenges. No one has heard of MeToo in that small coastal town of Tamil Nadu and the owner-manager still behaves creepily to his employee. If we need to create real change, real momentum of change, we need to go deeper into the underbelly of India.”

Radhika agrees that the collective public memory has relegated the movement to the corners over a period of time. She said, “It is the same thing that happened with the Nirbhaya case, a case of public driven news cycle. It is also not fair to examine the success of it on a case to case basis.”

Swarnamalya reckons that a problem as complex as this and that is deep seated in society and across, requires not just a climatic change, but also needs individual onus and responsibility and consciousness. “It is going to take a long time for change to come into effect. To get a safe environment is a long road. We are not just talking about women safety here, and there have been men too. It is just that women are more in number,” she says.