TN night ban on road via tiger reserve raises more questions than answers

The forest officials’ claims on road kills of animals have made the daily life of people living around Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve miserable

The Madras High Court’s recent directive asking the Tamil Nadu government to effectively implement a night ban on the movement of vehicles on a stretch of NH 948, which passes through Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, comes as a good news for wildlife enthusiasts and conservationists. However, the ban, if implemented to the hilt, is likely to impact the daily lives of residents in and around the tiger reserve in Erode district.

The HC decision on March 2 talks about better control over the movement of vehicles on the 29-km stretch of national highway from Bannari to Karapallam. The road runs through Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve, which has been recently conferred with the prestigious TX2 award for doubling the number of tigers.

Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve is the first major reserve in the state which does not have an alternate road route. The existing night ban on night movement of vehicles in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve stretch is just an expansion of similar restrictions in Bandipur Tiger Reserve.

The problem area

Erode district is one of the main cities of Kongu region. Though it is not cosmopolitan like Coimbatore, the nearest big city, a large part of agricultural products like turmeric, sugarcane, cotton and paddy are supplied from Erode. The national highway is the only one that connects Bengaluru with Coimbatore and is used by the residents and farmers for their day-to-day activities like going to schools and colleges, hospitals, courts and for selling their farm produce.

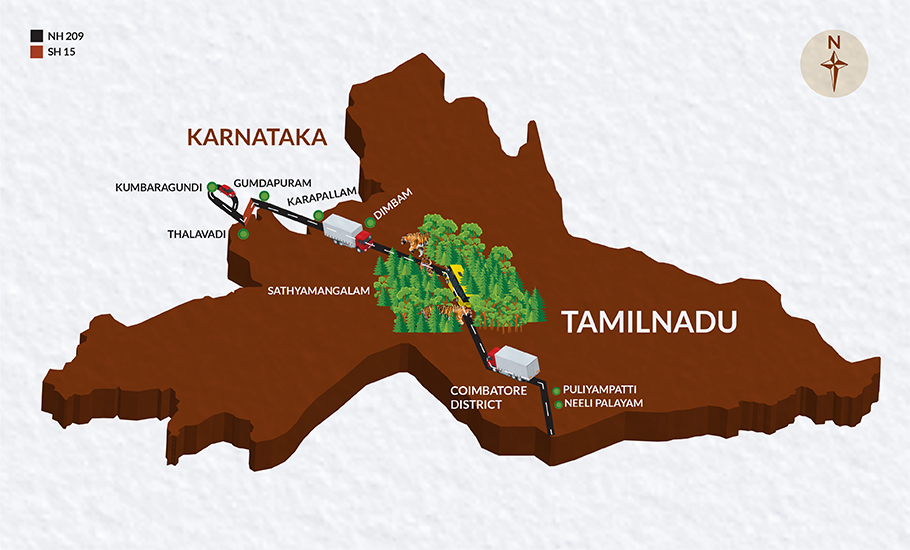

The road bisects the Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve. It enters the reserve at Bannari in Sathyamangalam forest division and traverses inside the reserve for a distance of 29 kms (17 km in Sathyamangalam division and 12 km in Hasanur division) before reaching Karapallam check post, the last place on Tamil Nadu border, to enter Biligiri Ranganatha Temple tiger reserve in Chamarajanagar district of Karnataka.

The road starts from Kovilpalayam in Coimbatore district and runs through Annur, Puliyampatti, Sathyamangalam, Bannari, Dhimbam Ghat, Hasanur, Chamrajanagara, Kollegal, Malavalli, Halaguru, Sathanur, Shivanahalli and Kanakapura before reaching Bengaluru. Hence, the Bannari-Karapallam stretch is also known as ‘Dhimbam Ghat’.

A curse in disguise

“The taluk has 10 panchayats and more than one lakh people live in this region. To reach or to come out of the region, one needs to take a detour via Karnataka and enter Tamil Nadu,” said Mohankumar, a CPI cadre and a tribal rights activist in Erode.

If the residents of Thalavadi block, located in the hills, want to access the nearby town on plains like Erode or Sathyamangalam, they need to start as early as 6 am so that they can reach their destination by 9 am. “The stretch of road has 27 hairpin bends. In 2019, following claims that many wild animals are dying in road accidents, the then collector of Erode, C Kathiravan, ordered a ban on vehicular movement on this part of road at night. While the objective was good, it turned out to be a curse for the locals. The vehicular movement was stopped from 6 pm to 6 am. Because of that, on any given day, nearly 100 vehicles, including heavy vehicles like lorries laden with sugarcane, coconuts and other agricultural produce, need to be stopped at the tollgate near Bannari check post till sun rise. The road opens in the morning with a huge traffic jam. The people of Thalavadi need 4 to 5 hours to complete the travel, which means waste of a whole day,” said Mohankumar, a resident.

Needless to say, students, patients and people engaged in court matters are the worst affected. Because of traffic jams, school children have to walk 4 kms up and down every day. Farmers struggle to sell their produce in 144 villages surrounding Thalavadi region, Mohankumar added.

Lack of consensus on number of road kills

The 2019 order of the Erode collector to implement night ban was passed following a district road safety committee meeting held in October 2018. Besides vehicular accidents, the order was also aimed at reducing road kills of wild animals.

An RTI reply received from the field director office of Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve states that between 2012 and 2021 only 40 road kills happened on the road from Bannari to Karapallam.

“Out of 40 road kills, only 10 happened at night (6 pm to 6 am) till 2019 and a lone accident was reported in 2020. The remaining accidents happened during the day. The Madras High Court has wrongly observed that there were 152 road kills between 2012 and 2021. Within the forest department there is no consensus on the data,” said Mohankumar.

When asked about the discrepancies in the data, Shekhar Kumar Niraj, chief conservator of forests and chief wildlife warden of Tamil Nadu, said the deaths of wildlife animals are definitely more than 100. “But death is not the only issue. Movement of vehicles at night causes several disturbances to animals. They are unable to cross over when the road is congested. Due to continuous movement on the stretch their genetic dispersion may also get affected. We should also look into these issues. The deaths are only the last part of the problem,” he said.

‘No systematic study on vehicular movement’

The petitions filed in the Madras High Court claimed that nearly 6,000 vehicles plied through the tiger reserve every day before the night ban. When The Federal contacted road transport officials in Erode, they said the claim is wrong. “The number of vehicles plying on this stretch of the National Highway would not be more than 1,000 to 1,500 on any day. The forest officials know the exact number of vehicles plying on that road because they are the ones who collect tolls from vehicle owners. However, they are hiding the real numbers,” an official said.

Mohankumar said that even if the forest department’s claim is true on the number of vehicles passing through the road, it means for every minute there must be 4 to 5 vehicles plying on the road. “But such a big number of vehicles cannot ply on this portion of the road in a minute that too at a fast pace, which means they would be required to move slowly. Only 10 kms of the stretch – 3 kms from Bannari to the foothills of Dhimbam and 7 kms from Dhimbam peak to Karapallam – is on the plain, where the vehicles can actually move fast. The night ban is like punishing 5,800 vehicle owners for the road kills occurring due to accidents caused by 200 vehicles. This is not fair,” he added.

‘Night ban definitely works’

This is not the first time a road stretch in Tamil Nadu has been restricted for vehicular movement at night. It has a precedent. In August 2009, the Karnataka government imposed a night ban on National Highway-766 that connects Kerala’s Wayanad and Karnataka’s Mysuru. This road runs through Bandipur Tiger Reserve (BTR). It was claimed that between 2004 and 2007, 215 wild animals were run over by vehicles. The Karnataka government then claimed that in a span of 30 minutes 44 vehicles were plying on the 19 km long road.

“The night ban impacted the people in Wayanad district and protests erupted. The authorities then found out two alternatives. But in our case, there is no such alternative. Not only the farmers of Tamil Nadu, but also the farmers from Karnataka are using this road to reach Mettupalayam, one of the biggest market for both agricultural and horticultural produces in south India. Perishable goods must be taken to the market within a stipulated time. When the government restricts vehicular movement, it results in heavy traffic jam for the next 12 hours. That brings losses to the farmers,” said Kannaiyan, a farmer in Thalavadi.

In order to ease the traffic, the National Highways Authority of India in 2010 decided to expand a part of the National Highway 948 into four lane between Dindigul – Coimbatore – Sathyamangalam and the construction work started in 2020 for a cost of nearly Rs 650 crores. However, the permission for paving the road along the stretch between Coimbatore – Sathyamangalam is pending with the forest department, since the stretch will run through Velamundi Reserve Forest, a part of which comes under Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve.

“On one hand you widen roads to ease congestion and on the other hand you create traffic jams by invoking night ban, which is not the only solution to prevent roadkill. Instead, the forest department should consider alternatives like having more speed breakers, imposing fines on heavy vehicles that violate the weight rule, putting CCTV cameras to monitor, punish overspeeding and efficient patrolling should be considered,” said Mohankumar.

K Kalidasan, president, Osai environmental organisation, however, said that studies prove that the night ban works. “Most of the animals found in the Sathyamangalam Tiger Reserve are nocturnals. Many small and less charismatic species are killed by the vehicular movement and aren’t counted in the roadkill data,” he said.

When asked about a viable alternative, Shekhar Kumar Niraj, chief conservator of forest, Tamil Nadu, said that as a result of the ban, heavy vehicle movement through the reserve has been reduced to 50 percent. The rest were diverted through Salem-Dharmapuri Highway.

As of now, the Madras High Court has allowed vehicles to ply at night only for medical emergencies. It also ordered the government to fix CCTV cameras every 5 kms along the stretch. Meanwhile, the people of Sathyamangalam have filed a writ to revoke the night ban.