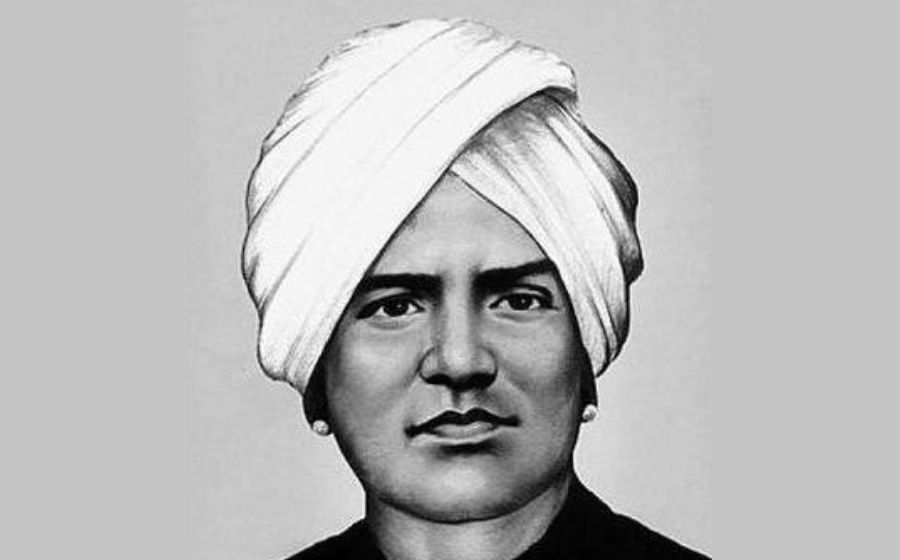

Iyothee Thass: The man who gave Tamils a new identity

Around 110 years ago, the plague pandemic and a severe famine had struck India. Hospitals were filled with patients. People neither had food nor clean water. They were dying of both the disease and hunger, and were forced to migrate to other towns.

While most magazines and newspapers were reporting on the day-to-day updates about the pandemic, there was one magazine that published stories about the sections vulnerable not only to Plague, but also another pandemic called caste. Along with other updates, it told the people the stories of the subaltern — the Dalits. The magazine was Tamilan.

Founded by C Iyothee Thass, the magazine carried an article in its issue, dated October 23, 1912, about the famine that had permeated Tamil Nadu.

“Leaders spoke of freedom, swadeshi and patriotism and gathered masses of people. They collected money from every street. But when people are suffering the famine, no leader has come to wipe their tears. Their patriotism relies on selfishness. Those who do not pay attention to the poor during the famine will not even think of people in their dreams,” wrote Iyothee Thass, who was the editor of the magazine.

It is surprising to see these words continuing to reverberate even today. At the same time, it is shocking to know that the state has forgotten a prolific visionary.

Birth of an icon

Born as Kathavarayan on May 20, 1845, in Royapettah, Chennai, Iyothee Thass belonged to a family of practitioners of traditional Siddha medicine. His father Kanthappan worked as a servant to British officer Francis Whyte Ellis, who was a scholar of Tamil and Sanskrit.

It is interesting to note that when Ellis tried to collect ancient Tamil texts to publish them into books, it was Kanthappan who gave Thirukkural and Naaladiyaar, written on palm leaves to Ellis. Kathavarayan’s family had preserved ancient manuscripts and he was introduced to many ancient literature at a young age.

He was taught to read and write at a thinnai pallikkoodam (a verandah school) run by Kalathi V Iyothee Thass Kaviraja Pandithar. Having a huge respect for his teacher, Kathavarayan later changed his name to Iyothee Thass.

Later, his family moved to The Nilgiris, where Thass practised Siddha medicine and founded the Advaidananda Sabha in 1870. The two major objectives of the Sabha were opposing the proselytisation of Christian missionaries and fighting the caste system.

In 1891, he founded the Dravida Mahajana Sabha and organised its first conference in Ooty, where its members passed a resolution seeking a law to punish those who called the Dalits as Pariahs.

Related News: Not only COVID cases, caste atrocities too spike in TN amid lockdown

After spending 17 years in The Nilgiris, Thass returned to Chennai in 1893. In 1907, he founded a weekly magazine, named Oru Paisa Tamilan, which was rechristened a year later as Tamilan.

Through this magazine, Thass had contributed to subjects like caste, language and religion. He wrote many columns in the magazine that were later published as books. The magazine was successful until Thass’s death on May 5, 1914.

“His book Indirar Desa Sarithiram (History of India) can be classified as the first book of the subaltern history of India,” says D Ravikumar, Lok Sabha member from Villupuram, in his piece about Thass in The Indian Express.

The icon’s 175th birth anniversary is being celebrated by the Dalits across the state on n Wednesday (May 20).

The forgotten leader

In 1999, researcher G Aloysius brought out the writings of Iyothee Thass under the title K Iyothee Thassar Sinthanaigal (Thoughts of Iyothee Thass). By then, 154 years had passed. Until then, the was hardly any discussion about Thass among intellectuals and anti-caste activists. Thass had been forgotten for almost a century and a half.

“Only recently, the practice of quoting someone while writing history has come into place. No researcher has researched completely about the history of the Tamil society. That’s how we missed Thass. Even before Thass, there was another thinker, named Venkatachala Naicker. We need to study about such personalities more,” said Aloysius.

Interestingly, Aloysius came to know about Thass through one of the articles written by researchers SV Rajadurai and V Geetha in the early 90s. The article kindled the interest of Aloysius to know more about Thass. That was how he started to collect the copies of Tamilan. The research resulted in bringing out writings of Thass in three volumes published by Folklore Resource and Research Centre at St. Xavier’s College in Tirunelveli.

It is to be noted that Thass, along with Reverend John Ratnam, started a movement called the Dravidar Kazhagam in 1882.

Related News: R Ezhilmalai, a Dalit leader who stood apart with friends and foes

“But this fact has been concealed so that no one now remembers Iyothee Thass as the pioneer of the Dravidian movement or anti-Brahmin movement,” writes J Balasubramaniam, assistant professor at the department of journalism and science communication in Madurai Kamaraj University, in an article at Round Table India.

Echoing his view, T Dharmaraj, professor and head of the department of folklore and cultural studies in Madurai Kamaraj University, says Thass had been overshadowed by the Dravidian movement, under Periyar, the Dalit politics, under Dr Ambedkar, and historians contemporary with Thass.

“The then colonial historians never believed that a scholar could emerge from a depressed caste,” he says.

Thass had used oral history, folklore and ancient literature to explain his concepts. But we are reading his works from a modern point of view, which makes us find it difficult to accept his arguments, says Stalin Rajangam, who did a doctoral dissertation on Iyothee Thass. “This doesn’t mean that his arguments were wrong,” he says.

“His interpretations of those folklore and ancient literature disturbed many. Because of that, even his contemporaries like scholar UVe Swaminatha Iyer, poet Bharathiyar, political activist Thiru V Kalyanasundaram hesitated to acknowledge him,” he said.

Dravidian, Tamil and Buddhist

In 1856, a British missionary, named Robert Caldwell, published a book titled, A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South Indian Family of Languages. It was after the publication of this book, the term ‘Dravidian’ gained a place in the linguistic and cultural vocabularies. After Caldwell, the term was largely used by Iyothee Thass. But he used it with a political tone.

In 1881, when the British started to conduct the first Census, Thass urged them to document Pariahs as Adi Dravidars (the original Tamils) and not as Hindus. But the government did not give a heed to his demand. So, he used the term, Dravidian, to denote the Tamils.

Thass also did research in etymology and gave new insights to the words such as pariah, saadhi (caste) and karthigai deepam (a festival of lights in the Tamil month of Karthigai).

An ancient Tamil text, Naradiya Purana Sangai Thelivu written by a Buddhist saint, named Ashvakosh, kindled Thass’s interest in Buddhism.

In 1898, he visited Sri Lanka and got initiation into Buddhism. Later, he began to write a column in his magazine titled Buddharathu Aadhivedham, which described the life and works of Buddha. He claimed that Tamils were Buddhists.

“He explained how the ancient society in Tamil Nadu was. He explained the aspects of Buddhism in the state to a large extent. He used ancient Tamil literature to substantiate his claims. Unfortunately, those texts were not available to modern researchers. So they are sceptical about his views on Tamil Buddhism,” says Aloysius.

They accept Taiwanese Buddhism, Lankan Buddhism, Chinese Buddhism, but not Tamil Buddhism, he says.

Thass believed that Tamils were already Buddhists and asked why should they convert to Buddhism, says Dharmaraj, who wrote a book about Thass. “He explained Buddhism, but lacked agenda,” he says. “What is one supposed to do now? Thass had no answer [to the question] and that’s why his followers never carried forward his works related to Sakya Buddhism.”

When modern politics-based reform movements like the self-respect movement emerged, spiritual-based reform movements like Thass’s Sakya Buddhist movement started fading, says Rajangam. “What is missing in today’s Dalit politics is cultural awareness. Reading and reinventing Thass will help us to reclaim the cultural space that we had forgotten,” he says.