How a Sri Lankan Tamil novel ‘foretold’ Vengaivasal caste atrocity

A dominant community in a Pudukkottai village dropped human faecal matter in a drinking water tank belonging to SCs; this horrific incident is similar to the premise of K Daniel's book, 'Thaneer'

Caste atrocities in Tamil Nadu, the land of Periyar, have once again reared their ugly head. Unidentified miscreants from the dominant community in Vengaivasal village in Pudukkottai district allegedly mixed human faecal matter in the drinking water tank ‘allocated’ for members of Scheduled Caste communities in the area.

The event came to light last week when a few children fell ill after drinking the water. Upon checking the tank, the locals found that a large quantity of human excreta had been thrown into the tank. The residents alleged that since the tank cover had to be removed by more than two people, it was more likely an organised atrocity against Dalits.

The SC community members in the village claimed that they got the drinking water supply after a lot of struggle in 2017 and some sections of the dominant community disliked seeing them enjoy regular water supply.

Also read: Woman in Tamil Nadu booked for refusing to rent house to a Dalit

Though the state has experienced such caste atrocities in the past, people going to the extent of mixing human faecal matter in drinking water was unheard of, at least in the last 20-25 years. There have been reported instances of Dalits being made to eat faecal matter and have faeces poured over them. But mixing human excreta in a water tank so that an entire community gets affected seemed to be crossing all boundaries.

The recent issue got wider attention because of social media and District Collector Kavitha Ramu’s immediate action that included ensuring temple entry for Dalits and filing a case against a saamiyaadi (possessed) woman under the SC/ST Act.

An event foretold

It is a fact that Tamil Nadu and parts of Sri Lanka share many similarities not only on the cultural front but also because caste discrimination is still practised in both these places.

Also read: For poverty-struck, caste-oppressed individual, does religion matter?

The dominant community in the Tamil parts of Lanka are the Saiva Vellalars. The other castes like Nalavars, Pallars, Parayaras, Vannan and Ambattan are grouped as Panchamars, the untouchables. In the 1950s, some groups of Panchamars started to protest against caste atrocities and, in effect, instances like the Vengaivasal episode have happened and continue to happen in Tamil parts of the island nation.

One such incident happened in peninsular Jaffna in the mid-1980s. The dominant community allegedly mixed some toxic substances in the well supposedly located in the land of a dominant community area to prevent the Panchamars from fetching water from it.

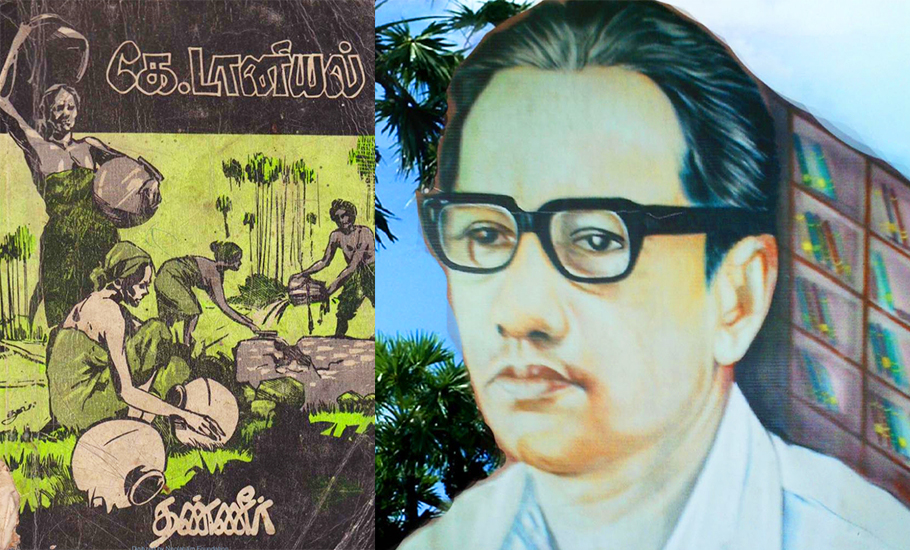

K Daniel, one of the foremost Tamil Dalit writers in Sri Lanka who happened to visit the place, was horrified by the incident and started to pen the novel Thanneer (‘Water’), published in 1987. In the preface of the novel, the author says that he was uncertain when the manuscript would see the light of day as a book.

“However, whenever it gets published, the novel would be suitable for its time,” he said.

True to his words, when one reads the novel in the backdrop of the Vengaivasal incident, it appears to be like ‘an event foretold’.

A hundred-year struggle

Set in Vadamarachchi, Thanneer talks about how the Panchamars’ efforts to construct their own drinking well was disrupted by the dominant community.

The Panchamar community depend on their Vellala landlords for their livelihood. They work on the lands of the Vellalas. There are no public wells, and each landlord has his own well on his land and the Panchamars have to walk more than 6 km every day to collect water. The male landlords are known as Nayinars and their wives as Nayinathis.

The Panchamars are allowed to fetch water from the landlord’s well at a particular time in a day and they can take only two or three pots of water. They are not allowed to dip their pots into the well, but a servant deployed by the landlord would use his bucket to fetch the water and then distribute it to them.

If the dominant caste landlords find any servant defying orders to provide water to the Panchamars, the wells of those members would be polluted with cattle carcass or human excreta.

As the author says, his book Thanneer reveals “the suffering, misery, fury and efforts that Panchamars have faced for over a hundred years to get water in Yazhpanam”.

When caste pollutes water

Chinnan, the protagonist, works in a government hospital as a janitor. He belongs to the Nalavar community, who are considered superior to Parayars. One day, he is reprimanded by a dominant community officer in the hospital for taking food from Maadhan, another janitor and friend of Chinnan, who is a Parayar. Unfazed Chinnan, continues to maintain cordial relations with Maadhan.

This costs him his love affair. Chinnan is an orphan and looked after by Selli, a relative. Even after knowing that Chinnan maintains a friendship with Maadhan, she continues to support him. The dominant community members in the village chide Selli for looking after Chinnan and deny her permission to take water from the landlord’s well. A Nayinathi also cuts off the hair of Selli’s daughter Chinni for being defiant about the water fetching ban.

This in turn leads to a total ban on the Panchamar community to fetch water from other landlord’s wells, too. Due to this, the Panchamars are pushed to steal water from the well of Mootha Thambi Nayinar, another landlord who is out of the village for a medical treatment and oblivious to the developments.

After learning about this incident, Mootha Thambi Nayinar attacks the Panchamar village and sets ablaze their huts. This pushes the villagers to build their own well. Following months of toil, the well becomes a reality. However, before the formal inauguration of the well, a group of dominant community members throw poison into it. Maadhan, who organised the villagers to build the well, alerts them not to take the water by writing on the wall of the well — nanju (poison) — with his own blood. And, that’s how far humans can fall to harm another over the matter of caste.