Caste in Tamil cinema: Karnan raises the bar

A new crop of filmmakers is changing the portrayal of Dalits in Tamil cinema. Vetrimaaran (45), Pa Ranjith (38) and Mari Selvaraj (37) – all belonging to the Scheduled Caste – are taking big artistic risks and changing the way Dalits are represented on screen

A new crop of filmmakers is changing the portrayal of Dalits in Tamil cinema. Vetrimaaran (45), Pa Ranjith (38) and Mari Selvaraj (37) are taking big artistic risks and changing the way Dalits are represented on screen.

The three filmmakers, of course, differ in their approach. While Maran touched upon caste in his 2019 film Asuran, the story was essentially based on a Tamil novel, called Vekkai; in Ranjith’s films the caste component usually centres around heroic characters such as ‘Kabali’ and ‘Kaala’; Selvaraj’s movies offer an unflinching take on caste and the daily ignominies and atrocities suffered by those at the bottom of the heap, as reflected in his debut, Pariyerum Perumal (2018).

Also read: V Anaimuthu – Periyarist and champion of backward classes

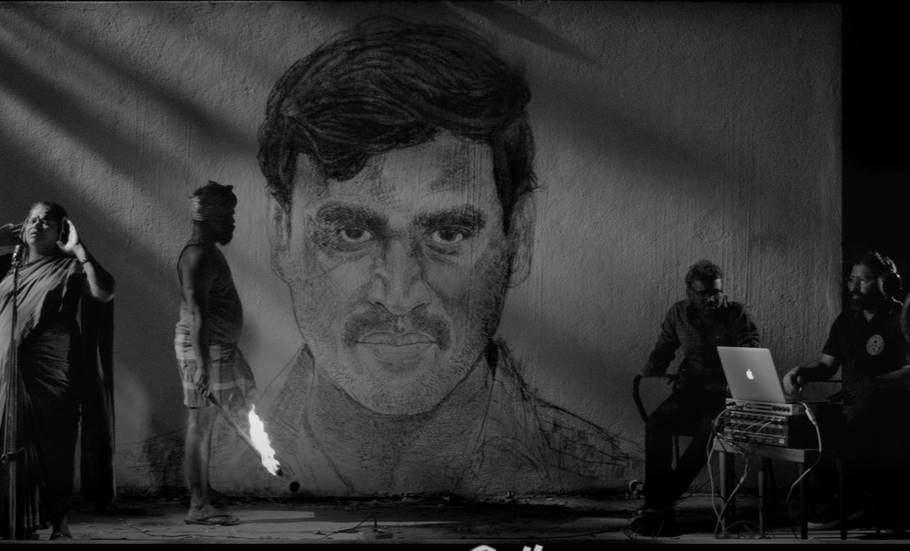

Selvaraj’s latest film, Karnan, which has opened to glowing reviews, is loosely based on the 1995 caste-riots in Kodiyankulam and stars Dhanush in the titular role. The story unfolds at a place called ‘Podiyankulam’. The people who live there are from the Devendrakula Vellalar community. Neither government nor private buses stop at the village. That isn’t because the village does not have a bus stop, but for the simple reason that the villagers are all Dalits. As a result, people find it difficult to make ends meet. The men are unable to go to work, pregnant women are unable to reach hospital on time and youngsters are deprived of school and college studies. A young man rises to fight this discrimination. How the society reacts to his rebellion is what makes the plot interesting.

Causes of Violence

Between 1991 and 1996, during her first term as chief minister, J Jayalalithaa started naming various transport corporations after historical and fictional leaders. For example, she named the transport corporation in Pudukkottai district after Maveeran Alagumuthu Kone, a Yadava icon; she passed a diktat ordering all buses in the district to bear his name. Similarly, buses in Sivagangai and Ramnad districts were named after Maruthu Pandiyars, the historical figures. At the same time, buses in Kanchipuram and Tiruvallur districts were named after MGR.

The trend continued even after 1996, when DMK patriarch M Karunanidhi came to power. Around this time, Devendrakula Vellalars demanded that the transport corporation in Tirunelveli be named after their icon Veeran Sundaralingam. They insisted that buses running in Tirunelveli and Virudhunagar should bear Veeran’s name. Karunanidhi acceded to the demand.

Also read: Give a hoot to owls, they aren’t ominous: TN birders sensitise voters

Thevars, the caste Hindus, were opposed to the naming of a corporation after a caste leader (Veeran Sundaralingam). This caused tensions between the Thevars and the Devendrakula Vellalars.

According to a Human Rights Watch report (1999) on the violence, some Thevars were heard saying: “How do you expect us to travel in a bus named after a Dalit? It is a personal affront to our manhood.”

Why Kodiyankulam Was Targeted

K Ragupathi, who studied the history of Devendrakula Vellalar movement, has another explanation for hostilities between the Dalits and the Thevars

“A Pallar boy and a Thevar girl, both students at government school in Veerasigamani in Sankarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli District, had fallen in love with each other,” Raghupati wrote in his doctoral thesis.

“The headmaster of that school abused the boy for daring to love a Thevar girl. The boy told this to their parents and they met the headmaster, who suspended the student. This came to be criticised and hence the school was closed for some days. When the school was reopened, another problem arose that added to the already prevailing caste tension. A girl student of Pallar caste was being used by a lady teacher to clean the lunch box. But she refused to do it and said: ‘If you ask me to study, I will study. But if you ask me to wash your lunch box, I will not do it.’ The teacher shouted and scolded. ‘You low-caste dog.’ The girl walked out of the classroom and students of Pallar caste also left with her.”

Ragupathi added: “The headmaster diverted this tension in school with the help of his henchman. According to the advice of the henchman, the school students who belonged to the Thevar community disturbed the moving of buses on July 26, 1995. It was opposed by a driver who belonged to the Pallar of Vadanathampatti village and he was severely attacked by the Thevars.”

In retaliation, Pallars attacked some Thevars. Enraged, Thevars picketed buses at a village named Sivagiri. They also ransacked home of Pallars. The violence started to spread to nearby areas. Posters calling Thevars to kill Pallars and abduct their women soon went up. The police were mere spectators; in some cases they participated in the violence against the Pallars.

“Against this background, the Pallars of Kodiyankulam assembled at their village for discussing the ongoing conflict. They passed resolutions such as compensations to families who lost lives, compensation to those wounded by police firing, arresting the biased officers…” wrote Ragupathi.

On August, 31 1995, the police entered Kodiyankulam with 600 personnel. The police damaged food grains by pouring kerosene, poisoned the drinking well with pesticides and fertilisers, and damaged electronic goods. They attacked the elders and harassed the women. The terror of the police started at 10.45am and lasted till 3.15pm.

“It was a village of Pallars and they were economically well off. Every family had a degree holder and the village had produced two IAS officers. Since 1980, the village has become prosperous by migration of many to Gulf countries. The Thevars, who had committed all forms of atrocities against these people in the past, became jealous of the Pallars. Sadly the police behaved like a dominant caste in Kodiyankulam village,” wrote Ragupathi.

Karnan reflects these and other atrocities. In a key scene, the hero tell the villagers that the police did not beat them for damaging a bus, but for raising their voice – against the police and caste Hindus.