A book sought to prove MGR was a Gounder from Kongu land; what was the aim?

To prove he was Tamil, MGR pushed epigraphist Pulavar S Raju to write 'Senthamizh Velir'; its success was limited

The Madras High Court last month declared Edappadi K Palaniswami as the sixth general secretary of the AIADMK, a party founded by matinee idol MGR. The verdict brought to an end the power tussle in the party, which has been raging since June 2022.

After the legal victory, Palaniswami was given a massive reception at the party headquarters in Chennai. Some of his followers crowned Palaniswami with a white cap similar to the fur cap worn by the party founder MG Ramachandran (ostensibly the actor turned politician did it to cover his bald pate). Not just the cap, Palaniswami was also made to wear the black coolers and a shawl.

The photos of Palaniswami aiming for the MGR look went viral on social media. By imitating MGR, many felt Palaniswami sent a message to the rival OPS faction that the party is no longer in the hands of Mukkulathors but the Kongu Vellalars.

Political analyst Tharasu Shyam, however, brushed this move aside as a “gimmick”. “The AIADMK has lost in the parliamentary elections in the Kongu belt even in the times of MGR. During Jayalalithaa’s period, the party was seen as a Mukkulathor dominated one. But, even back in the 2004 parliamentary elections, the AIADMK was wiped out completely. So, this kind of takeover of the party by one caste has never borne fruits,” asserted Shyam.

Projecting MGR as Gounder

In a conversation with The Federal, filmmaker Kavitha Bharathy, who hails from the Kongu region, talks about how MGR tackled the criticisms in the 1980s that he was not a Tamil.

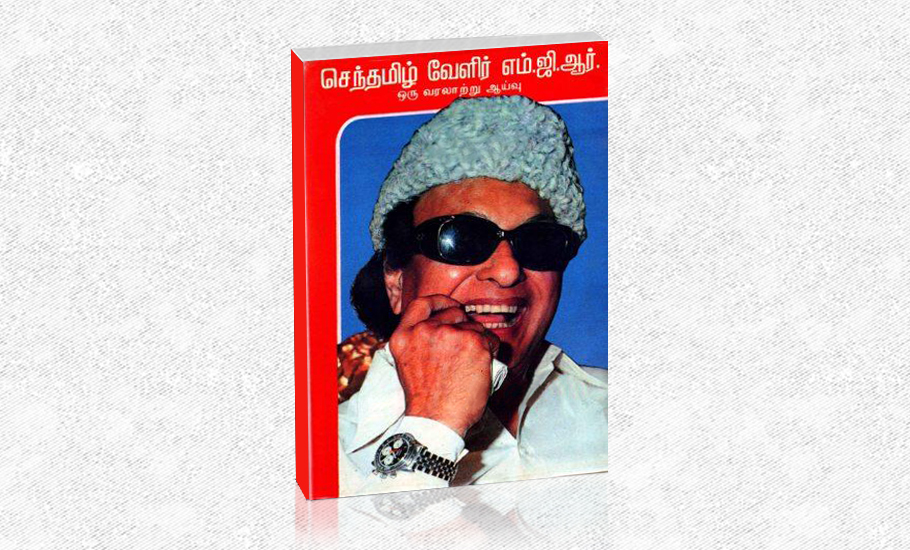

“To counter the allegation, MGR decided to prove that he had roots in Tamil Nadu. He then pushed Kongu-based epigraphist Pulavar S Raju to carry out a study that resulted in a book published in 1985, titled Senthamizh Velir. In this book, the researcher tried to establish MGR as a Gounder,” pointed out Bharathy.

MGR’s fears of being criticised and pushed into a corner for not being Tamil were not unfounded.

Tamil writer Kavya Shanmugasundaram, in one of his articles, claimed that when MGR was emerging as an influential celebrity in the DMK, his on-screen competitor Sivaji Ganesan often criticised him as ‘engirindho vandhavar‘ (a man who came from outside).

Similarly, when MGR founded AIADMK, DMK patriarch M Karunanidhi started to bring up the fact that the actor-turned-politician was a Malayali. Even the poet Kannadasan used to make fun of MGR since he was half Malayali and half Tamil. Popular comedian NS Krishnan, who was senior to MGR in the Madurai Original Boys Company drama troupe, used to call MGR ‘Valladan’, the name of a famous wrestler in Kerala.

Also read: AIADMK@50: The political party MGR built battles for survival

It appears that even before MGR wanted to project himself as Tamil or Kongu Vellalar (also known as Gounder in local parlance), some people from the film fraternity close to him started to claim that the matinee idol was a Kongu Vellalar. One such person was Kovai Chezhiyan, a Dravidian leader, film producer and also one of the key Gounder leaders.

According to political analyst Shyam, “Chezhiyan wrote a column in the daily Anna, and tried to establish the link between the Mannadiyar community in Kerala with the Kongu Vellalars in Tamil Nadu. But, this was nothing but some efforts by his ardent fans and followers to win MGR’s heart.”

AIADMK leader C Ponnaiyan, one of the party’s founding members and a native of the Kongu region, and Congress leader Nalla Senapathy Sarkarai Mandradiyar also played their part in playing up MGR as a Gounder.

Kongu Vellalars and Mannadiyar link

Raju begins his book Senthamizh Velir with the history of the Kongu region.

One of the ancient Tamil texts, Thandiyalangaram, says ‘viyan tamil nadu ainthu’, which means that Tamil Nadu was originally divided into five nadus (countries). In ancient times, besides the three kingdoms Chera Nadu, Chola Nadu and Pandya Nadu, ruled by chieftains, there were two other kingdoms, namely Thondai Nadu (present day Trichy and surrounding areas) and Kongu Nadu (present day Coimbatore and surrounding areas), in Tamil land.

Many historians claimed Kongu Nadu was a separate country and it was never a part of Chera Nadu, which was predominantly ruled from present day Kerala. The people of Kongu land were referred to as ‘Kongars’ in Sangam texts. The olden day Kongu Nadu consisted of present day districts such as Nilgiris, Coimbatore, Erode, Salem, parts of Dharmapuri and Palani.

According to Raju, the Kongu people could have migrated to Kerala due to various reasons including war, famine, marriage bonds, trade and commerce. “They migrated mainly from Kangeyam, Sangarandampalayam, Karur, Pazhaiyakottai, Kaadaiyur, etc., and at first they settled in Chittur, Kollangodu, Palakkad and Alathur,” Raju says in his book.

Also read: PM Modi pays tributes to MGR on birth anniversary

Trying to establish that Vellalars probably migrated to Kerala, Raju said, in Kongu Nadu, many of the Kongu clan leaders were called ‘Mandradiyar’. The term Mandradiyar was a title and names such as Venadudaiya Mandradiyar, Sarkkarai Mandradiyar, Kangeya Mandradiyar, etc., were found in stone and bronze inscriptions. The word has many meanings like judge, protector of cattle, or it can also be a title given by the king.

The author Pulavar S Raju claims that this term ‘Madradiyar’ could have been turned into ‘Mannadiyar’ in Kerala.

It should be noted that C Achutha Menon in his Cochin State Manual refers to the term Mannadiyar as a ‘title of nobility’. LK Anantha Krishna Iyer in his Cochin Tribes and Castes, refers to the term as ‘the title of certain aristocratic families in Chittur near Palghat’.

The Mannadiyars of Kerala still keep in touch with the Kongu region by way of temple rituals. For example, Vadasseri Mannadiyar from Pudussery in Kerala, has the rights to open the west gates of the historic Patteeswarar Temple in Perur, Coimbatore. It is one of the major Saivite temples in the state, says Raju in his book.

Further, he writes, “Both Mannadiyars from Kerala and Mandradiyars in Kongu belt share common cultures such as the same kind of nuptial ‘thaali’ designs, puberty rituals, expecting their women to wear white sarees once they are widowed, and they are worshippers of Goddess Mookambikai and more importantly, both are vegetarians.”

Debate on surname ‘Menon’

In the final part of the 160-page book, the author dedicates a chapter to discuss the use of the surname ‘Menon’. MGR’s father Gopala Menon, was a descendant of the Kongu Vellalar community, and mother Sathyabama was a descendant of Vadavanur Vellalar, who migrated from Kongu and is a close relative of the Mandradiyar community.

MGR’s forefathers could have been served in Vaishnavite temples, says Raju, and hence the names of the descendants have a Vaishnavite impact. MGR’s full name was Marudhur Gopalan ‘Ramachandran’, his first elder brother’s name was ‘Chakrapani’, while his second elder brother’s name was Balakrishnan.

According to Raju, the ‘Menon’ in Gopala Menon is not a caste suffix, but a title given to an accountant or registrar in a village. Raju also quotes the writer of the official report of the 1891 Census, HA Stuart, who states that “the term ‘Menon’ or ‘Menavan’ means a superior person and it is derived from Dravidian Tamil word ‘mel’ meaning ‘above’ and ‘avan’ meaning ‘he’.”

It is interesting to note that even MGR, has never identified himself as ‘Menon’ and it was evident from his autobiography Naan Yen Pirandhen?, in which he claims that no one from his family, relatives or friends ever called him ‘Ramachandran Menon’.

Did Raju’s book have any impact? “Of course, not,” said Shyam. “Even MGR never responded to this book publicly. On the other hand, it was after this claim of him being a Kongu Vellalar, the AIADMK started losing elections in the Kongu region,” he pointed out.

Though the book did not produce the desired effect for MGR, it went on to win the Tamil Nadu government’s award for best book.