UP's ODOP scheme: One District, One Product, 3 sets of export data

There’s discrepancy in data given by various UP government officials; according to one set of figures, ODOP constituted 62% of total exports from UP while according to another, it constituted 72%

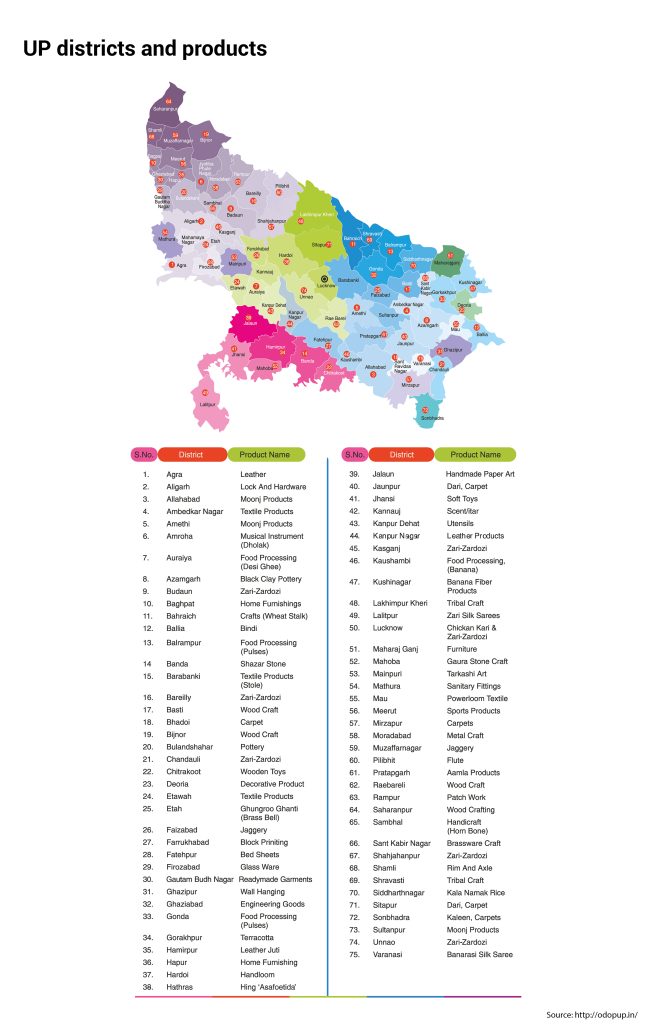

The One-District-One-Product (ODOP) scheme, launched by the Uttar Pradesh government on January 24, 2018, aims at industrial promotion, mainly of craft industries in the informal sector. The 75 districts in UP have been assigned one product each — two in some cases — for focused promotion.

Besides craft products, some agricultural primary products have also been included in this list for promotion through food processing. Subsequently, this scheme was extended nationwide by the Centre.

ODOP, at first sight, appears to be a good idea. But is it big enough to make a significant difference to the overall exports and to the livelihoods of millions of craft workers? Let us examine the ODOP record of UP.

Also read: UP launches cashless medical scheme for govt staff, pensioners

The products listed under UP’s ODOP scheme were also being exported before the introduction of the scheme. As per UP government data, the total value of exports of ODOP products from the state increased from ₹58,000 crore in 2017-18, i.e., just on the eve of introduction of the scheme, to ₹96,000 crore in 2021-22 – that is, by ₹38,000 crore in four years. If this figure is true and if craft products and some processed food products alone had brought about this increase, this is no mean achievement indeed. Assuming this figure to be true, what kind of impact has it made on the ground in the lives and businesses of crafts people?

Lucknow: Chikankari and Zari Zardozi

To get to know this, we started from Lucknow. Chikankari embroidery and Zari Zardozi designer garments are the two ODOP products assigned for the state capital. We first spoke with film-maker Muzaffar Ali, of Umrao Jaan fame, who has also launched an initiative called Dwar Pe Rozi (Employment at Doorstep) to help artisans in marketing exquisite designer items woven aesthetically and in producing design-rich embroidery in Lucknowi Chikankari and Zari Zardozi styles.

Talking to The Federal, Ali said: “The real problem of artisans is that they are forsaking craft work. Paradoxically enough, though they are producing highly skilled, high-value hand-made craft work, it is not able to give them adequate earnings to sustain them and their work. I am not sure the ODOP scheme is addressing the problem of marketing. They are talking of imparting skills through this scheme. But these craftpersons are already highly skilled. I just don’t understand what more skills they can impart.”

Ali felt the Lucknow Chikankari industry remains highly disorganised and, thanks to the middlemen, severely exploited. “The women workers are getting very low wages, but owing to severe poverty they slog at very low wages. Zari Zardozi, involving gold zari work, is dying because it has become very costly and people are buying them very rarely. They are worn only on two-three occasions in a year,” he added. “ODOP scheme doesn’t appear to be making a palpable difference on the ground here. Through our society Dwar Pe Rozi, we are helping the artisans improve the aesthetic dimension of their products and increase their income,” Ali concluded.

As he pointed out, the ODOP scheme has not established any exclusive public sector marketing corporation or export agency to promote marketing of these ODOP products and it has not offered any significant concessions to private emporia marketing them within India or to private exporters selling them abroad. With this key element missing, it is a mystery how exports supposedly increased due to the ODOP scheme.

Varanasi: Benarasi silk

Benarasi silk is the ODOP product for Varanasi. Rais Ahmad Ansari is an exporter of Benarasi sarees, fabric, furnishing material, and garments. Rais told The Federal that he has heard about the ODOP scheme but doesn’t yet know what it offers and whom to approach.

The scheme has not yet reached the people who might be interested. He said that the government, with the help of stakeholders, should organise seminars and get the Weavers’ Service Centre and the Exporters’ Association to invite entrepreneurs and cooperatives who are doing the real work.

“To get a few thousand interested people to come and understand what the scheme is all about would help to kick start the scheme in real earnest,” he observed.

Prayagra: Guava and Moonj products

Next, we talked to some people in Prayagraj (Allahabad). Guava and Moonj (a kind of reed similar to strips of spliced bamboo) products are the two ODOP products listed for Prayagraj. Samina Naqvi is one of the key persons of the organisation Sanchari, which reaches out to producing communities with a unique combination of art and cultural activities and entrepreneurship promotion activities. It is one of the organisers of the Guava Festival in Allahabad.

Samina told The Federal that hers was the only event which was trying to promote value-added guava products. “I got some success initially only because the then district collector was extremely enterprising and helpful. After that it has been extremely difficult as there is no support from the department of MSMEs and export promotion or even the department of tourism or any other government officials. The ODOP scheme is not widely known,” she said.

Fazal Mahmood is an entrepreneur in Bambrauli of Allahabad. Speaking to The Federal, he said he owned a guava orchard with 500 trees. But he was not associated with the ODOP scheme. According to him, “There is a great demand for guava in the Middle-East. For exporting guava products, I need an agent in Dubai round the year, but can I afford it? There should be regular seminars, workshops and events to popularize the ODOP. Additionally, the traditional charpai, the hammock, bags and baskets can be prepared from moonj and sold abroad. But now other materials and plastic are being used and nobody is bothered. The ODOP should first reach the doorstep of the small producer, or farmer, and only then we can evaluate its benefits.”

Piyush is the founder of Happy Cultures, a community enterprise which has adopted some villages in an area with 60 km radius in and around Allahabad for promoting Moonj products. Talking to The Federal, Piyush rubbished the tall claims of the UP government about the success of the ODOP scheme. This scheme has done more harm than good to the artisans of moonj, he observed.

Piyush, who comes from a corporate background, said he is fed up with the red tapism and corruption in the implementation of the scheme, more than 99 per cent of which is done through NGOs. Though each farmer-entrepreneur is entitled for ₹30,000 under the scheme, the NGOs keep ₹15,000 for themselves and give only the remaining ₹15,000 to a section of farmers. Only handmade stuff has export value. So, whatever machine products are made, get dumped, defeating the very purpose of the scheme.

Sudanshu Agarwal of RN Handicrafts of Moradabad, manufacturing metal crafts, and Jamshed from Hindi International, Jajmau, Kanpur, producing leather products, told The Federal that nobody had heard of ODOP in their area.

Ramnaresh from Pratapgarh said amla murabba and laddu are manufactured in one small old unit near Chibila and no new units have come up. Still, amla has been notified as the ODOP product of the district. Amla products are sold in Prataphgarh and a little in Allahabad and nowhere else, he added.

Discrepancy in official data

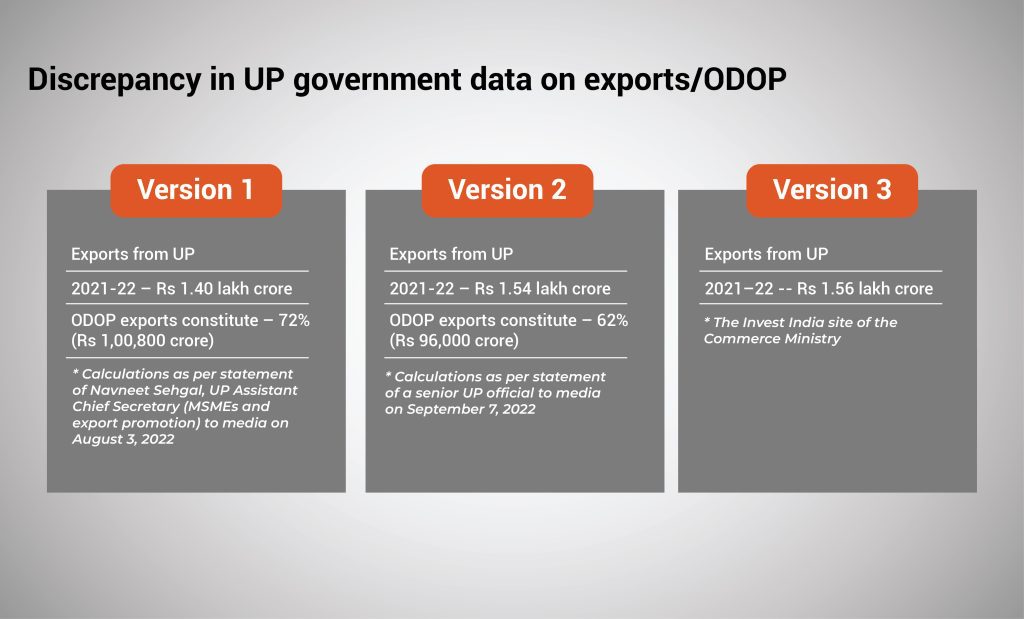

There seems to be some discrepancy in the exports data put out by UP government officials. On September 7, 2022, in a media briefing, a senior UP official claimed that the export of ODOP products from UP increased from ₹58,000 crore in 2017-18 to ₹96,000 crore in 2021-22. The official also reportedly claimed that these ₹96,000-crore ODOP exports constituted 62 per cent of the total exports from Uttar Pradesh.

If this is so, then the total exports from the state in 2021-22 would have been ₹154,839 crore. But, the chief architect of the ODOP scheme, Navneet Sehgal, Uttar Pradesh Assistant Chief Secretary (in-charge of MSMEs and export promotion), informed the media on August 3, 2022, that exports from UP increased from ₹1.07 lakh crore in 2020–21 to ₹1.40 lakh crore in 2021-22 of which ODOP exports constituted 72 per cent. The Invest India site of the Commerce Ministry puts the figure of exports from UP in 2021–22 at $21.1 billion or ₹1.56 lakh crore. One wonders which one of these figures is correct.

If this 72 per cent figure is true for ODOP exports in 2021-22, then they work out to ₹1,00,800 crore and the non-ODOP exports should have been ₹39,200 crore. But then, as per APEDA (Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority) data, UP exported ₹15,752 crore worth of buffalo meat in 2021-22.

Besides this, as per the data from the UP Export Promotion Council site, UP exported non-ODOP items like ₹25,615.81 crore worth of electrical machinery, ₹10,137.31 crore worth of textiles, ₹3,339.36 crore worth of sugar, ₹3,766.22 crore worth of organic chemicals, ₹1,890.35 crore of plastic products, and ₹5,956.65 crore worth of iron and steel products in 2021–22, to cite only a few. Thus, composite figures of ODOP and non-ODOP product exports do not tally with overall export figures.

Also read: Agnipath scheme will give new dimension to youth: Yogi Adityanath

The UP state budget in 2018-19 allocated only ₹150 crore for the ODOP scheme. It is really astonishing that with an initial expenditure of ₹150 crore, the state managed to increase its exports by ₹38,000 crore in four years — this increase is being attributed to the ODOP scheme alone though the scheme has no institutional mechanism to increase exports or domestic marketing.

Hard facts on ODOP exports are not available on any of the UP government sites, including the official ODOP site. Are the state officials making exaggerated claims to please the powers that be?