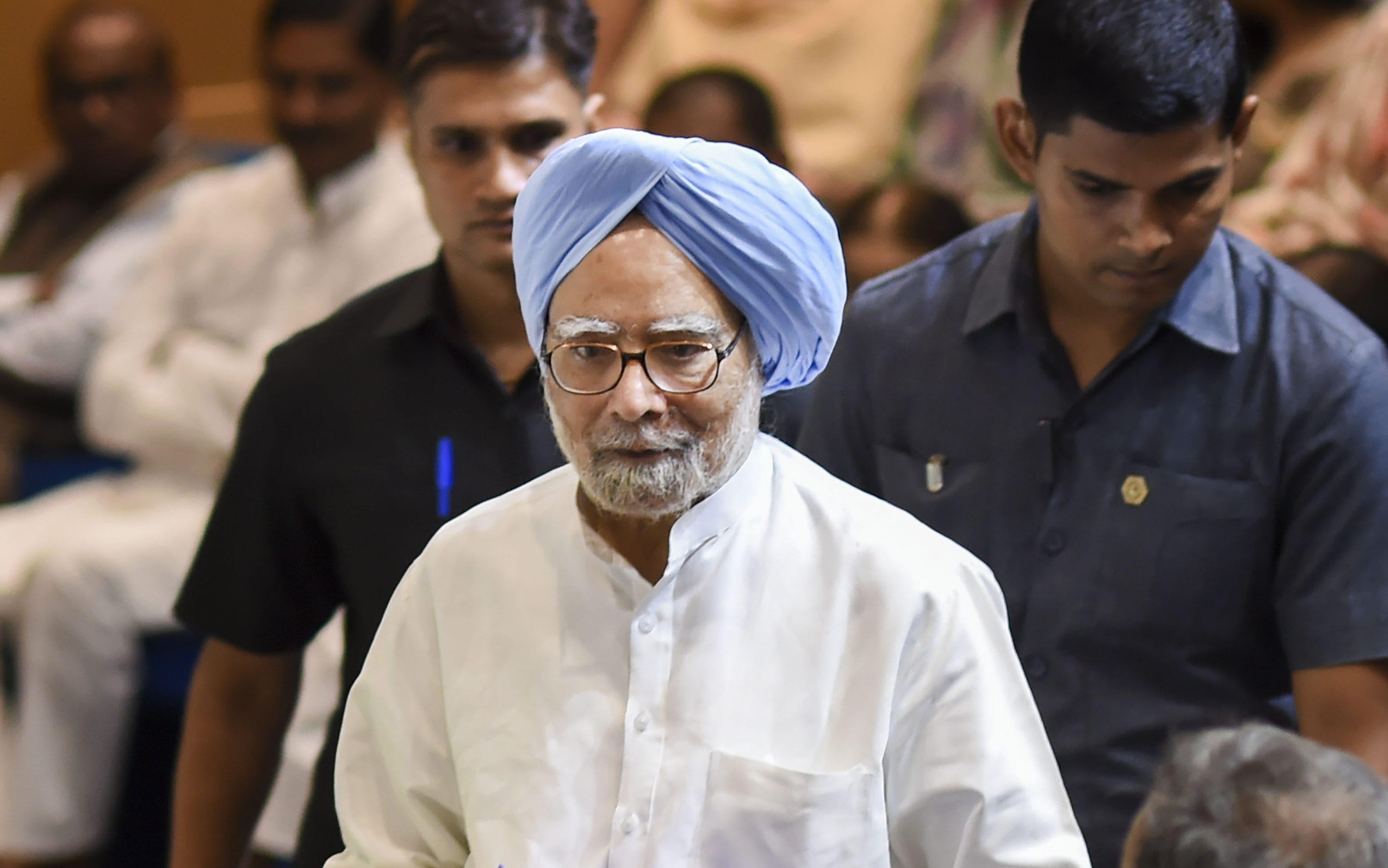

Chaos, clash and slowdown: Why it's time to revisit Manmohan’s legacy

History, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh once poignantly said, would be kinder to him than the media. He might have been rephrasing the old argument that some people are born ahead of their time and, thus, not fully understood by their contemporaries.

History, former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh once poignantly said, would be kinder to him than the media. He might have been rephrasing the old argument that some people are born ahead of their time and, thus, not fully understood by their contemporaries. And that some people become metaphors for their time and are, thus, valued much more than what they are worth.

French philosopher and writer Albert Camus had a brilliant argument on this. “There always comes a time in history when the person who dares to say that 2+2=4 is punished by death. And the issue is not what rewards or punishment be the outcome of this reasoning. The issue is simply whether or not 2+2=4.”

Six years is just a dot on the continuum of time. But, it seems that we are on the cusp of a period of enquiry where we’d soon start revision of the Manmohan Singh (MMS) era, its history and our evaluation of it. May be, we’d start telling ourselves, the gentleman PM, whose silence we lampooned as weakness, may have been wrongly excoriated for saying 2+2=4.

With the passage of time, two stark differences between the MMS era and the time we live in have started to emerge.

One in the handling of the Indian economy, which, at the moment, is in free fall. Another in the way India went about its life till the previous decade — the calm, unhurried manner in which the government went about its task having been replaced with a sense of chaos, uncertainty and apprehension. As a consequence, India now appears edgy, excited and in perennial confrontation.

ALSO READ | Govt should reach out to thinking minds to save economy: Manmohan

The accidental economy

It is clear now that the Indian economy is reeling under the impact of two ‘big-ticket’ initiatives by the Narendra Modi government. The government’s decision to outlaw currency notes of ₹500 and ₹1,000 denomination in October 2016 started the destruction of our economy. It was hastened by the faulty implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST).

Soon after the government withdrew the currency notes, former PM Singh had argued in Parliament that the decision will lead to at least two per cent decline in growth. And three years later, the fall has been much more pronounced and sustained.

Unemployment (9 per cent) is rising, investor confidence has fallen and demand has disappeared. Amidst the overarching gloom and doom, nobody is sure if the economy can be revived, and if so, how fast from its current low of 4.9 per cent.

Reams have been written on the impact of demonetisation on the GDP. So, a synopsis would suffice: it killed small and medium businesses dependent on cash, wiped out jobs, savings and unnecessarily locked up money in bank accounts. India’s informal economy that depended on cash transactions suffered a huge setback and has still not been able to recover.

ALSO READ | Lowest growth numbers in 6 years point to serious crisis

To this mess, the government contributed more tumult with a half-baked GST. This tax made business complicated for small and medium traders, raised costs, hit demand and contributed to the build-up of large inventories.

As a result, the government’s own tax collections have suffered, sliding below the one lakh crore mark in August. This figure is crucial because the government needs over ₹1 lakh crore GST to achieve its fiscal target. Low collections also make it incumbent on the Centre to compensate states for the losses they incur in the first five years of the implementation of GST.

A bit of this slowdown is because of global factors, especially the trade wars triggered by Donald Trump’s myopic US-first policy that is threatening to destroy his own country.

It is also true that nobody can say with certainty if Singh would have fared better. But, it can be said with certainty that he would not have disrupted the economy with ill-advised measures like demonetisation and the slapdash implementation of GST. After all, Singh had steered the economy much better during his 10 years in power through periods of low growth in spite of high prices of crude.

ALSO READ | If you can’t give them bread, give them beads and boost GDP again

Chaos and confrontation

In this context, it is instructive to revisit Singh’s recent comments on the state of our economy. A day after the GDP growth fell to a six-year low of 4.9 per cent, he urged the Modi administration to set aside its “vendetta politics” and reach out to all “sane voices and thinking minds” to find ways of steering the economy out of “this man-made crisis”.

Vendetta may indeed be one of the defining themes of the times we live in. But, it is directed not just at individuals and rivals — a hallmark of low grade competitive politics — but also against communities and groups of citizens.

Over the past five years, confrontation with groups and societies that do not suit the BJP’s ideology has peaked. In the Modi government’s first, liberals, free-thinkers and those who believed in India’s secular ethos were targeted.

Simultaneously, self-anointed vigilantes and flag-waving thugs created an atmosphere of fear in the name of cow, beef and pseudo-nationalism. These conflicts continue but seem less ominous compared to the chaos unleashed by recent events in Jammu and Kashmir, and Assam, where millions of people are facing the consequences of the government’s actions.

ALSO READ | When will Kashmiris see a normal, peaceful day again?

In 2016, in the run up to the Assembly polls, the BJP took advantage of the fault lines in Assam by bringing the issue of “illegal immigrants” on top of its election agenda. It raised the communal pitch by comparing the election with the “last battle of Saraighat” — a 17th century clash against Mughals led by the indigenous Ahoms. The subtext of the campaign was clear: if people wanted to defeat the new-age invaders — the Muslims from the eastern borders — they had to vote for the BJP.

Four years later, after promising to throw the ghuspaithiyas out of the state, giving exaggerated numbers of illegal immigrants, the BJP is struggling to handle the national registry of citizens (NRC) for Assam.

Amidst unprecedented chaos, its own leaders are calling the entire exercise futile because it didn’t vindicate the BJP’s propaganda that every third person in Assam is an illegal immigrant. It is evident that the BJP pushed Assam to the brink just to indulge its communal agenda, fantasies of Hindu supremacy and fibs.

Another pre-poll promise, that of abrogating Kashmir’s special status, has resulted in an unprecedented lockdown in the Valley. Under the blanket of curfews, internet and phone shutdowns, and heavy restrictions, the Valley is simmering with rage. Nobody knows how it would react once the restrictions are eased.

ALSO READ | ‘Illegal’ migrants yes, but unfair to assume they are evil

Meanwhile, across the world, Kashmir is resonating as an example of India’s tyranny; newspapers and television channels in the West are bombarding readers with images and reports of brutality and oppression.

The point is this: from the country’s northern borders, to the banks of the Brahmaputra on the eastern end, there is an uneasy smog of uncertainty and confrontation. The government is at loggerheads with large sections of its own society. This sense of being in perpetual conflict is likely to prevail with the Hindutva brigade itching to enforce the remainder of its wishlist — the Ram temple in Ayodhya, Uniform Civil Code, et al — on the country.

This feeling of unease, the growing fear that some sections of the society — primarily its minorities — are under siege is a precipitous change from the relative calm and culture of consensus during Singh’s tenure.

The exact moment the country starts noticing the change in the country’s mood, the stark contrasts between the two governments, would be the right time to evaluate Singh’s legacy. And that moment isn’t too far away.

ALSO READ | Being Modi: The political dynamics of abrogating Article 370