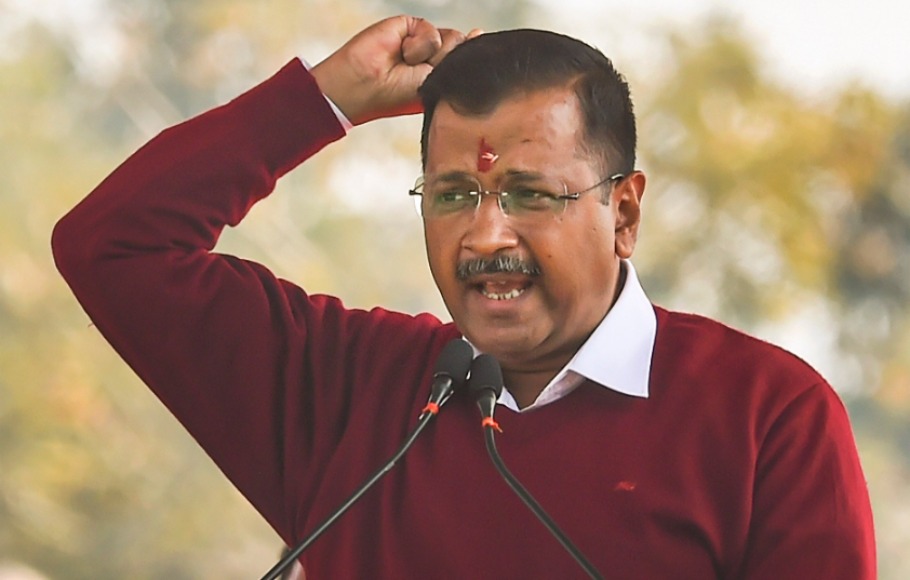

Reunification of Delhi municipal bodies: Why is Kejriwal taking on BJP?

The Centre’s arbitrary and unilateral decision to merge three municipal corporations of Delhi has finally ended the long ceasefire of verbal hostilities between Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal and the BJP.

The Delhi Municipal Corporation (Amendment) Bill, 2022, introduced in the Lok Sabha, on March 25, seeks to merge the municipal corporations of north, south and east Delhi into one corporation. Once enacted, the Bill will reverse the 2011 decision of the erstwhile Congress-led government under Sheila Dikshit that had, through an amendment to the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957, trifurcated the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD).

The Centre’s justification for merging the three corporations is that such a move will improve the administrative efficiency and financial health of these bodies. Since the trifurcation in 2011, the functioning of these corporations has been increasingly constrained by poor administration, repeated strikes by employees protesting non-payment of salaries and arrears, drying revenues and long delays by the AAP-led Delhi government in clearing dues owed to these bodies.

Delhi Chief Minister Kejriwal’s criticism of the Bill, interestingly, is not about its content; he hasn’t explained whether his AAP wants a unified MCD or is for a multiplicity of civic bodies. Kejriwal’s diatribe essentially has been two-pronged. First, he claims that the Centre’s move is a tactic to delay counsellor elections for the three bodies for fear of losing these to the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). Secondly, he insists that an AAP imminent victory in the municipal polls will end the BJP’s corruption in these civic bodies.

The BJP has enjoyed unimpeded control of the municipal bodies for nearly 17 years despite its failure to wrest power – first from the Congress and later the AAP – in the Delhi Assembly polls. The Delhi State Election Commission was informed about the Centre’s decision to reunify these three bodies just hours before it was reportedly going to announce the poll schedule. These elections were due next month. The AAP, riding high on its historic victory in the Punjab assembly polls earlier this month and the continuing popularity of the Kejriwal government in Delhi, had been hopeful of finally ending the BJP’s stranglehold on the three corporations.

There are numerous legal, administrative, logistical and even ethical grounds on which the proposed merger can be debated over. Similarly, there are arguments and counter-arguments aplenty on the timing of the Bill, the BJP-led Centre’s motivations behind it and the evident transgressions against the basic structure of the Constitution by depriving the Delhi MLAs any say in a matter that should have, like the 2011 Bill, be moved in the Delhi Assembly and not the Parliament.

However, Kejriwal has chosen to singularly link the Centre’s Bill to elections and declared in his characteristic bluster, that his AAP will “quit politics” if elections to the unified MCD are held as per the schedule and the results are in the BJP’s favour. Herein, perhaps, is a tale that requires further exposition, particularly in light of the recent uptick in the AAP’s electoral fortunes and its renewed expansionist agenda.

Also Read: Will AAP’s Punjab win strengthen India’s alternative political front?

It’s been a while since Kejriwal marshalled his acerbic tenor to wage war against the BJP, or more specifically, against Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Exactly a year ago when the Centre drastically curtailed powers of the Delhi government and the Delhi Assembly through the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi (Amendment) Act, 2021, Kejriwal made only perfunctory protests.

The GNCTD Act 2021 impinged upon the powers enjoyed until then by the Delhi CM, his government as well as the Delhi Assembly where the AAP has, for two consecutive terms, enjoyed a brute majority. In an evidently flagrant violation of a 2018 verdict by a constitution bench of the Supreme Court that the AAP government’s lawyers had fought hard to get for nearly three years, the GNCTD Act emasculated Delhi’s Executive and turned the Delhi CM, his administration and the state Assembly into nothing more than a rubber stamp for endorsing the Centre’s commands issued through the Lieutenant Governor.

The implications of the amended GNCTD Act were far more adverse for Kejriwal and the AAP than the Centre’s present plan, which has, in fact, attracted much appreciation from those directly affiliated with the three municipal bodies. Yet, besides staging a daylong protest at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar against the amended GNCTD Act, Kejriwal and AAP did little else. Even a legal challenge to the Act in the Supreme Court was not made by the AAP. The Delhi CM’s muted response was at significant variance his strident campaign for full statehood of Delhi – a plank on which the AAP had previously sought votes.

Kejriwal’s silence against Modi and the BJP had also been deafening when, within days of the AAP’s spectacular return to power in Delhi in February 2020, riots broke out against Muslims in the national capital’s northeast district. The riots were preceded by incendiary speeches by BJP’s Union minister Anurag Thakur and Delhi leaders who openly went around hurling slogans such as ‘Desh ke gaddaron ko, goli maaro…’. The riots and the rabble-rousing that preceded them evoked a sharp response and even a rare press conference by Congress president Sonia Gandhi demanding the resignation of Union home minister Amit Shah, Kejriwal. AAP, however, offered no such offensive.

Kejriwal’s sudden machismo against the BJP over an issue such as the merger of municipal bodies, thus, begs the question – what’s changed for the AAP convenor? Fortunately, the answers aren’t difficult to decipher.

It has escaped none that the return of an obstreperous Kejriwal coincides with his party’s first success in wresting control of an Assembly beyond Delhi. The historic win in Punjab also presents a peculiar situation where a party’s boss has significantly lower administrative powers as chief minister than his counterpart in Punjab. The newly sworn-in Punjab CM, invariably addressed by Kejriwal as “mera chota bhai Bhagwant”, has the advantage of ruling over a full-fledged state and, as such, being vested with powers that are more extensive than the AAP convenor who, at best, is CM of a quasi-state with powers that are largely at the mercy of an LG, who is often antagonistic to his administrative vision.

The AAP, as Kejriwal claims, was confident of sweeping the municipal polls in Delhi. If such a victory were to indeed come to pass, Kejriwal and AAP would have witnessed a sudden surge in their powers and, by extension, their capacity to deliver on populist promises. Given the complex administrative structure of the national capital territory where the state government, ironically, enjoys fewer powers on a range of issues than municipal corporations, being simultaneously in control of three major civic bodies as well as the assembly would have significantly enhanced the AAP’s ability to implement its governance agenda and, perhaps, even broken the AAP’s jinx of not being able to win any Lok Sabha seats in Delhi when the general elections are next held in 2024.

The other plausible reason for Kejriwal breaking his self-imposed restraint against the BJP is that following the AAP’s success in Punjab, the Delhi CM wants to expand his party’s electoral footprint in other states. First up are Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh, states due for polls at the end of this year, where the BJP is in power. Both these states have traditionally had bipolar contests between the BJP and the Congress.

Also Read: After Punjab, AAP aims to make a splash in Mumbai’s BMC election

The AAP has made it clear that it wants to break this binary and emerge as the BJP’s principal challenger in both states, obviously after elbowing out the Congress as it has successfully done in Delhi. Additionally, Gujarat is Modi’s home state and the Prime Minister is still the party’s biggest vote catcher there – and elsewhere, for that matter. Among other states that will go to polls in 2023 and where again, the AAP wishes to expand despite being non-existent at the moment are Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh – also bipolar with the BJP and the Congress being the only contenders for power.

It is impossible for Kejriwal to refrain from attacking the BJP any longer if it hopes to dent or displace the party in any of these states. Of course, an obvious undercurrent in this scheme is to squeeze the Congress out of contention – something the BJP may be only too happy about. As such, while the AAP may not find its run for power in Gujarat, Himachal or elsewhere to be as smooth as Punjab, where the BJP was anyway not a key contender and poll prospects for the AAP had aligned due to several other factors, Kejriwal can at least hope to usurp much of the ground presently held by the Congress.

With the Congress struggling to set its house in order, Kejriwal and his AAP believe they can present themselves as a realistic alternative to the Grand Old Party within the broader canvas of BJP’s Opposition. Similar efforts by Bengal Chief Minister and Trinamool Congress chief Mamata Banerjee have, so far, failed to yield any results while the Punjab victory has given some credibility to AAP’s assertions of being able to fill the void being created by a crisis-ridden Congress.

It would, thus, be naive to believe that the brouhaha kicked up by Kejriwal over the reunification of the Delhi municipal bodies and the elections to them is borne out of any concern for legislative praxis or constitutional morality. It’s vintage Kejriwal and his pure political expediency at work.