How UP govt's delay to fix tender has put expecting mothers at risk of diabetes

In view of the high chances of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) in expecting mothers and newborns, the central government under the National Health Mission (NHM) made universal screening of pregnant women for GDM mandatory in 2014. Even though the Uttar Pradesh government, given its high maternal and infant mortality rates, has strictly implemented it in 36 of 75 districts, its failure to finalise a tender for subsidised glucose pouches for the oral glucose tolerance test, has stalled the GDM screenings in the state for the past many months, putting thousands of mothers and unborn babies at risk.

Curse of a lifetime

According to doctors, GDM or diabetes during pregnancy is one of the diseases that affects both the mother and the child not only during pregnancy but even after. It results in a higher risk of babies dying in the womb in or after the 28th week of pregnancy (stillbirth), of neonatal deaths (within 28 days of birth), low birth weight babies (less than 2.5 kg) and large babies (the ideal birth weight is 2.5 kg to 3.5 kg).

“You are what your mother ate,” says V Seshiah, a former professor of Madras Medical College, adding that “diseases that have a foetal origin are almost impossible to cure.”

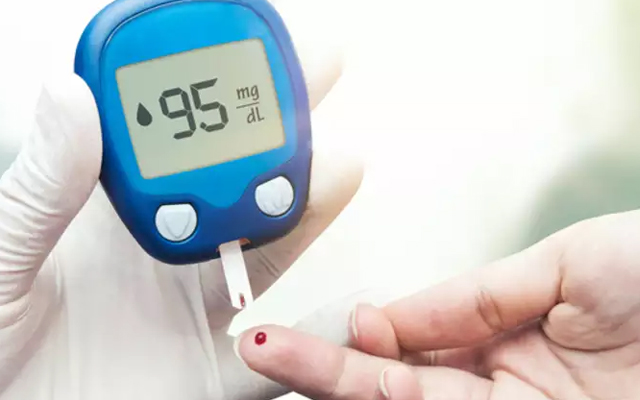

Studies have shown than Indian women have an 11-fold increased risk of developing glucose intolerance during pregnancy than Caucasian women. Gestational glucose intolerance (GGI or pre-diabetes in pregnancy) is blood sugar level in the range of 119-139 millilitres per decilitre of blood (mg/dl), while GDM is blood sugar level above 139 mg/dl.

The threshold levels for both are lower than in men and non-pregnant women, who are considered to be glucose intolerant if their blood sugar level is between 140 mg/dl and 199 mg/dl and diabetic if it is higher than 199 mg/dl. So a glucose intolerant, non-pregnant woman would be gestational diabetic if pregnant. The threshold is lower for pregnant women, because the foetal renal blood sugar level should be 110 mg/dl or less. Ideally, pregnant women must have fasting blood sugar levels of 80-90 mg/dl and post-meal blood sugar levels of 110-120 mg/dl.

Testing for GDM, the sooner the better

Seshiah says he advises his patients to test their blood sugar levels as soon as they know they have conceived. The government-introduced norms for universal screening of GDM require pregnant women to be tested for blood sugar at their first contact with an ante-natal clinic in the public health system – it could be a sub-centre, a primary healthcare centre, a community healthcare centre or a district hospital. During the test, expecting mothers are given 75 grams of glucose dissolved in 250 ml of water, and the test is done two hours later. If they test negative, a second one is done between the 20th and 24th weeks of pregnancy, so that corrective action can be taken by putting them on medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and at least 30 minutes of daily physical exercise. The term of a pregnancy is 39 to 40 weeks.

MNT is a diet that allows the woman to add 300-400 grams of weight per week subject to a maximum of 10-12 kg during the pregnancy without raising her blood sugar levels abnormally. If exercise and diet do not work, she is to be put on Metformin, a drug, or insulin.

This is because above normal blood sugar levels pose an increased risk of caesarean section (apart from those mentioned earlier). Women with GDM have a seven-fold higher risk of developing Type- 2 diabetes. This risk increases steeply five years after delivery. They also have a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. Children of GDM mothers have a higher risk of obesity and diabetes. About one third of children born of diabetic pregnancies develop glucose intolerance before the age of 17.

Relation of diabetes and pregnancy

There is no national level data on the prevalence of GGI and GDM. But a study conducted in Kanpur Nagar district between 2012 and 2014 put the prevalence rate at 13.4 per cent. Another study conducted for a year in 2016 at Queen Mary Hospital attached to King George’s Medical University put the prevalence rate at 13.9 per cent.

The government’s GDM guidelines (for NHM) say worldwide one in 10 pregnancies is associated with diabetes. In India, the rate varies between one in seven and one in 10. It is likely to be one in five, the introduction to the guidelines said. As of 2010, there were an estimated 22 million women with diabetes, between the ages of 20 and 30 years. An additional 54 million women in this age group had impaired glucose tolerance or pre-diabetes with the potential to develop GDM if they became pregnant. If diabetes was a lifestyle disorder associated with prosperity, the number would be higher now.

In 2018, a team of doctors led by Rajesh Jain, the manager of the diabetes control project in Uttar Pradesh, published the results of a study based on the screening of a little over half-a-million pregnant women in the state. Of the women who had GDM, a subset – 12,784 – was followed up. Jain and his team found that 406 or 3.17 per cent of the pregnancies had resulted in stillbirths. Another 7,287 women who did not have GDM were also observed. The number of stillbirths among them was 92 or 1.26 per cent. Neonatal deaths were 191 (1.49 per cent) and 47 (0.6 per cent) respectively. The total number of perinatal deaths – deaths of babies between the 28th week of pregnancy and within 28 days of birth – among women with GDM was 597 (4.67 per cent), much higher than among those who did not have GDM: 139 (1.91 per cent).

How a small glitch can be perilous

After the government made universal screening of pregnant women for GDM mandatory in 2014, states have been gradually rolling it out. Tamil Nadu had taken the lead much ahead of the government’s mandate – since 2009, becoming a model for other states. Uttar Pradesh, according to Jain, accounts for the most number of screenings. It is a large state with high maternal and infant mortality rates, which can be partly ascribed to higher-than-normal blood sugar levels in pregnant women. The state has also made screening for GDM mandatory in 36 of 75 districts. Healthcare professionals – doctors, nurses and auxiliary nurse midwives – in the other districts are being trained in doing blood tests and controlling blood sugar levels.

But, although the universal screening for GDM hasn’t covered all of the country’s district even after five years of its launch, the programme has been stalled in Uttar Pradesh, just because the state has been unable to finalise a tender for purchase of 75-gram glucose pouches. These pouches were earlier supplied by a private company for ₹9.90 each.

An email sent early last week to Usha Gangwar, general manager, Maternal Health, NHM (UP) did not elicit a response despite reminders by email and text messages.

The oral glucose tolerance test costs about ₹20, says Seshiah. “By failing to do even this basic test mothers who have GDM are exposed to a lifetime cost of ₹20 lakh or more, he says. It is time that chief ministers and civil servants who helm the health ministries assumed responsibility and put an end to wanton disabilities and deaths caused diabetes in pregnancy,” he adds.