3D-printed tissues may help treat athletes' injuries

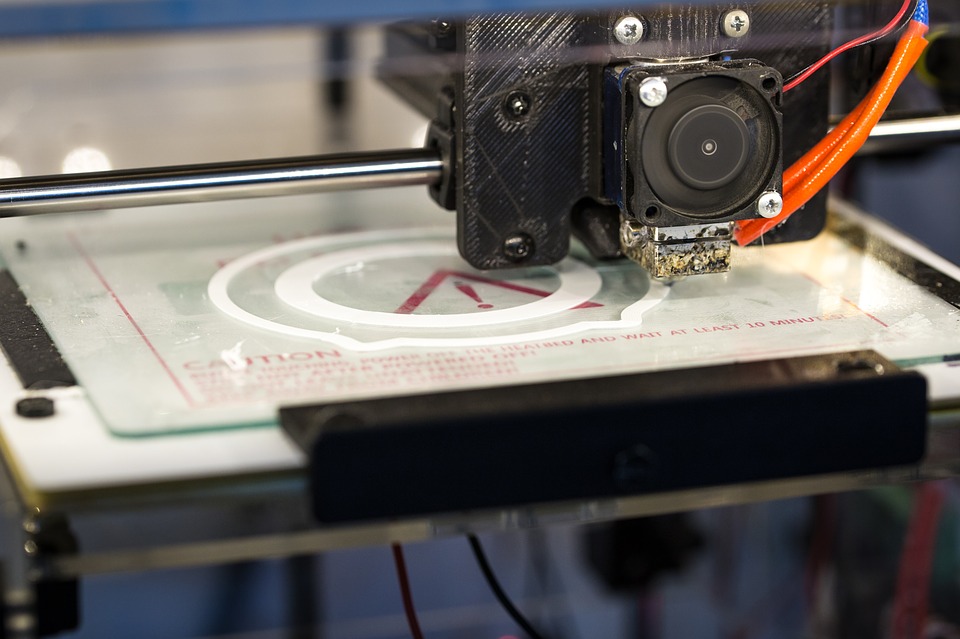

Scientists have developed 3D-printed artificial tissues that may help heal bone and cartilage typically damaged in sports-related injuries to knees, ankles and elbows. The scaffolds replicate the physical characteristics of osteochondral tissue hard bone beneath a compressible layer of cartilage that appears as the smooth surface on the ends of long bones. Injuries to these bones, from small cracks to pieces that break off, can be painful and often stop athletes’ careers in their tracks.

Osteochondral injuries can also lead to disabling arthritis. The gradient nature of cartilage-into-bone and its porosity have made it difficult to reproduce in the lab, according to the study published in the journal Acta Biomaterialia. Scientists at Rice University and the University of Maryland in the US have used 3D printing to fabricate what they believe will eventually be a suitable material for implantation. “Athletes are disproportionately affected by these injuries, but they can affect everybody,” said Sean Bittner, graduate student at Rice University. “I think this will be a powerful tool to help people with common sports injuries,” Bittner said in a statement.

The key is mimicking tissue that turns gradually from cartilage (chondral tissue) at the surface to bone (osteo) underneath. Researchers printed a scaffold with custom mixtures of a polymer for the former and a ceramic for the latter with imbedded pores that would allow the patient’s own cells and blood vessels to infiltrate the implant, eventually allowing it to become part of the natural bone and cartilage. “For the most part, the composition will be the same from patient to patient. There’s porosity included so vasculature can grow in from the native bone. We don’t have to fabricate the blood vessels ourselves,” Bittner said.

The future of the project will involve figuring out how to print an osteochondral implant that perfectly fits the patient and allows the porous implant to grow into and knit with the bone and cartilage.