The coming out of Superman: How we got here and what it means

It’s been barely two months since DC Comics took the internet by storm when it revealed that Batman’s sidekick Tim Drake, a.k.a Robin, was actually bisexual. On Monday (October 11), the U.S-based comic industry giant has taken another bold step by announcing that Superman too will be coming out as bisexual in an upcoming November issue of the comics.

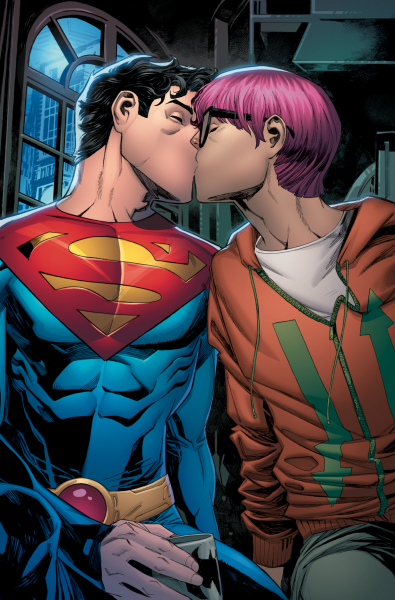

DC chose National Coming Out Day, which falls on October 11, to declare that Jon Kent—son of Kryptonian Clark Kent and Daily Plant reporter Lois Lane—will be seen in a same-sex relationship with his male friend Jay Nakamura in “Superman: Son of Kal-El #5.” A description of the issue reads: “Just like his father before him, Jon Kent has fallen for a reporter,” and adds that the two will be “romantically involved.”

So—why is this a big deal? Well, for starters, it’s not Spider-Man or Batman or Iron Man. Nor is it Marvel’s “Northstar.” We’re talking about Superman here: a traditionally heterosexual superhero since the 1930’s, who is, arguably, the strongest superhero across universes. But for those following Jon’s journey ever since he was put into circulation in July earlier this year, it’s been pretty clear from the start that he’s not much like his father. Sure, he has superpowers, and sure, he’s also been Super Boy in the past, but besides that, he has also been seen stopping a high school shooting, protesting against the deportation of refugees in Metropolis, and fighting against wildfires caused due climate change. Jon is how we would want our superheroes to be today: relatable, raw, and realistic.

Also read: Tovino Thomas’ superhero movie Minnal Murali to premiere on Netflix

The coming out of Superman is proof that genetic coding in mainstream comic books has come a long way. Both, DC and Marvel, stayed clear of LGBTQ characters or any such references in its mainstream comic books for decades during the initial years of the comic industry—but this was primarily due to “The Code.” The fact is that from 1954 to 1989, U.S comic books had rules against portraying LGBTQ characters—enforced by a private organization known as the Comics Code Authority. Technically, this wasn’t government censorship, but still, newsstands and bookstores weren’t going to risk carrying a comic book that didn’t have The Code’s approval.

Ten years after Superman’s debut in 1938, a psychiatrist by name of Dr. Frederic Wertham began speaking out quite vociferously against mainstream mass media—comic books in particular—and claimed that these could corrupt American children. In 1954, he published a book called “Seduction Of The Innocent” in which he raised concerns about the gore, violence, and sex portrayed in comic books, and in one section, even described the Caped Crusader and Boy Wonder as “a wish dream of two homosexuals living together.” Soon after his book was published, Wertham appeared at a congressional hearing before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency and testified that comic books were a major cause of juvenile crimes. Although there was no ruling that advocated for government intervention or censorship in comic books, the subcommittee made it clear that the comic book industry needs to take into account how its publications could adversely affect American values and asked that it (comic book industry) set standards on what they could and could not depict—eventually leading to the formation of The Comics Code Authority in 1954.

The Code framed various rules such as how violence was to be portrayed, how characters should appear, as well as how government figures could be portrayed. According to an article written by comic book historian Alan Kistler for The History Channel, three rules in The Code dealt with how sex and love were to be portrayed:

• “Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at or portrayed. Violent love scenes, as well as sexual abnormalities, are unacceptable.”

• “The treatment of love-romance stories shall emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.”

• “Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.”

Ultimately, things such as “sex perversion” fell in the purview of the Comics Code Authority Administrator or whoever it was working at the office. There were no written rules or guidelines or definitions. All in all, these three rules kept LGBTQ characters out of mainstream comics for the longest time. In the same year (1954), DC introduced Catwoman as a potential love interest for Bruce Wayne (Batman), probably as an attempt to silence Wertham’s accusations that Batman and Robin were romantically involved. However, according to The Code, Catwoman was not a suitable love interest for Batman since she was a criminal. Catwoman was dropped, kept obscure but reintroduced once again as the main character 12 years later in 1966.

Also read: Mercury poisoning has Sholakili, the pride of Kodaikanal, at risk

Several of The Code’s guidelines were revised in 1971, and then again in 1989—which is when it finally dropped its rules against LGBT content. It finally ceased to exist at the turn of the 20th century. Fast forward to an openly bisexual Superman, an openly bisexual Robin, a gender-fluid Deadpool and Loki, and villains such as Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy who are in non-monogamous romantic relationships, and you will see that gender coding in comic books has always been evolving. Comics and their representative superheroes have always been either male or female, but over the years, as we globally moved the conversation towards gender, we have seen this echo and reflect in comic books as well as superhero films.

Superman coming out as bisexual—and kissing his male friend on the mouth in artwork from the upcoming issue—does not hold the same shock value as it probably would in the 1930s, yet, at the same time, also brings to light the importance of having characters that ALL of us can relate to.

“The idea of replacing Clark Kent with another straight white savior felt like a missed opportunity,” says Tom Taylor, the series writer for “Superman: Son of Kal-El,” in an interview. “I’ve always said everyone needs heroes and everyone deserves to see themselves in their heroes and I’m very grateful DC and Warner Bros share this idea. Superman’s symbol has always stood for hope, for truth, and for justice. Today, that symbol represents something more. Today, more people can see themselves in the most powerful superhero in comics.”

However, the comic industry’s pragmatism and attempt at inclusivity can be questioned by asking one simple question: Why can’t creators come up with a new superhero that represents the LGBTQ+ community instead of bending an old character to fit a new gender role? Wouldn’t that be truly representative of the community?