Riyas Komu interview: How art can be a site of political discourse, dissent

A 90 x 83 × 23-inches wall, made out of recycled wood, metal and automotive paint, stands tall at a corner of The Guild gallery’s booth at the 2023 India Art Fair (IAF). The fair’s custom-built tent, spread across over 20,000 sq. metres at the NSIC Ground in Delhi, is the epicentre of the usual hustle and bustle IAF — arguably the largest showcase of modern and contemporary art from South Asia — has come to be associated with. As waves of people trickle in, some swarm around the wall, frenetically capturing it on their cellphone cameras.

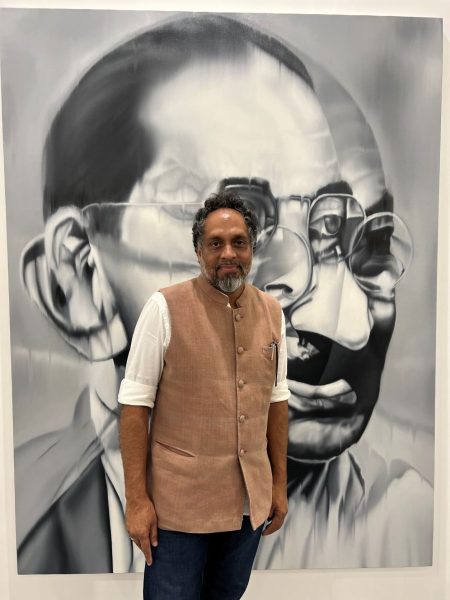

Titled Salabhanjika and the Wall — I (2023), the wooden wall is an installation by Mumbai-based artist Riyas Komu, whose works are laden with political overtones. Like the heterogeneous artworks on display at the fair, the hordes of men and women walking in are diverse. “This is India. Look at their curiosity, passion, commitment and interest,” says Komu, a multimedia artist and curator. Sitting in a chair a few steps away from the wall at the booth’s entrance, he can’t help but marvel at the infectious energy radiating from the crowd.

There is another aspect about the fair that elates Komu: its character, like film and literary festivals around the country, as a secular site for the celebration of arts. “This is a unique sight. Being an Indian artist, I feel excited to see crowds coming without any inhibition to get charged up, to see multiple creative expressions across diverse mediums and materials, to revel in the contemporariness of art,” says Komu, whose practice as an artist traverses a gamut of mediums, including sculpture and photography, materials (canvas, wood, ceramic and terracotta) and techniques (woodcut, etching, photography and videography). Whatever the medium and the material, art has been Komu’s mind-field where he lets his imagination set sail to explore the links between past and present, faith and fundamentalism, society and polity.

Wall as a metaphor for exclusion

Salabhanjika, a Sanskrit word, is a blend of sala (tree, enclosure or wall) and bhanjika (breaking or interrupting). In Indian sculpture, Salabhanjikas symbolise the idea of women and fertility and have often been portrayed as a stylised feminine figure either standing near a tree or clasping its branches. Komu’s Salabhanjika and the Wall — I, a politically charged work, is a take on multiple historic moments of India. For him, it’s a project through which he wants to reflect on the Indian Constitution and its certain narratives, starting with the first illustration in the handmade version by Nandlal Bose and Prem Behari Narain Raizada to the last image that depict Indian culture and heritage. Bose, one of the pioneers of modern nationalist art, and his fellow artists from Santiniketan were entrusted with embellishing the original manuscript of the Indian Constitution with twenty-two unique illustrations.

Also read: How SH Raza and Progressive Artists’ Group put India on international art map

“When you go through the illustrated Indian Constitution, you notice that it celebrates India’s diversity and multiculturalism in a certain linear narrative,” says Komu, who makes the Salabhanjika and the Wall series a repository of the civilisational depth and diversity: the two sides of the wall span the 5,000-plus years of the Indus Valley Civilisation. While on one end are the Harappan motifs, forms and figurations, on the other, there is the linocut print (the portrait by Bose) of Mahatma Gandhi walking during the Dandi March, riddled with three bullets shot by Nathuram Godse. The three bullet marks are visible on the other side of the wall with Indus Valley seals. “Those three bullets were a hit on our civilization,” says Komu, who considers Gandhi, the Father of the Nation, as a figure who epitomised Indian culture and the tradition of tolerance.

For Komu, who keeps revisiting the Indian Constitution as a work of art, it’s not just a document that lays down the framework of India as a sovereign, socialist, secular and democratic republic but also one that celebrates its cultural wealth through symbols harking back to the richness of its glorious past. In his recent works, he looks at the Constitution with a different, novel perspective. They are in continuation of the narrative in India’s supreme law book that refers to India’s history and its knowledge systems: arts, literature and poetry. Salabhanjika is one of the many illustrations in the calligraphed Constitution, which include one of Chandragupta Vikramaditya, the third ruler of the Gupta Empire (4th-6th CE); the reign of the Gupta dynasty was believed to be the Golden Age during which there was tremendous advancement in arts, mathematics, science, literature and philosophy.

The wall also becomes a metaphor for the politics of exclusion and discrimination against the marginalised communities, including minorities. The contribution of art in the making of the Constitution has been Komu’s preoccupation for a while. His explorations into the structure of the Indian Constitution reflects a revivalist tradition. In the project he is currently engaged with, he is trying to make the illustrations much more inclusive. “I am reworking and looking at many possible inclusions which I can bring into,” he says.

The metaphor had earlier surfaced in his 2013 work, The Last Wall (a video film about a lunatic). The 13-minutes-long film is based on graffiti made by a lunatic on the street wall where the artist lives and archives the society. “Wall refers to divisive politics contaminating the society, sowing seeds of alienation and it also evokes colonial memories. The wall is a site of expression, but it has also been a site of divisions and conflict,” says Komu.

Nationalism, identity and citizenship

Also on display at the fair was Komu’s other work that draws on the historical and political figures. In Dhamma Swaraj-post scriptum-2022 (oil on canvas), an image of a bespectacled Gandhi morphs into that of a bespectacled Bhimrao Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian Constitution. At a time when the Constitution is under constant threat, Komu juxtaposes the two images against the fading visuals of the Preamble as well as those depicting violence and fear. Dhamma Swaraj-2017 a triptych was part of Komu’s solo show, titled ‘Holy Shiver’ at the Art Alive Gallery in New Delhi in 2018, which documented an artist’s response to the Indian state’s deliberate conflict with its founding principles.

Also read: I come from an orphaned city, with a murdered background: Asmaa Azaizeh

Last year, one of Komu’s recent installations, Salt & Pepper (Sculpture-II), made using the same material as Salabhanjika and the Wall I does, was on display at a group show in Delhi. Drawing on the wellspring of history and memory, it celebrates Gandhi’s political act of walking. “The gesture of walking represents the forward force of freedom which resonates with many iconic and resurgent moments in India’s search for identity, struggles for independence and expressions of dissent. Walking was a symbolic act and evocative metaphor that reimagined the destiny of a people by way of defiance and disobedience. The striding image, walking out of oppressive structures and walking towards freedom and truth is an invocation to those unforgettable flights of intensity in our history; those moments of departures that have always inspired our political imagination and fired our dreams of freedom,” read the curatorial note.

In late 2019, Komu had a show, “Out of Place”, at Gallery Sumukha in Bengaluru. The series of works on display drew on shared history, heritage and lineage. In recent years, there have been systematic attempts to erase and obliterate certain parts of the past. Through replicating and reconfiguring archival images and the symbols of the past, including Asoka pillar, Dandi Bridge and Gandhi’s stick, among others, Komu underlines their significance, hinting at the sheer impossibility of erasing history that has become part of our collective consciousness. There were familiar nods to the raging issues of nationalism, identity and citizenship — evident in some works, oblique in others.

‘Political art comes organically’

Komu was born in Kerala, in Thrissur’s Ettumana village. His father, M. M. Komu, was a political and a true blue Gandhian who wore socialism on his sleeve. He also ran a matchbox factory, where Komu had his early trysts with what became his favourite medium in later years: wood. “I have a material connection with the wood,” says Komu, who arrived in Bombay, where he has lived ever since, at the age of 21. It was in 1992 that he had joined JJ School of Art. The bloody aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition turned his city, and many other parts of India, into a communal tinderbox.

As the rath rolled and India burned, it left a deep impact on the young artist; he started responding to the cataclysms of history through his art. His response to the 2008 Mumbai terror attack was Last Pass, a wooden sculpture with four strong feet holding a massive coffin, hinting at the death’s seizure of the living. After 9/11, he came up with Tragedy of a Carpenter’s Son III. A huge wooden plane, marked with the prayer Muslims recite before embarking on a journey, seemed to blur the line between faith and fundamentalism.

Corpses and tombs are recurring motifs in Komu’s universe, a strand that is reflected in his early works, from A Worthy Product Damaged by Their Brain (1998), a painting in which a corpse lies beneath a painting of Vincent van Gogh to Undertakers (2007), an installation with a series of wooden tombstones. In one of his best-known works in the following decade, Designated March by A Petrol Angel (oil on canvas) — exhibited at the 52nd Venice Biennale, curated by Robert Storr — he created a series of portraits of a woman wearing a headscarf to pay his tribute to the resilience and resolve of the Iranian women. He represented the Iranian Pavilion during the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015 through another installation titled Fragrance of Funeral.

Political art comes organically to Komu. “I’d always experienced a kind of cosmopolitanism at home. My political art practice is a way of continuing the legacy of a family I was born into: a family which had the room for multiple cultural assimilations. Whatever I have tried to do through art, the primary investment I have put into my art practice is the idea of diversity,” says the co-founder of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, for whom everything revolves around celebrating the idea of diversity and multiculturalism. “This is not something you’re doing forcefully, it’s part of your genes,” he adds.

Art as an archive of our times

Komu, a thinker and an archivist, believes in creating art that mirrors the times. To him, art is a site of knowledge and not just of aesthetic fulfilment — it’s a site to explore creative ideas or abstractions that also becomes a conduit to narratives and storytelling: “I’m very much interested in India’s modernist history. In the last 100 years, the investment that we have made to build this nation is inspiring. I’m interested in looking at art as a site of knowledge, conversations and discourse; in the new ideas of humanism and the new discourse in art, literature and cinema brought about by the evolution in technology.”

Art is also about creating an avenue for dissent and discourse. In a country with a dearth of cultural spaces, he is keen on creating a space where art production is taken seriously. This quest is also in sync with his innate nature: “I am interested in living a life which is compassionate; I am interested in sharing ideas and working for a common cause. I try to be as truthful to the world as much as to the art.”

The oceanic imagination

One of Komu’s ongoing projects is Sea: A Boiling Vessel, which is being held at Kashi Hallegua Art Gallery in Mattancherry, Kerala. Presented by Cochin-based art collective, Aazhi Archives and Design Trust of India, the multidisciplinary show, which brings together 20 artists, academics, and performers, explores Kerala’s hidden pasts and fluid futures. Its wide arc includes studies around the Indian Ocean, maritime culture, climate concerns, coastal erosion, Kerala’s cultural heritage and migration histories.

The show, curated by Komu, opened on December 13, 2022, and will continue till April 30. “It looks at multiculturalism and diversity. That’s the spirit of art-making that we all need today. We have knowledge systems that we can cherish and excel with,” he says. There is a photography project that looks at the post-oil boom history of the Middle East through the albums of Malayali migrants from the early 1950s. Also few music projects celebrating history and a very special multi-lingual Lullaby Project celebrates India’s multicultural fabric.

Politically, Komu likes branching out. While our art discourse takes place in the terrestrial imagination, Komu is trying to develop a new discourse through the oceanic imagination. “Gandhi walked miles and miles as the first protest against the coloniser. When he touched the salt water, he was not just touching it to lift the salt. To me, it was very symbolic, akin to feeling our ancestors. This gives you a lot of power,” says Komu. He is currently at the sea, both literally and metaphorically, trying to think through water: “Our ancestry lies in the sea. Many of our civilisations and cultures flourished through water. Water is a carrier of conflicts, but it’s also a site of refuge.”

Working on his latest project has unravelled a sea of symbolism that Komu would like to work on later, rearticulating certain historic perspectives in the same fashion he has done before. He has, for instance, always wondered how to look at Gandhi’s salt march from a different perspective. He may already have had an epiphany.