Poet in exile, opium, a stolen manuscript: Va Ra's biography has it all

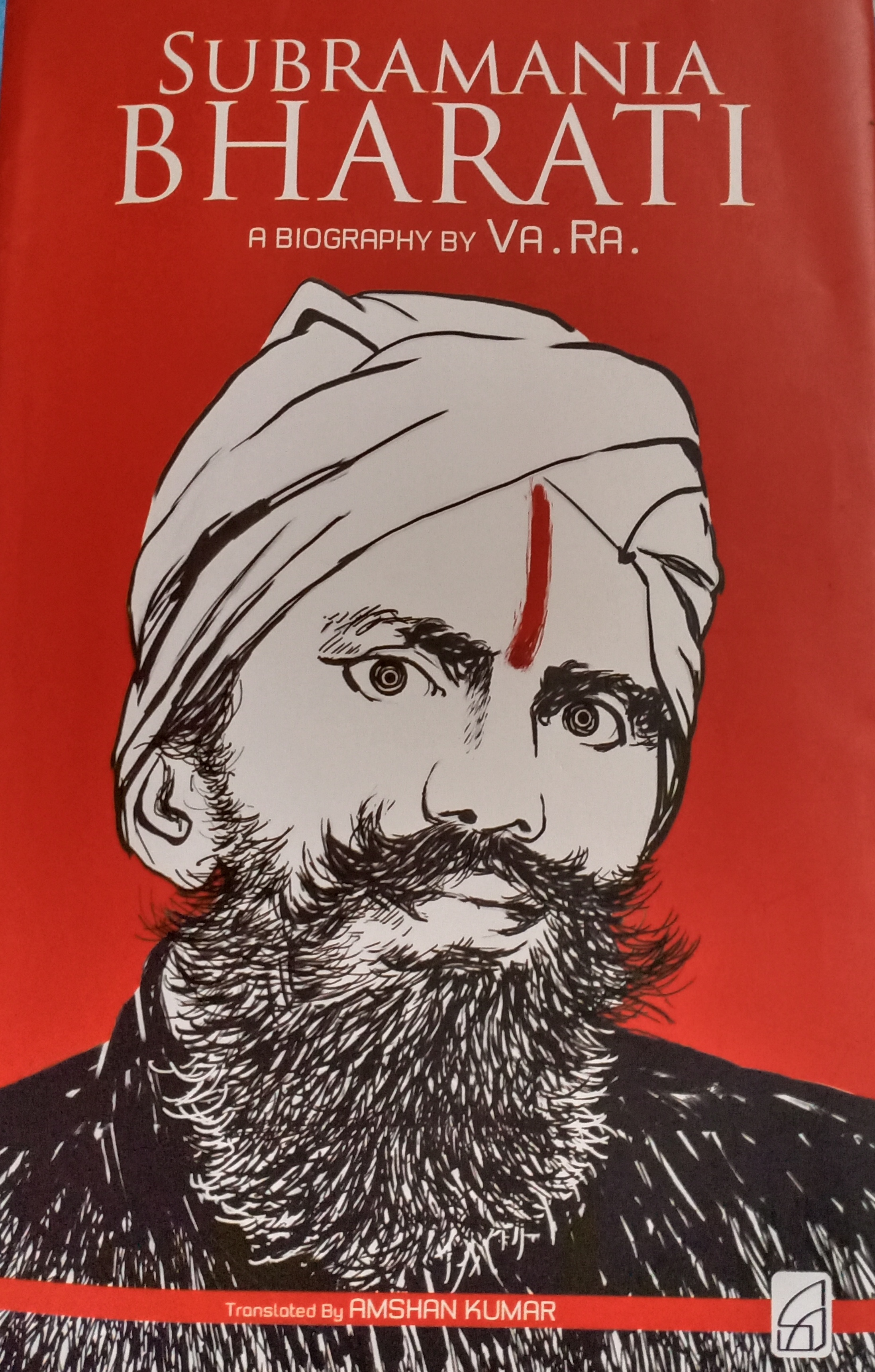

A clean moustache, neither sharp like Kaiser’s nor a neatly trimmed one. A bindi like a full moon on the middle of his forehead, he would wear a banian and a buttonless shirt at times. A coat over that would have only a single button fastened for the sake of appearance.

A clean moustache, neither sharp like Kaiser’s nor a neatly trimmed one. A bindi like a full moon on the middle of his forehead, he would wear a banian and a buttonless shirt at times. A coat over that would have only a single button fastened for the sake of appearance.

On the left side of the buttonhole, he would insert a flower (a rose or a jasmine) bunch. On his left hand, one can find a notebook, a few papers and a Perumal Chetty brand pencil in his coat pocket. “He always used a pencil and I never saw him write with a pen,” writes Varadarajan Ramaswamy (Va Ra), a prolific writer and one of the founders of the Manikodi literary journal, in his biography titled Mahakavi Bharatiyar.

The biography attained significance when it was published in 1944 mainly because it gives a fair account of the life of Bharati who Va Ra first met in 1911 when he (Bharati) was in a self-imposed exile in today’s Puducherry. (Subramania Bharati left Madras for today’s Puducherry in 1908 and remained there till 1918, to avoid arrest from the British government. Since Puducherry was under the control of the French East India Company, he lived there in self-imposed exile for a decade. It was during this time he wrote his great poems such as Kuyil, Kannan Pattu, Panchali Sabatham.)

Also read: New York Times’ 100 Notable Books features 3 Indian writers this year

Even though many have written about Bharati, the biography of the great poet written by Va Ra still stands the test of time, as it reveals the poet’s character and the times he lived in. It also clears many misunderstandings among people about Bharati.

Award-winning filmmaker and scholar Amshan Kumar has translated the biography into English titled Subramania Bharati (published by Sol Aer Pathippagam) with an introduction and notes. It was while making a documentary on Bharati in the late 1990s that Amshan Kumar had first heard about Va Ra’s biography of Bharati.

“Eight months ago, when l learnt that the book had not been translated into English, I thought of doing it. It was challenging, mainly because some usages needed proper research and reference,” says Amshan Kumar, whose feature films Oruththi and Manusangada won accolades.

It was after declaration of the first lockdown on March 24, 2020 that Amshan Kumar started working on the translation. “Va Ra was a great writer and scholar who played a significant role in making Bharati’s works known nationally. I believe that Va Ra’s biography didn’t get the importance that it deserves. I translated it into English mainly to get the attention that it deserves,” he says.

Also read: Bagmati river causes floods, but farmers don’t mind it

In 1911, Va Ra was sent to Puducherry as an envoy to meet Aurobindo Ghosh by Kodiyalam V Rangasamy Iyengar, a member of the British Council of State in Delhi, who was secretly helping the patriots. Aurobindo was in Puducherry after he had been acquitted in the Alipore Bomb Case. Since Va Ra didn’t know much of Aurobindo, he went straight to Bharati’s house, mainly because he had read Bharati’s patriotic songs and other works.

Even though Bharati had a good command over English, he could not see it as a language without associating it with the British government. To introduce himself to Bharati, Va Ra chose English which naturally didn’t go well with the poet.

“For how long Tamils should choose to talk in English among themselves?” Bharati asked Va Ra in a sad tone. He then sang a song called Maravan Pattu (Song of Maravan) and Va Ra felt himself transported to another realm altogether. As days passed, Va Ra started following Bharati’s everyday life closely with people around him.

Bharati was fond of wearing the turban like the Sikhs. “With that headgear if he spoke in Hindi, none would mistake him for a Tamil since his diction was flawless,” writes Va Ra, who also noticed that Bharati could not put his left foot down with ease. “There was a corn of the size of a big coin on the sole of his left foot. If by chance he happened to press his left foot against any hard object, he would sit down writhing in pain.”

Also read: Vandana Kohli’s ‘Hinge’ helps you keep a tryst with your inner self

Was Bharati a Vedantist? Many, taking advantage of Bharati’s spiritual leanings, say ‘yes’. Bharati, however, was not a sham Vendantist, according to Va Ra. “To call Bharati a Vedantist is a blunder,” according to Va Ra. “If he (Bharati) were to ask a boon to live forever he would do so only to live on earth with pride. He fiercely opposed slothful men who prayed to attain heavenly good faster,” he writes.

Subramania Bharati was born in 1882 in Ettayapuram in Tirunelveli district. Being a big province, Ettayapuram’s Zamindar had its title as “Raja”. As a boy, Bharati enjoyed more privileges in the Ettayapuram palace. Since he was close to the Zamindar, the Vidhwans and others showed him love and respect. The title ‘Bharati’ was conferred on him at the age of 11 by Sivagnana Yogi, a Tamil savant, in the Ettayapuram Samasthan.

In Puducherry, Bharati, according to Va Ra, kept himself away from the habit of taking opium, a habit that he came into contact with when he was with the Raja of Ettayapuram. “During the stay in Puducherry for the first three-four years until 1911, the thought of opium never crossed his mind. Instead he would lodge a whole nutmeg in a corner of his mouth and enjoy its saliva secretion,” writes Va Ra.

One day before taking a bath, Bharati gave Va Ra a big nutmeg and asked him to chew on it. Va Ra felt like levitating and his legs began to totter even though he had eaten only half of it. Va Ra never knew Bharati consumed opium until one day he asked his disciple in coded language, “Bring me the materials for the sacred fire.”

“None of us dared to tell him ‘you should give up that habit.’ But opium addiction gradually ruined his health, he writes. However, Va Ra was not clear why Bharati revived his opium addiction while staying in Puducherry.

Bharati donated money and his dresses to the pushcart drivers of Puducherry. He never bothered to save money. So his life was always filled with commotions and amid all the chaos one day he suffered a huge loss. The manuscript of Chinna Sanakaran Kathai’ that he almost finished writing disappeared from his shelf.

According to Va Ra, Bharati thought Chinna Sankaran Kathai had finally reached the secret police, but it was not through his domestic help Murugesan. “But we did not think in two ways like Bharati,” writes Va Ra. Even though Va Ra and others requested Bharati to write it again, he wrote only six chapters and then he said his mind was not on it. Bharati never spoke about it later.

Bharati was fond of playing cards and chess but he was not proficient in either. But he was particular about his moustache. Va Ra said he found Bharati without his moustache only once. Bharati had a bad habit of spitting and it would fall on the floor of the house as ordained. “We never liked that habit of his but we lacked the courage to point it out to him,” writes Va Ra.

When Mahatma Gandhi came to Chennai in February 1919, many wanted him to lead the protest against the repressive Rowlatt Act. Bharati’s meeting with Gandhi in 1919 was significant. “Bharati and Mahatma met and talked. In just one meeting, they understood each other very well,” learns Va Ra.