Of veins, ink and fire: Kochi-Muziris Biennale’s fifth edition curates resistance

“Some stones heaped aimlessly, a broken cot, an abandoned boat, some damaged kitchen utensils, walls full of unfathomable ‘modern art’, and a number of good-for-nothing intellectuals wandering the streets of Fort Kochi and Mattancherry — this is what the state government spends a lot of money from the public exchequer for, in the name of God-knows- what, biennale affair.”

This is roughly how a Malayalam newspaper presented the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) a decade ago, when it started first in 2012. From this philistine description by a cynical journalist, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale has come a long way to its fifth edition titled, In our Veins Flow Ink and Fire. Curated by Singapore-based artist Shubigi Rao, it has been attracting thousands of art lovers from across the globe. The biennale, back after a four-year hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with 88 artists from around the world, appears to be evidence of a politically charged resilience of the human spirit this time.

It’s been a true celebration of contemporary political art, featuring installations on the past and futuristic visions, visual narratives, live music, interesting talks, and other captivating artistic performances.

According to Bose Krishnamachari, the president of the Kochi Biennale foundation, aesthetics can be taught by making sights and creating foresights. “This event became people’s biennale because we managed to erase the borders of ‘white cubian’ gallery system or elitism,” Krishnamachari tells The Federal.

In Our Veins Flow Ink and Fire

“To envision this biennale as a persistent yet unpredictable murmuration in the face of capriciousness and volatility comes from my unshakeable conviction in the power of storytelling as strategy, of the transgressive potency of ink, and transformative fire of satire and humour. What do we find when we listen, read, record, think and make? For one, that even the most solitary of journeys is not one of isolation, but drinks deeply from that common wellspring of collective knowledge and ideas. Even when we work alone, we amplify the voices of others, and this form of sociability is why when we create, we are collective,” reads the curatorial note of the fifth edition of the biennale.

Also read: Mathrubhumi lit fest: In Kerala, a literature event seeks light of ideas for future

“When you walk through the Aspinwall house, Pepper house and The Anand Warehouse — the main venues of the biennale — you will see the works not just in isolation from each other, but actually speaking to each other. None of us exist in isolation. When we write, think, make or speak, we are unconsciously drawing on the words of others. There is no such thing as a lone genius. That’s a myth. We are all part of a collective action, collective thinking. When you see this exhibition, I want you to not only see an artist working, but also think about the milieu,” says Shubigi Rao, the curator. “It’s not important to always fill in every gap. You should intellectually or imaginatively collide with the art works and find a way to spend time with them,” adds Rao.

“This location has got a character: this architectural and heritage space and the spice trade have given so many layers of history and culture that come from different parts of the world and that confluence and that melting pot of cosmopolitanism have given us confidence for the project,” says Krishnamachari.

Richard Bell: The man, the rebel and, above all, the Aboriginal

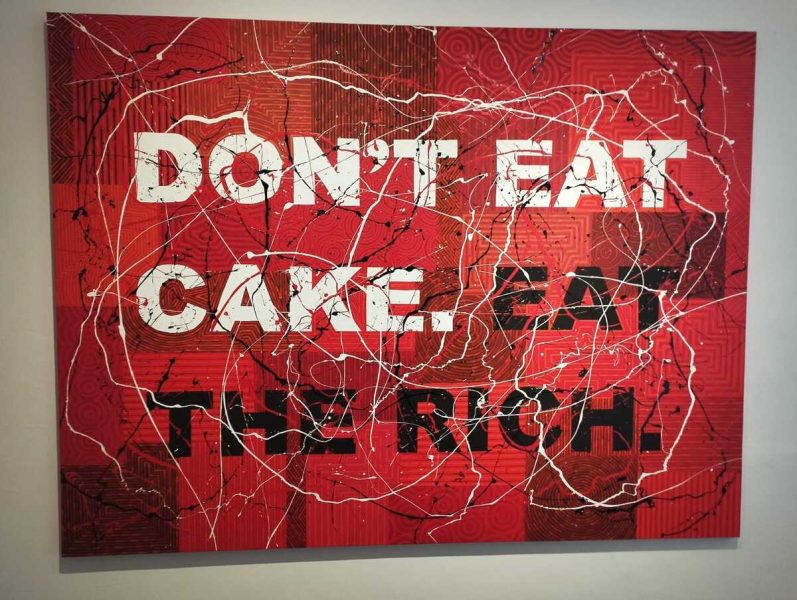

This edition of the biennale welcomes us with a sizable khaki tent, ‘Embassy,’ by the Australian aboriginal artist Richard Bell in the middle courtyard of the Aspinwall house. It’s erected as a tribute to Aboriginal tent embassy, which was first set up in 1972 in Canberra to denounce the McMahon Liberal government’s denial of Aboriginal land rights in Australia. Bell’s ‘Embassy’ was pitched during the 2016 Sydney biennale and the Venice biennale in 2019, where he staged a protest after being rejected to enrol as Australia’s official artist. Inside the hall we have his magnificently coloured and sloganized canvases with politically overt black and white letters in artistic red background, reading ‘DON’T EAT CAKE, EAT THE RICH’ and another one with “White Privilege is Affirmative Action for White People.”

Bell had boldly declared ‘Australian Art It’s An Aboriginal thing’. His artwork is one of the main attractions of this edition of the KMB. ‘Bell’s Aboriginal Embassy is a powerful political work, so much to take away,” says Jefferson Hack, an international art curator from Montevideo, Uruguay, and the CEO of Dazed Media, who was overwhelmed by the atmosphere here. “The exhibition is too heavy and highly political which forces me to come back again,” says the South American.

The Cycling Rap of Martta Tuomaala

Finnish multidisciplinary artist Martta Tuomaala’s video installation featuring herself is another stunningly political work on display. “Welcome to this 45-minute indoor cycling class, my name is Martta. This is a steady-state cardio class, so no breaks, but no high intensity spurts either. You should be able to talk, or even sing along, without feeling out of breath. Just copy what I’m doing and you should work up a sweat. This programme is called FinnCycling–Soumi–Perkele!”

This is how Martta introduces herself and her work in the video. Socially engaged art is her realm and she identifies herself as one of those left-leaning artists who ‘actively involves in various art workers’ activities and events concerning art politics.

With upbeat training rap songs playing in the background, the video presents current, social, and ecological issues related to Finland in the form of an indoor cycling class.

‘A Peal of Spring Thunder’

News photographer Ishan Tankha’s portrayal of the ‘Naxal-affected’ Bastar region is one of the significant works from India. His project, ‘A Peal of Spring Thunder’ seeks to ‘bear witness to the ebbs and flows of the life that Adivasis and Maoists experience through the manner in which they work and live in the forest and villages, interact with their surrounding urban environs as well as the ways in which they create a sense of home and place in a deeply fissured space’.

Also read: Sundance 2023: ‘Fair Play’ is a stellar, breathless indictment of the ‘nice guy’

‘It’s amazing to see the work of a photojournalist who is this much politically sensitive,’ opines Emily Castillo from Mexico, who herself is a television journalist. “Working on this kind of a project in a very unfriendly environment requires quite a conviction and the photographs really tell as much to me,” says Castillo.

“One finds the very significant presence of the ‘margins’ here: artists and resistance movements from South East Asia and also from the North-East region in India have never been represented so searingly and powerfully before. As we make our way through these works, one is brought back to one’s concrete, present in all its visceral clarity and political urgency,” says art critic and author C S Venkiteswaran.

A Personal Archive of Tibetan Resistance

‘The Shadow Circus’, a long-time project by filmmaker couple Ritu Sarin and Tensing Sonam, displays the history of Tibet’s armed struggle which got intertwined with the geopolitical complications, with the involvement of the CIA in the sixties. Sarin and Sonam are re-evaluating the audio visual archives and exhibiting a re edited version of their 1998 documentary of the same name.

“The situation in Tibet has gone from bad to worse, over the last decade. Now studying the local language or uttering the name Dalai Lama has become a crime in our land,” Tensing Sonam tells The Federal. The Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF), run by Sarin and Sonam, has also organised an independent film festival at the venue, Anand Warehouse.

“Shubigi Rao’s curation stands out in terms of the show’s political content and intent. All the works exhibited at KMB 22-23 are deeply political, dealing with the most urgent and poignant of socio-economic and geo-political crises unfolding across the world. The all-pervading themes are state oppression, displacements of various kinds and in the name of many reasons, exile — political, racial and social — forced migration, gender issues, and ecological violence. Besides, there are umpteen ways and means by which people find expressions of resistance and modes of survival and overcoming,” observes Venkiteswaran.

“I also found the exhibition layout and design very interesting: there is no clutter and the viewer is given enough physical and mental spaces between and inside the installations,” he adds.