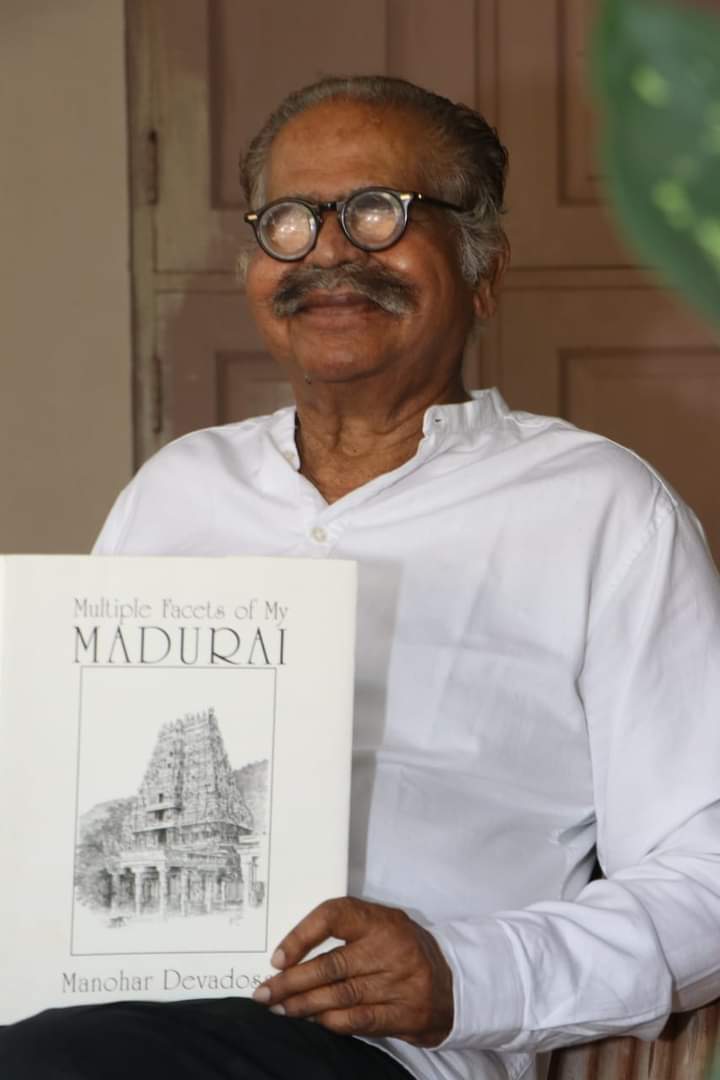

Manohar Devadoss: With his eyes and a pen, he brought Madurai to life

A born artist and a versatile writer, Manohar brought his beloved hometown Madurai to life with his books and ink-pen drawings

For many, Madurai is a land of temples. For some outsiders, it is an area reeking of caste atrocities, hate killings, and a violent public. This could be attributed to Tamil cinema’s portrayal of this ancient city as a rugged terrain with a ravaged culture. Paripadal, an ancient Tamil text, compares Madurai to a lotus flower which has a seat with a king sitting in the centre.

But, for renowned pen-and-ink artist Manohar Devadoss, the city of Madurai is “more or less square, both literally and metaphorically”.

Manohar, who passed away on December 7, will be remembered not only for his line sketches of Madurai and Madras, but also for his reflections on Madurai in his writings. He was 86, and is survived by his daughter Sujatha.

A born artist

Born on September 10, 1936 to Harry Jesudasan Masilamani and Cynthia in Madurai, Manohar was a self-taught artist. He did his schooling at Sethupathi High school, and completed his bachelor’s in Chemistry from Madurai American College in 1957.

While he was in the final year of his graduation, his father, a doctor, died due to lung cancer. Unable to take up higher studies, Manohar took a clerical job in the District Collector’s office to support his family, since his elder brother was in the middle of postgraduate studies and his younger brother was still in school.

A few months later, Manohar got an offer from Oldham’s, a British battery manufacturing company, later known as Standard Batteries, where he worked as a chemist for the next four decades and rose to the position of technical director. Meanwhile, in 1969, he went to Oberlin College in the US to study for his master’s degree, and worked as a lab instructor as part of the study for three years. After completing his studies, he returned to India.

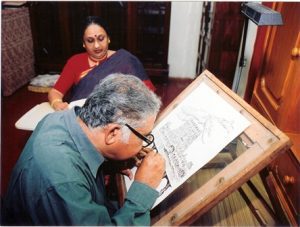

It was during his school days that Manohar discovered an innate talent. He had a photographic memory, and was able to sketch architectural drawings with a free hand just using his pen. But he treated it as a hobby, not a profession.

From an artist’s perspective

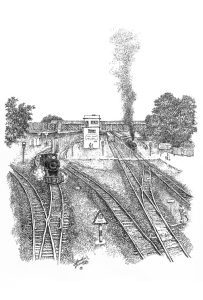

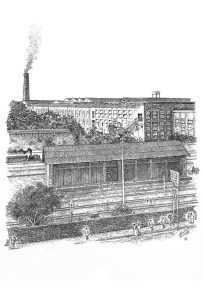

Manohar was interested in ‘perspective art’ — drawing what the eye saw. This can be understood by his own explanation about how he made a drawing of a rail engine and carriage:

“One Sunday morning, the three boys went to their favourite bridge to watch the departure of the south-bound Trivandrum Express. Before the train started, Sundar saw a lone steam engine with whiffs of smoke rising from its chimney, lightly trundling along. Sundar craned his neck as far as he could and saw the engine go by, right below them. He became quite excited with a simple idea that struck him…”

“… The next morning, he showed his sketch to his classmates and they looked blank. When he told them that it was a railway engine and enthusiastically pointed out the chimney, the roof of the driver’s cabin, and so on, his fellow students remained unconvinced. Sundar explained, ‘Obviously, how an object is represented in a drawing depends on the position from which the object is looked at. If a gramophone record is seen sideways, it’ll look like a line. So, a straight line too could represent a gramophone record.’”

This section is found in his autobiographical first novel, Green Well Years, first published in 1997. The protagonist, Sundar, is none but the author himself.

Madurai sketched with words

While Manohar enjoyed a talent he was born with, life had many setbacks in store for him. He started to lose his vision in the right eye due to retinitis pigmentosa, a rare eye disease that affects the retina, in the 1970s, when he was still in his 30s. In his left eye, he had tunnel vision.

He married Mahema, also an artist, in 1963. In 1972, a car accident left Mahema a wheelchair-bound quadriplegic. Not one to lose hope, Manohar continued to draw and write. He produced seven books, out of which two were pen-ink drawings of Madurai and Madras (now Chennai). A Poem to Courage, a sequel to Green Well Years, is unfortunately out of print now.

Of those seven books, Green Well Years has been celebrated for its revisiting of Madurai’s history that blended with a boy’s coming-of-age. The book was later translated by the author himself into Tamil as Enadhu Madurai Ninaivugal.

Forgotten places and people

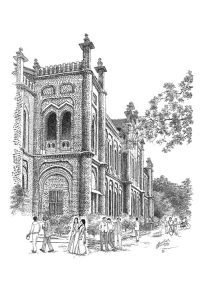

In his novels, Manohar sheds light on lesser-known places and people. Among them is Sethupathi High School, which was one of the earliest modern schools started by an Indian.

“At that time, a majority of Brahmins were literate, while most non-Brahmins were not. But doors were beginning to open for non-Brahmins as well. Enlightened Brahmins recognised the value of the more egalitarian form of education under British rule. However, they were also worried, not without reason, that such education, apart from imparting knowledge, would also popularise Christianity. They felt that the need of the hour was good schools modelled on the western system, that would impart education on the ‘right Hindu cultural lines’.

“With this view, Venkatarama Iyengar started a school in the late 1880s. This school was one of the pioneers in the region and was recognised by the government in the early 1890s. The school soon shifted to its present location, and around the turn of the century, the Raja of the neighbouring district of Ramanathapuram, Baskara Sethupathi, gave the school a donation of ₹10,000 — then a princely sum. The school was named Sethupathi School in honour of his family,” wrote Manohar.

It was Raja Baskara Sethupathi who also sponsored Swami Vivekananda’s trip to Chicago. It was in this school that poet Subramania Bharathi, who celebrates his 141st birthday this year, served as a Tamil pundit for a monthly salary of ₹17.50. It was here that the renowned singer MS Subbulakshmi gave her maiden performance.

Anglo-Indians and Sourashtrians

Due to the influence of movies set in Madurai that show excessive violence, most outsiders assume people hailing from the region to be illiterate and gullible villagers. But, in reality, the city is a major cultural and education centre, which the films shut out. The city also hosts a considerable population of Anglo-Indians and Sourashtrians, who are again blacked out by Kollywood.

The only Tamil film that showed an Anglo-Indian colony in Madurai was Vetri Maran’s Aadukalam (2011), which again had its share of violence.

Writing about the Anglo-Indians, Manohar observed that they excelled in sports and education, which resulted in them ‘virtually running’ the behemoth Indian Railways. Nearly every engine driver, fireman, guard, station master, and line inspector came from this community. “Consequently, near every large railway junction, there sprouted communities of Anglo-Indians,” he wrote.

“Buffeted between the class-conscious white community on the one side and the caste-ridden Indian society on the other, the Anglo-Indians became acutely conscious of their mixed blood. The rigid caste system of the Hindu social order did not allow them even a sporting chance to identify themselves with the natives.

So, the Anglo-Indians adopted British customs with an avidity bordering on obsession. They went to the extent of referring to the British Isles as ‘ome’ (home) and tended to live beyond their means,” he said.

Likewise, while writing about the Sourashtrians — traditional weavers from Gujarat who shifted to Madurai during the time of the Nayaks, and are commonly known in Madurai as pattu nool kaarar (‘silk thread people’), Manohar said “they lived amicably with the local Tamils, but unlike the Telugus, they were rather aloof and kept to themselves”.

On temples, dams and rivers

Manohar also spoke about the beauty of the Meenakshi Amman temple, River Vaigai, the impact of the Periyar Dam on the surroundings, how Harvey Mills brought a change in the lives of the people, the grandeur of American College, and the movie theatres that showcased Hollywood and Bollywood movies, among others. His autobiographical book is peppered with such history, and it could be a guide for those who wish to know about Madurai, and a recollection tool for people who hail from the city.

Besides being a talented artist and a good writer, Manohar was also an empathetic human being. Following his wife’s death in 2007, he set up a trust named Mahema Devadoss Endowment Fund at Aravind Eye Hospital to support treatable blindness among the rural population.