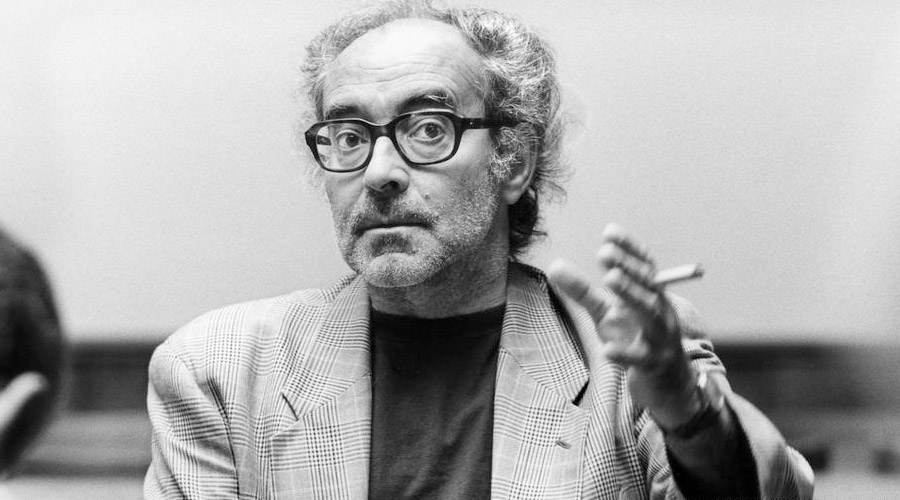

Jean-Luc Godard: An auteur and provocateur, adrift in the cosmos

‘I am a painter with letters. I want to restore everything, mix everything up and say everything.’ This is how French-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard (1930-2022), the mercurial pioneer of the French New Wave, described himself once. The director, who endeavoured to find the audience for his films on his own terms during various stages of his career, choreographed his exit from the world’s stage on Tuesday; he ended his life through assisted suicide at his home in Rolle, a sedate town on Lake Geneva in Switzerland, where he had lived and worked for nearly five decades. At 91, perhaps he had come to realise that he had mixed enough things up, and had said everything that he wanted to say.

As an auteur and a provocateur, and as an artist and an innovator, Godard blazed a trail with his films. He was both revered and reviled for crossing the cinematic boundaries and breaking conventions, but the style of filmmaking — in his essay films shot with handheld camera, incessant collages unravel in a way that catapult the action from one image to another, with jump cuts leaving no room for smooth transitions — resonated with Hollywood iconoclasts like Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino as well as scores of others around the world, including Satyajit Ray.

The Disorder of Things

A movie, according to Godard, “should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.” Preoccupied with the idea of upsetting the order of things, Godard believed that stories gave form to the reality of the world, which sometimes was too complex to fit into a formal mould of storytelling. Therefore, he felt impelled to find a radical way, which also allowed him to explore what cinema was and how it related to life. Born in Paris, he had become a citizen of Switzerland when his parents migrated in his infancy. Since his mother’s family lived in Paris, it became Godard’s creative cradle. In the late 1940s, he became a regular patron at the Paris Cinematheque and various Left Bank film clubs. His meeting with Andre Bazin, the editor of the journal Cahiers du cinema, gave shape to his early career as maître à penser — a theorist, a critic, and an experimentalist. He also met four filmmakers — Francois Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, and Eric Rohmer — who later joined him as core members of the New Wave group.

In his camera-stylo or “camera pen” concept, French critic Alexandre Astruc suggested that filmmakers should use their equipment as spontaneously, flexibly, and personally as a writer uses a pen. Using his camera as a pen, Godard began to intertwine the ideals of filmmaking with his lived realities, which changed the nature of cinema. Unlike the filmmakers before him, which included the likes of D. W. Griffith — who had expanded the art of editing and narrative films — Godard’s work shifted fluidly from fiction to documentary, and from criticism to art. Explicit references to the physical processes of filmmaking, thus, became central to his work — it’s an element which is both reflective and reflexive.

Films As Avenues For Personal Expression

Godard’s career as a filmmaker went through several stages. He exploded on the scene with his debut feature, À bout de soufflé (Breathless, 1960), a crime drama written by François Truffaut, which was intended to shake up the audience with unconventional editing and multiple jump cuts that kept jolting them from one scene to another. Godard’s most influential and commercially successful films came out in the 1960s: They included Vivre Sa Vie (My Life to Live), Pierrot le Fou, Two or Three Things I Know About Her and Weekend.

The revolutionary New Wave movement phase was followed by political experimentation during the late 1960s and 1970s when he switched to directing films that were steeped in leftist, anti-war politics. This was an introspective period in which he explored issues of spirituality, sexuality, employing the aesthetics of sound, image, and montage. Later, he returned to a more commercial mainstream. Godard’s recent works— Goodbye to Language (2014) and The Image Book (2018) — were allusive and experimental, which left a swathe of cinephiles exasperated with his style, shrinking the base of his admirers.

To Godard, filmmaking was an avenue for personal expression. Like the young critics-turned-directors of the New Wave group, he rescued cinema from the tired cliches and studio-bound artifices that had come to characterise the mainstream entertainment films. Unlike their Italian contemporaries, Godard became the advocate of a brash cinematic articulation, which played with framing, texture, editing, rhythm and backgrounds.

Gone Astray in the Cosmos?

Godard’s later political films like Le Gai Savoir (1968), consisting of political dialogues between two young Maoists, proved to be the last straw for Godard skeptics, who were getting impatient with the filmmaker revisiting the issues that had defined 1960s. For many of his sympathizers, who got alienated with the sociocultural critiques, it was the end of the road. Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, his most famous critic, one said in an interview: “I’ve never gotten anything out of (Godard’s) movies. They have felt constructed, faux intellectual and completely dead. Cinematographically uninteresting and infinitely boring.”

Godard, however, was a work in progress. In the titles and subtitles of his films, he gave us a sense of his uncertainties, drawing us to the modesty of his cinematic ambitions. Pierrot le fou (1965) is “not really a film. It is rather an attempt at cinema.” A Married Woman is “fragments of a film shot in 1964.” La Chinoise (1967) is “a film in the process of making itself.” Weekend is “a film found on a scrapheap” and “a film gone astray in the cosmos.” Instead of presenting an all-encompassing narrative, Masculine/Feminine presents “15 precise acts.” King Lear is “a film shot in the back.” Two or Three Things I Know about Her, Godard wrote in 1967, “isn’t a film, it’s an attempt at film and is presented as such.”

When he was a boy, Godard was fond of cooking up tales to excuse the mischief he often got into. His relatives and teachers would invariably tell him to be more responsible and not make up stories. As a filmmaker, who was extremely fond of using cinema as a philosophical tool rather than an entertainment machine, his producers would invariably implore him to be more responsible and make up stories. Living with this irony all his life, Godard made up stories — and also invented new ways to tell them.