How Patrick French chronicled India story, from Independence to economic progress

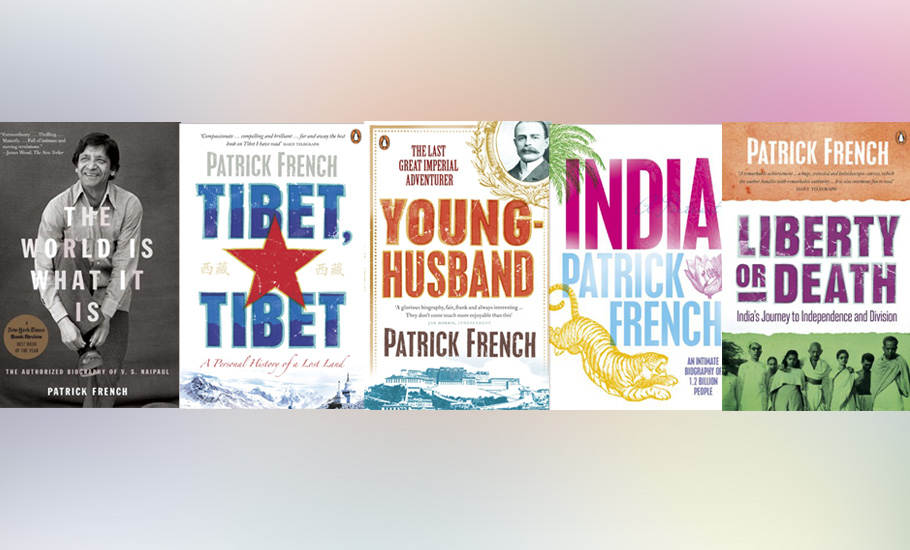

Patrick French (1966-2023), who died on Thursday at the age of 57, saw India as a macrocosm which had the potential to be the world’s default setting for the future. As a historian, he delved into the India story, from the struggle for independence and bloodied Partition to its emergence as a liberalised economy after 1991, and its subsequent trysts with economic progress. His two notable books on India — Liberty Or Death: India’s Journey to Independence and Division (1997) and India: A Portrait (2011) — chronicle the country’s resonances at key points in its history. They are rich with his grasp of India’s social, political and economic frailties and fault lines, its complexities and contradictions.

In both these books, he combines his extensive research — which entailed approaching the past through mounds of documents and multiple dignitaries — with his encounters with people, and accounts of travels across India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. French had made a conscious decision not to write bureaucrat’s history. Instead, he wrote living, human history that has people of the subcontinent running through its veins. This was not because, as he writes in Liberty Or Death, these people were the makers of political history, but because in the end, it is individuals and families who are affected by the choices that politicians make: ‘They are the one who win, or lose.’

Transfer of power and freedom at midnight

Liberty Or Death draws on the 12-volume Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: The Transfer of Power, 1942-1947 as well as the public and judicial documents that were part of the archives of Indian Political Intelligence, an organisation within the India Office in London, which was founded before the First World War to monitor activities undermining the British government of India, and folded up in 1947. Its files were locked away for nearly a century and were declassified in 1997, the year French published his first India book, after he urged the Foreign Office to review their status.

Also read: British writer and historian Patrick French dies of cancer at 57

Trawling through these documents, French came to the conclusion that the British had not decided to quit India out of any altruistic motive or strategic planning. The departure of the British from India, French writes, was also not the ‘logical culmination of a policy of benign imperial stewardship, like a kindly parent allowing a child to ride its bicycle unassisted from the moment it learned to pedal’. It was also not the inevitable consequence of socio-political forces rising up as one against the might of the colonial master and marching to demand freedom from the imperial yoke. “For many Indians, especially in the south, the deals sewn up by English-speakers in New Delhi in the 1940s were of distant importance,” writes French.

Why and how did the British leave India then? French tells us that it was because the British ‘lost control over crucial areas of the administration, and lacked the will and the financial or military ability to recover that control’. The documents of the last years of the Indian Empire French had accessed provided ‘an unexpected tale of confusion, human frailty and neglect’ — from the flaws of the then British PM Winston Churchill’s wartime India policy to the feebleness of the post-war government led by his successor Clement Attlee.

“Many of the key events of the 1940s were the result of chance, or even of error, and some of the most important decisions of the period were made on an almost random basis. Nor was there any inevitability about the fact that the Indian Empire was dissected and partitioned, leaving a pair of accidental wings called East and West Pakistan sprouting from a truncated India’s shoulders,” writes French, who concentrates on the conflict between the Congress, the government of British India and the Muslim League, which led to the transfer of power on the night of August 14-15. He also sprinkles his narrative with the personalities and character traits of leaders who changed the lives of millions: from Mahatma Gandhi, Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Sardar Patel to Lord Mountbatten and Winston Churchill.

The New India

From mapping India’s freedom movement, French moved to mapping the mind of a controversial but gifted writer, who took fiendish pleasure in playing a provocateur and had established a reputation for causing offence: Vidiadhar Surajprasad (VS) Naipaul, born in the rural poverty of colonial Trinidad, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2001. French’s candid and layered biography of Naipaul, The World is What It Is (2008), puts in perspective the talent, as well as ego, of a writer who had ‘a tendency to caricature himself in public’, outside his books: he denounced multiculturalism as ‘multi-culti,’ Islam as a ‘calamity’ and France as ‘fraudulent’.

Also read: The arid, defiant world of International Booker-longlisted Tamil writer Perumal Murugan

Part of Naipaul’s infamy lay in his branding of his ancestors’ place, India, as ‘an area of darkness’ and ‘a wounded civilisation’, where ‘a million mutinies’ raged on. French published India: A Portrait in the shadow of Naipaul’s famous India trilogy as well some other scholarly books on the rise of modern India and the challenges facing it in the 21st century, like Edward Luce’s In spite of the Gods (2004). India: A Portrait is French’s montage of a country in transition, suffused with empathy and understanding for its more-than-a-billion people, their aspirations, impulses and entrepreneurial energy. Also, a country caught in the quagmire of politics of religion, and riddled with divisions along caste lines.

“In India, I have tried to write about the country both from the inside and from the outside — or from a distance. The information passes through three different prisms. The first is political, the second economical and the third social. The individual stories, calamities, aspirations and triumphs of many people are at the heart of the narrative. Each of the three sections — Rashtra or nation, Lakshmi or wealth, Samaj or society — seeks to answer, in an indirect way, the question: why is India like it is today?” French wrote in the introduction to India: A Portrait.