How Kerala activist Rehana Fathima uses her body to battle patriarchy

Women autobiographers, from Isadora Duncan to Maya Angelou, and Rassundari Devi to Kamala Das, have questioned various forms of hegemony based on class, caste, and gender across time. Through their writing, they reimagined their identities and refused to conform to the typical expectations placed on women writers. Relying on their identity and experience, they constantly challenged the status quo, making their personal life a powerful political narrative. It’s an inward journey, often emotionally torturous, to depict one’s own life, especially when you are a woman who is outspoken for her times.

There are many examples for this dare in Malayalam, ranging from Preface to an Autobiography by Lalithambika Antharjanam and Ente Kadha by Madhavikutty (My Story/ Kamala Das) to Nalini Jameela’s Autobiography of a Sex Worker.

Antharjanam’s writing demonstrates sensitivity to women’s roles in society and the conflict that arises when she asserts herself as an autonomous individual. Though the narrative was considered revolutionary in her times, it had a built-in, unnoticed social safety net provided by her socio-cultural location. Her writings were internal engagements with her community that, in a way, subtly expressed her views on autonomy and emancipation of women.

Also read: Kerala Stories: State up in arms against Sudipto Sen’s ‘right-wing propaganda film’

When it comes to Madhavikutty, also known as Kamala Das, she had gained the threshold to cross every line drawn by the patriarchy and express her desires, despair, and disappointment as a woman made of flesh and blood. However, her cultural capital as an upper-caste woman provided her with an intangible safety net that protected her from some of the worst forms of discrimination and marginalization faced by women from lower castes.

Nalini Jameela challenged not only the patriarchy, but also the caste and class hegemony of modern society when she used her body as a weapon against social norms that view a woman’s body as something on which the honour of the family and society depends.

Reconstructing the female body

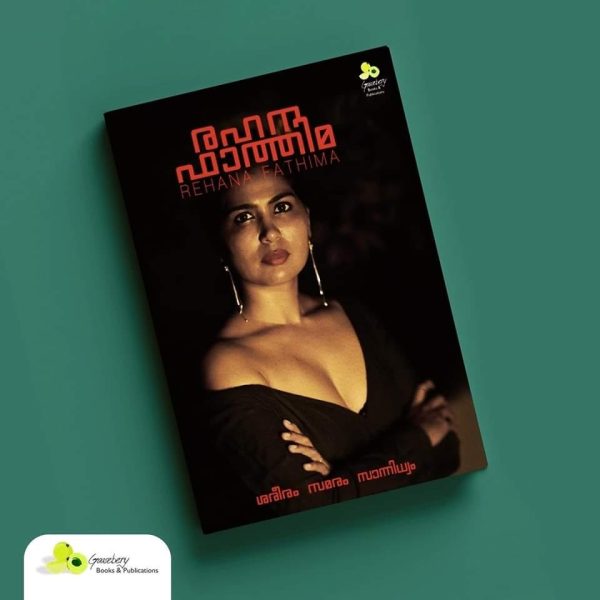

The autobiography of activist and model Rehana Fathima, Body, Struggle and Presence, belongs to the last category of writing that must vehemently confront resistance from all sides, regardless of their political standpoints.

As feminist scholar J. Devika points out in the introduction to the book, this is an “autobiography written by one of those 21st century offsprings of women, who attempt to reclaim their bodies from Kerala society’s moral grip in order to discover the meaning of life by challenging the authority that controls their bodies in its very environment and time.”

“The body, particularly the female body, is where the oppressive family system, modern state, and dominant communities manifest their power by subjugating it. Rehana’s work is an account of a young woman who realised this and attempted to reconstruct it,” observes Devika.

Fathima gained national attention in 2018, when she attempted to enter the Sabarimala shrine in Kerala, after the Supreme Court verdict that allowed all women to worship. The temple had a centuries-old tradition of barring women of reproductive age from entering, claiming that it was out of respect for the celibate deity, Lord Ayyappa. Though she had returned mid-way after the right-wing activists blocked her way, using children as shields. Fathima’s act of defiance was seen as an attempt to challenge the patriarchy and gender discrimination that underpinned this discriminatory practice.

The Sabarimala visit

A telecom technician for BSNL, and a mother of two, Fathima is known for breaking stereotypes and being a constant rebel. She was born into an orthodox Muslim family but claims to have become estranged with religion after her father’s death. Fathima had made headlines prior to her Sabarimala trip when she posed topless, covering her breasts with watermelons, to protest against a Kerala professor’s misogynistic comments. She had also participated in the Kiss of Love protest in Kochi, acted in an amateur film on intersexuality, and was among the first women to take part in the traditional Onam tiger dance known as Thrissur Pulikkali (tiger/leopard dance). All of this summed up her life before she set off to the shrine on October 18, 2018.

Also read: The Song of Scorpions review: A sublime Irrfan Khan in a stilted, inert fable

“When I decided to visit Sabarimala, I wore a bead chain with the locket of Sree Ayyappan, as per the mandatory practice. I had decided not to break any rituals or traditions. I reached a friend’s home in Thiruvalla the previous day, before the temple visit. There, under the guidance of my partner Manu, who had been visiting the shrine for years as guru swamy, I performed the traditional Kettunira ritual for the preparation and packing of irumudi kettu (travel pouch) for the Sabarimala pilgrimage. Our friends and family witnessed the whole function. He was very particular that I should not break any tradition of the ritual. It was that friend who dropped me off at Nilakkal, from where I caught a KSRTC bus to Pampa. Some people on the bus recognized me, but nobody expressed any displeasure. They were real pilgrims who had no qualms, not even an accusatory glance, with me visiting Lord Ayyappan,” Fathima explains her journey to the shrine in the book.

Rehana and Kavitha Jakkala, a journalist from Hyderabad who had also attempted to visit the shrine on the same day, were forced to climb down the hill as the pilgrims, mostly right-wing activists, blocked their way by using children under the age of ten as shields. The police, who had initially arranged protection for them, were reportedly trying to dissuade them from carrying out their mission.

“They (the right-wing crowd) were booing at us. It was a victory march for them, with intermittent Ayyappa chants and jeering. They used the children to emotionally blackmail me and did not realise their cowardice and kept on jeering,” she writes.

“None of the channels showed the visuals of children being used as human shields to prevent us from climbing the hill. I returned from there just because of this. Had I waited for long, demanding Ayyappa darshan, those kids would have suffered. Those who tortured the kids in the name of pernicious customs should have been booked under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act,” she further adds.

“After a while into our return journey, the police stopped the vehicle and started checking my irumudi kettu. A right-wing channel, Janam TV, backed by the BJP, was reporting that I was carrying sanitary pads in the irumudi kettu, and the police needed to ascertain the veracity of the news. Though the police were convinced after the inspection, the news spread like wildfire when I returned home,” she writes.

Fathima’s house, the BSNL quarter in Kochi, was vandalized by BJP-RSS workers on the same day, and she was assigned a security detail by the police. However, her rebellion did not end with the Sabarimala incident. She continued to be vocal about her feminist views and her support for the LGBTQ+ community, which put her in the crosshairs of conservative groups and politicians. They accused her of insulting Hindu religious sentiments. On the other hand, the left-leaning intelligentsia was critical of her for “falling into the hands of the right-wing.” The pro-CPI(M) cybercrowd accused her of colluding with the BJP to hatch a conspiracy against the state government.

The book provides an extensive description of Fathima’s legal fight to evade arrest and the hostility she faced from her fellow employees at BSNl, where she worked. It is interesting to note that those who criticized her include not only the right-wingers, but the so-called leftist trade unionists also, including her women colleagues. She was transferred to various offices in town, where she struggled to work in peace due to the constant acts of protest by arrogant right-wing activists.

Body as a canvas for art

Later, in November 2018, she was arrested and sent to judicial custody on charges of hurting religious feelings and promoting enmity between religious groups for posting a photo on Facebook which slightly exposed her thighs. The police action was based on a complaint filed by a Hindutva activist after her Sabarimala adventure.

In June 2020, she was again booked, allegedly for letting her children paint on her body in a video that she shared on social media. The video showed Fathima lying on the floor with her bare back and breasts exposed while her children painted on her skin. The incident sparked a controversy, with some people criticizing Fathima for what they considered to be an inappropriate and vulgar act, while others defended her right to express herself and use her body as a canvas for art.

Also read: Paachuvum Albhuthavilakkum review: Fahadh Faasil’s spark fades, Viji Venkatesh sparkles

Fathima, on her part, defended her actions as a form of self-expression and an attempt to break free from social and cultural taboos that constrain women’s bodies. She argued that her body was hers to do with as she pleased and that her children were participating in a harmless and creative activity. The controversy surrounding the incident highlighted the complex and often fraught relationship between women’s bodies which are often subject to scrutiny and control, with any deviation from accepted norms seen as a threat to social order and morality.

“To be clear, my children are not in the dark about any aspect of my private life. I don’t do anything that would embarrass them if they found out. Before my children, I never portrayed my body or my sexuality as a dubious enterprise,” she says.

“Children painting on a mother’s nude body will be considered sexual in a society that is conditioned to not distinguish between a woman’s nudity and her sexuality. It’s normal when girl children paint on their father’s body; even news stories would be published. However, in my case, it was portrayed as sexually explicit since it was a woman’s body,” says Fathima.

In the wake of the controversy surrounding her body painting and the POCSO case, Fathima has something to tell her fellow feminists. “When this case came up, a number of feminists in Kerala made me think of my own neglected sexual body. Learning that women should be modest, which is typically taught by the oldies, from feminists is not a common occurrence,” quips Fathima.

The incident involving Fathima and her children painting on her body is complex and controversial that touches on many themes, including women’s rights, artistic expression, and cultural taboos. While opinions may differ on the appropriateness of her actions, it is important to acknowledge the larger context of gender and power dynamics that underpin such debates.

Fathima’s journey as an activist and model has been marked by courage, creativity, and a relentless pursuit of justice and equality. Her autobiography is a powerful testament to the power of individual agency in the face of systemic oppression and discrimination.

In the book, which could be described as a collection of fragmented memoirs with a theme, body and struggle, Fathima narrates her early childhood miseries and her journey through the toughest times of her life. It’s not a chronological life sketch, but a political illustration of events. Even when she passively describes her breakup with her partner, whom she affectionately refers to as Manu, she had taken great care to avoid judgemental references of others.

Though your dam may be vast and strong, and you strive to hold the waves at bay, they’ll gather, fierce and wild, before too long, and drown you, come what may, warns Fathima with her life story.