How Jim Corbett typed his books, about man-eating tigers and leopards, with one finger

When Jim Corbett became an author, people often asked him how he could recall so much detail of long-gone encounters — for he claimed never to have kept a diary, never to have made notes. ‘I do not possess a note-book,’ he once wrote, ‘and I have never made a note in my life. If one uses one’s senses as it was intended they should be used, there is no need to make notes, for everything one sees or hears is photographed on one’s memory, and is there for all time… All I had to do was turn up the photograph selected and make a verbal copy of it.’ For him, this seems to have been true.

Nevertheless, the precision with which he remembered places, incidents, distances and timings remains astonishing.

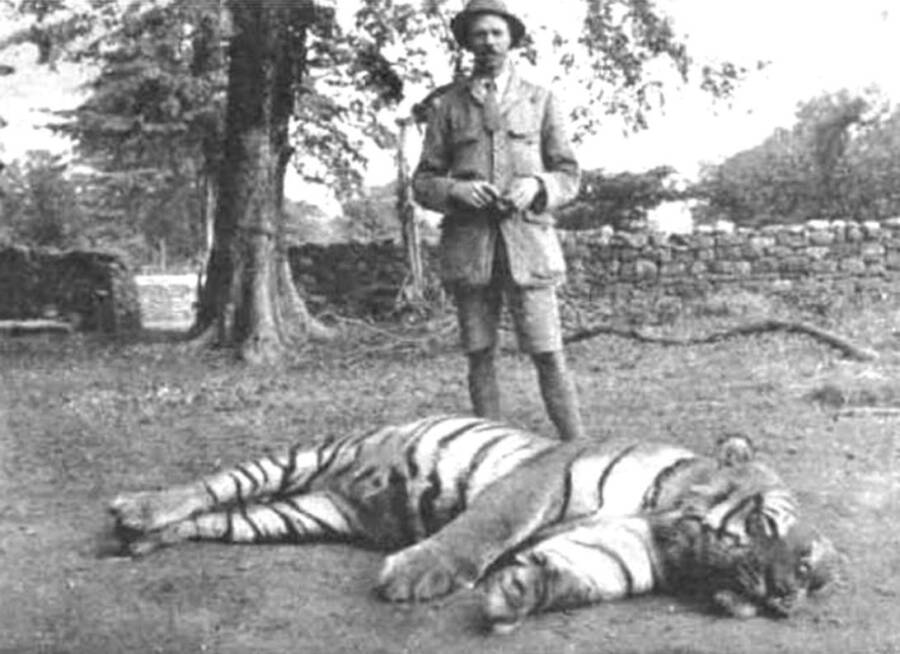

He was goaded into writing by an aggressive woman who heard him telling jungle stories one evening during a dinner at Government House in Nainital, and made him promise that he would put some of them on paper so that other people could enjoy them. Exasperated by her persistence, he agreed to make some notes. Another enthusiast was Colonel Archie White, a British officer on leave in Nainital whom he met in the 1930s. One evening they watched Jim’s film of the leopard attacking the goat, and White was so struck by the camera-man’s knowledge that he walked with him down to Kaladhungi.

Also read: The Stolen Necklace review: A gripping tale of a Muslim man’s fight for justice in Kerala

There Jim took him into the jungle and gave the call of a chital stag: within seconds a hind appeared, only to vanish when Jim gave the call of a leopard. White, immensely impressed, suggested that he should write up some of his experiences and send the results to Blackwood’s, the Scottish monthly magazine popular throughout the Empire. Jim revealed that he had already done so, but that his offerings had been rejected — and when the Colonel read them, he saw why: the narratives were so disorganised, and so badly presented in school exercise books or on tattered typing paper, as to be barely comprehensible.

‘He wanted a sentence to read smoothly’

Back in Nainital a year later, White gave Jim some coaching in grammar and syntax — and perhaps this encouraged the budding author. Perhaps Maggie (his sister, Margaret Winifred Corbett) also had a hand in shaping the stories. The creation of the text involved no small amount of work, for the author typed it — as he later typed all his books — using only one finger. As Maggie remembered, ‘He was always very neat, and if there was even one mistake on a page, he would scrap it and start another. He always wanted a sentence to read “smoothly”, and would take infinite pains in making it do so.’

The first collection was put together by a friend, editor of the local newspaper, the Lake Zephyr, who had a small printing press — but his equipment was so primitive that he could produce only one page at a time, after which the type had to be broken up so that the letters could be used again. With these handicaps, it took him four months to print the book, which the Corbetts entitled Jungle Stories. Bound in brown paper covers, but embellished with gold type on the front, and stitched with twine on the spine, it ran to 104 pages. Jim sent out seventy-five copies to friends, many of whom later reported that the book had been ‘read to death.’ The response was so enthusiastic that he started planning a larger edition; but he had not got far before Hitler (as he put it) ‘began his land-collecting tour.’

Man-Eaters of Kumaon

When he went down with typhus, he had been told he would have to spend the rest of his life in a bath chair. Refusing to accept this dismal prediction, he exercised vigorously and got down to revising the manuscript of his book. When he sought advice from a friend who had brought out a book of his own, he was told that no publishing house would accept his typescript unless he indemnified the firm against all possible loss.

Also read: Feeling Kerala review: An anthology journeys into the heart and soul of God’s Own Country

Having talked the matter over, he and Maggie decided that there could be no harm in asking a publisher’s opinion; so, early in 1943, they sent a new version of the manuscript — again entitled Jungle Stories — to the Bombay branch of the Oxford University Press, bolstered by recommendations from Linlithgow, the Viceroy, and Sir Malcolm Hailey.

Hailey remembered that Jim had no idea of the value of his work. ‘He did not realise how enthralling were the stories he had to tell, nor how greatly their interest would be enhanced by his manner of telling them. Yet… he possessed that supreme art of narrative which owes nothing to conscious artistry.’ Roy Hawkins, known as ‘Hawk’, the editor in Bombay who came to handle most of Jim’s writing, was certain from the first that the book would be a huge success — especially when an American war correspondent, to whom he sent proofs for an opinion, returned them saying he had been so entranced that he had read the stories three times. So the O.U.P. accepted the book for publication, insisting only that its title be changed from Jungle Stories (which meant practically nothing) to Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Jim dedicated the book to ‘the gallant soldiers, sailors and airmen of the United Nations who during this war have lost their sight in the service of their country’, and specified that all royalties from the first Indian edition should go to St. Dunstan’s, the training school for Indian soldiers blinded in the war, which had opened in 1943.

The first edition was published by the O.U.P. in Bombay in August 1944, and immediately attracted the attention of the new Viceroy, General Sir Archibald Wavell:

The Viceroy’s House,

New Delhi

My Dear Corbett,

I have just finished reading your book, and have hardly ever enjoyed one more. They are thrilling stories, and you have told them extraordinarily well. I have already ordered several copies for friends.

Another edition appeared from the branch of the same publisher in Madras in 1945. In the West, the book came out simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic in March 1946, with an introduction by Hailey and a preface by Linlithgow. As in India, it took off like a rocket. ‘It would be fair a fair guess that Man-Eaters of Kumaon is the most beguiling book about big game hunting ever written,’ said James Hilton in the New York Herald Tribune.

Jim had been invited to a large publication party at the O.U.P.’s headquarters on Fifth Avenue, but he had felt obliged to decline. According to the firm’s publicity chief, Virginia B. Carrick, ‘Colonel Corbett was greatly missed. He sent me a wonderful cable which I had photostatted and blown up so that it could be hung on the wall and read by the guests at the party.’ Henry Z. Walck, President of the firm in New York, took a hand in the publicity campaign, and organised the printing of posters which depicted tigers with eyes that glowed with luminous ink.

Also read: Book excerpt: When Droupadi Murmu delivered her maiden speech

Luckily a suggestion that tiger skins should be exhibited in shop windows was never taken up. Reviews were enthusiastic, the sole dissenter being the spiky author and critic Edmund Wilson, who described Jim’s style as being ‘like ruptured Kipling’ (he later called J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings ‘juvenile trash’).

The American Book of the Month Club printed 250,000 copies, and two tiger cubs, flown to New York in a private plane from a zoo in Florida, autographed copies with their pug-marks at a reception in the Hotel Pierre. Complaints about the number of ‘gruesome tales’ the book contained left the author unmoved: ‘I can’t help this, for if I did not paint the whole picture as I saw it, there would be no point in trying to paint it at all.’

(Courtesy HarperCollins India)

(Duff Hart-Davis is a distinguished biographer, naturalist and journalist. He is the author of 17 non-fiction books on subjects ranging from Hitler’s Olympics, the adventurer, Peter Fleming, to a history of the mid-Atlantic island of Ascension. He has also published eight novels. Duff was brought up on a farm in Oxfordshire. He did his National Service in Germany and read Classics at Oxford. He is married with two children and now lives on a farm in the Cotswolds.)