Encounter with vodka à la Rooskie: When two Russians went berserk

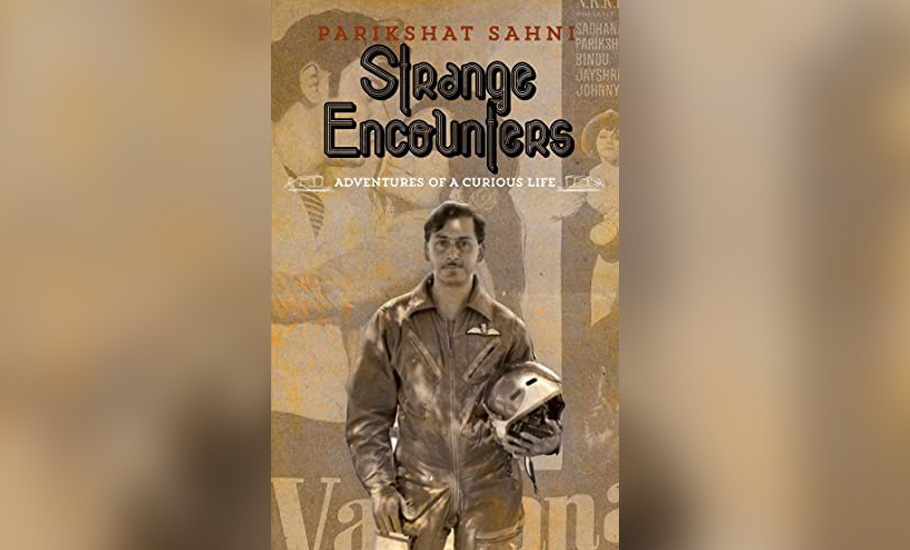

An excerpt from ’Strange Encounters: Adventures of a Curious Life’ by Parikshat Sahni, in which the actor recollects the violent altercation between two hefty Russians, Jena and Petya, at the hostel of the film institute in Moscow in the spring of 1961

They say “whisky makes you frisky” and “brandy makes you randy”; gin, as far as I have learnt, has the opposite effect on a man’s libido, and, judging from the fact that the Indian jawans are regularly fed on it, rum probably makes you fearless. But what about vodka?

Well, it is the staple drink of the Russians and as far as I know from personal experience, it makes a man go berserk. I—never having learned moderation in anything—imbibed vodka copiously during my years in Russia. The Rooskies drank it at the drop of a hat. They drink because of the cold, and when they’re feeling frustrated, and when they’re happy; they guzzle it when they are sad. The Russians drank vodka “alike in pain and pleasure, profit or loss, victory or defeat,” to paraphrase a sentence from the Bhagavad Gita. For them any occasion was the right occasion for vodka. It gave them a terrific kick and sorted out most of their mental, spiritual and emotional problems. I followed their example enthusiastically.

The Bloody Marys and Screwdrivers are aberrations of the decadent West; after a few glassfuls of vodka à la Rooskie, a man sees red and is prepared for anything — the best or the worst. What the Germans feared most during the Second World War was the “madness” of their Russian counterparts. One German officer wrote, “I have never seen such tough dogs as the Russians.” Another one found “something diabolical” about them. Not only the men but also “the female soldiers were generally considered more determined and less willing to surrender, notably more aggressive in close combat, but also as especially heartless, cruel and unlikely to take prisoners.”

Also read: How Kalachuvadu Kannan changed the face of Tamil book publishing

Although the Russian soldiers were often short on rations, they were never short on vodka. After a couple of glassfuls, the German soldiers did not know what hit them. It was not uncommon for Russian soldiers, both men and women, to carry heavy explosives and throw themselves under oncoming Nazi tanks and blow themselves and the tanks to smithereens.

Stalingrad was the worst nightmare for the Nazis. The battle of Stalingrad was called the “battle of the rats” and the two sides had to fight building to building and room to room. In the end, the Nazis surrendered but they never got rid of their dread of the “diabolical” Russian. Well, the “madness” that they so feared, I think came from the power of the secret Russian weapon — vodka!

To cut a long story short, imbibing this brew à la Rooskie is like sending an invitation to the devil himself.

I got first-hand demonstration of this within a few weeks of moving into the hostel of the film institute in Moscow in the spring of 1961. I was sharing a room with two hefty Russians, Gena and Petya, both in their early twenties. I knew no Russian and was having a very difficult time finding my way around Moscow. The rooms in our five-storied hostel were small and each floor had a common kitchen and a common toilet.

Dad had equipped me well for my stay in Russia. I had brought along an impressive wardrobe. Mr A.K. Hangal, who was a tailor in those days and had a small shop in Crawford Market, had made some snazzy suits for me. He was a Marxist and he beamed as he took my measurements and said, “You are lucky! You are going to the greatest country in the world!”

As luck would have it, it was his suits that caused me to get my first black-eye in Russia. My roommates didn’t like the look of those suits. Gena, the larger of the two Russians, thrust his finger at my chest after surveying my wardrobe and said menacingly, “Kapitalist!” I tried in my broken Russian to explain to them that my father was, in fact, a Marxist and not a capitalist, and that I believed in socialism myself. But the fellow cut me short and yelled, “KAPITALIST!”

I offered to share my clothes with them (the clothes most Russians wore in those days were drab and ill-fitting) and before long they were wearing not only my shirts and ties but my underwear too.

Most young Russians in those days were frustrated and dissatisfied. It was partly due to the high cost of living, lack of quality goods, and lack of freedom of speech. The Soviet state ruled with an iron hand. It was ruthless, merciless and oppressive. It brooked no criticism or dissent. Life was difficult. The only thing that was cheap and of high quality was vodka, and the Russians drank it to excess to alleviate their frustration; even that could not relieve them of their inner discontent, which often boiled over. And when that happened all hell broke loose.

One day, Gena went out to a party. It was well past midnight when he got back. Petya and I were fast asleep when he pushed the door open loudly and walked in singing some Russian war song at the top of his lungs. The fellow was pissed out of his mind. This infuriated Petya and he got up with a roar and went for Gena, all hammer and tongs. I think they had an old axe to grind and needed just a pretext to have a go at each other.

What followed next was a fistfight the likes of which I had never seen before. Both were strong men, and Petya had the physique of Hercules. Also to be noted: Petya was stark naked—night suits were rare in those days; most Russians slept in the raw. Cursing, biting, scratching, they threw one another against the walls and the entire floor shook.

Also read: Bangladeshi artist Rokeya Sultana: I learnt humility, tolerance in Santiniketan

Gena felt that the best way to pound Petya into submission was to squash his balls, and grabbed them with the intention of tearing them off and emasculating the other fellow forever. Petya roared like a wounded lion as Gena squeezed his testicles with all his might. I was watching the proceedings from under the blanket and was sure that the decimation of the testicles would put an end to the fight, but I had underestimated the Russian spirit.

Petya, instead of surrendering, picked up a dumbbell and began to pound Gena’s head with it. I was sure that the latter’s skull would crack; but I had also underestimated the thickness of the Russian skull. Bruised and bleeding, Gena did not weaken his grip on Petya’s balls, and both bellowed like bulls on heat.

Fearing castration, Petya finally offered truce. Gena’s face was a mask of blood. Seeing that his opponent was vanquished, Gena let go of Petya’s balls and stood up, panting hard, sure that he had taught his enemy a lesson. But Petya was not easily vanquished. He suddenly picked up a frying pan and smashed it hard on Gena’s head. That ruined the frying pan (it bent double) and Gena roared in pain. I thought the battle was over but Gena was in a rage. While Petya was nursing his bruised balls, Gena’s drunken eyes noticed me cowering under the blanket. I cringed. “KAPITALIST!” he shouted and, pulling me out of bed, threw me against the cupboard. My pleas for peace and “Panchsheel” went unheeded.

(Courtesy of Simon & Schuster India)

Parikshat Sahni is an Indian actor who is best known for playing the lead roles in Gul Gulshan Gulfaam (Doordarshan), Gaatha (Star Plus), and Barrister Vinod. He has also appeared in Rajkumar Hirani’s films Lage Raho Munna Bhai, 3 Idiots, and PK. He is the son of noted actor Balraj Sahni and nephew of Bhisham Sahni, a celebrated writer.