Book Excerpt: How Hindi poet Manglesh Dabral explored the idea of ‘the other’

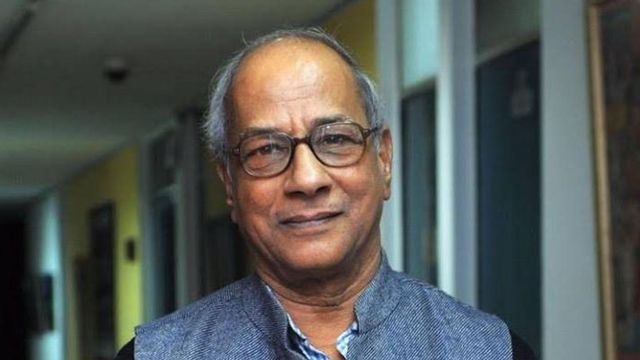

Among the post-Raghuvir Sahay generation of poets, Manglesh Dabral (1948-2020) stands tall as a poet who has consistently been exploring the idea of ‘the other’ in the Indian socio-political discourse as a tool to understand as well as reflect the change in his surroundings. It is perhaps the most integral aspect of his poetic journey in which the cross currents of different worlds find a disturbing echo.

In fact, for Dabral, coming to terms with the reality of the other is almost akin to coming to terms with himself; his inner world and his poetic journey seems to be unconsciously working towards a kind of reconciliation between the two. It is certainly not an easy journey to take, and what separates Dabral from many of his contemporaries is his ability to absorb the ever-changing distressing realities that lie beyond the boundaries of his everyday ambience.

The dark realities of life

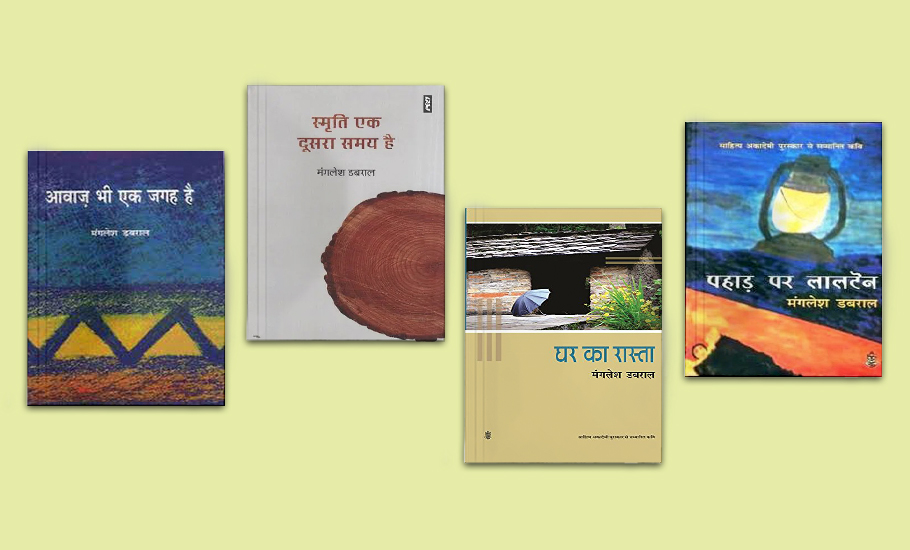

In his first collection of poems, Pahar Par Lalten (A Lantern on the Mountains, 1981), he has some vague notions of the other in the form of ‘his shadow’ that automatically becomes ‘another person’s shadow’ in the Section 4 of Train Me Saat Kavitayen (Seven Poems in Train, 1977). This vague notion is further concretized when he gets aware of his ‘other hand’ that is ‘almost in disuse,’ oblivious of the bad world that the main hand encounters day in and day out.

Also read: How Pinocchio, the long-nosed puppet boy, has journeyed across time

It is only when things are stretched a bit far that ‘the other hand sometimes registers its protest’. However, this awareness of the other still carries a tone of patronage as the poet believes it ‘remains hidden somewhere like a hare in the bush’ or ‘between ball and the wooden horse of his childhood’, perhaps not ready or not meant to engage with the dark realities of life.

This awareness of the silent identity of Doosra Haath (The Other Hand), written in 1983 and collected in Ghar Ka Raasta (Path to Home, 1988), takes a great leap and in Sangatkaar (The Accompanist, 1995), included in Awaaz Bhi Ek Jagah Hai (Voice is also a Space, 2000), it gets transformed into a symbol of something of a historical relationship between the dominant and the minor with the experiences of the minor in the focus: Since long ago/ The resonance of his voice has echoed/The sonority of his master’s.

The silhouetted identity of the other

But the restlessness of Dabral’s poetic journey does not allow him to be complacent. The recognition of the silhouetted identity of the other inevitably leads him to a painful understanding of the reasons behind his own backwardness as an individual as well as a social being as he finds he has ‘two lives’ to handle in a manner in which the success of the one is not dependent on the failure of the other: Had I only one life I would have reached immediately/ Would have arrived somewhere successfully/—–/But I have two lives to contend with at the same time.

In his perhaps the most mature poem of the later phase, ‘Two Lives’ (Kathadesh, May 2008), we find that the other walks with him on equal footing — My one hand often pushes some mountain/ With my other hand I hold on to a piece of sky — even though the agonizing dramatization of the poet’s situation in these lines makes it a reflection of the forked times that we are living in.

Also read: ‘Qala’ review: A sensual mood piece, a strange little psychological puzzle

The secular poetry of protest

What may appear to be Dabral’s temporal and apparently simplistic movement towards the proper understanding of the other is actually a reflection of the revolutionary socio-political changes that have been sweeping the Indian landscape for the last two decades, especially in North India.

A significant poet like Dabral, trained under the parameters of the left-liberal poetic dialogue, responds by criticizing the mindless globalization taking place in the society where one day, when humanity loses all its humanness, it will be ‘rewarded’ with ‘the key to a big car and a fat cheque’ (Bhoomandlikaran, Globalization, Kathadesh, May, 2008). He goes further and directly attacks the divisionary tactics of the reactionary forces and leads the secular poetry of protest of our times.

But the problem for Dabral’s generation of poets comes when it has to deal with the historical analysis that is brought in by the post-colonial writers in the form of Dalit writings and writings by women. This makes it all too complex, a complexity that was denied to a Muktibodh (1917-1964) or a Raghuvir Sahay (1929-1990) — the pioneers of ‘modern’ Hindi poetry. It certainly arises out of the clash of ‘alternatives’ brought about by the economic liberalisation of, by and for the upper-middle class, on the one hand, and the rise of the subaltern consciousness forcefully altering the agenda of the socio-political discourse as well as power structure, on the other.

The communal agenda is brought in to create confusion about the terms of these discourses and changes.

In the face of this onslaught, when the majority of the poets of Dabral’s generation appear to take the shortcuts of uncritical admiration, patronage, or turn inward and start regretting the loss of the so-called tranquil past, Dabral pulls himself up and makes genuine engagement with the sociology and the psychology of, what many believe, the ‘real’ poetry of protest.

Not only in ‘Two Lives’, but also in a masterly crafted poem ‘Chhhuo’ (Touch, Naya Gyanoday, 2007), we find him drawing on the values and systems that have been considered ‘untouchable’: Do not believe in instructions like ‘Please Do Not Touch’ or ‘Touching Not Allowed’/It is a conspiracy in vogue since time immemorial’.

Also read: Tamil writer Imayam on female desire and why writing is a political activity

The muted, almost sensuous tone of the poem also gets linked up with a range of poems about personal relationships that Dabral has written in abundance but has remained under the shadow of poems that have pronounced social relevance. It is a reflection of Dabral’s poetic range that his personal memory, regret, sense of loss and failure allow him to identify with wider human suffering. Such poems abound in his collection Hum Jo Dekhte Hain (That Which We See), in particular, where he engages himself with his childhood, the mountains where he grew up, and the pictures of his ancestors that he tries to relate with.

Similarly, in his collection Awaaz Bhi Ek Jagah Hai (Voice is Also a Space), which was noticed for its range of poems on music and musicians, we find that he is capable of relating with the other in some unknown, unseen moments of spontaneous love: while walking, someone else is found walking along side/and in darkness, too, an arm appears with love (Drishya/Scenes).

(Courtesy of Nirala Publications)