Bombay is the cultural and psychic cradle of my characters: Rahman Abbas

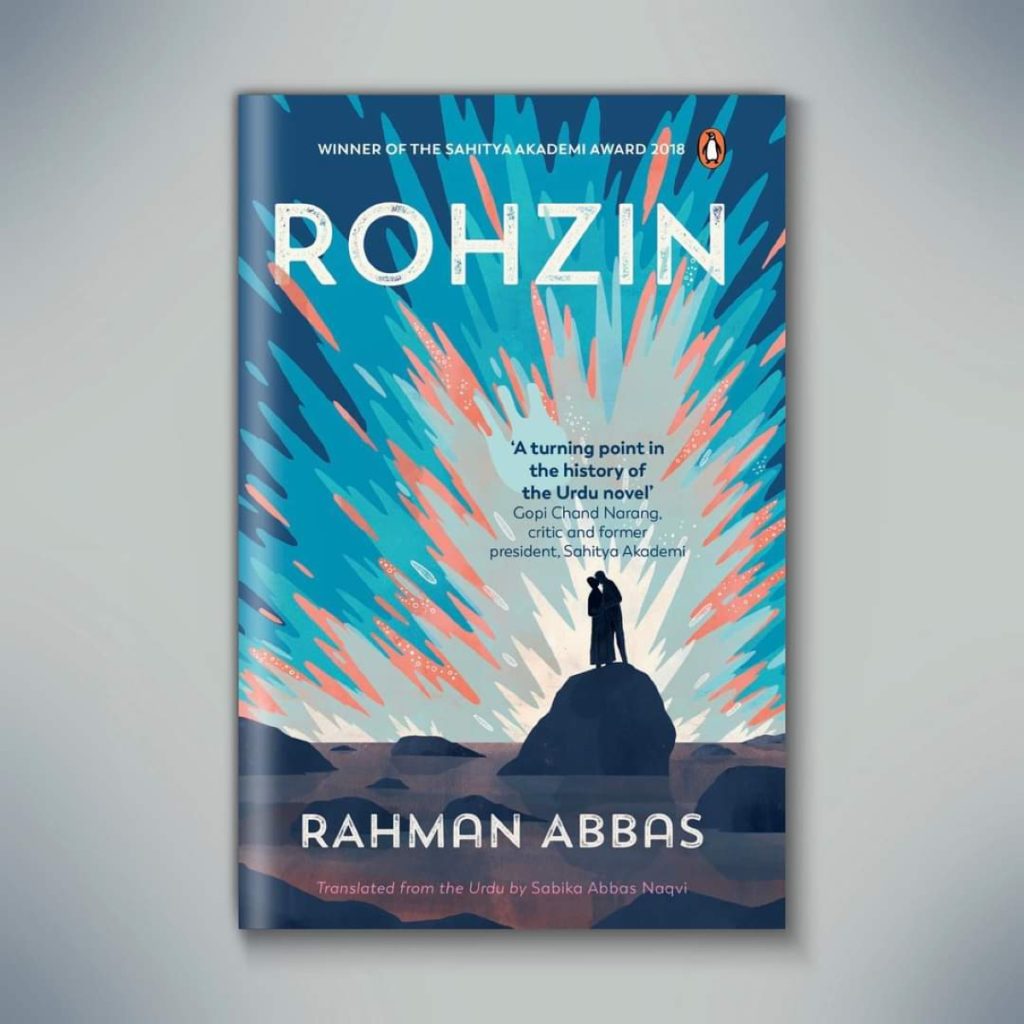

Rohzin (Penguin Random House), translated into English by Sabika Abbas Naqvi, is the fourth novel by the Mumbai-based Urdu novelist Rahman Abbas. On Saturday, it made to the longlist of the 2022 JCB Prize. His latest, Zindeeq, unfolds on a wider canvas.

In an extensive email interview to The Federal, Abbas talks about going beyond the conventions of Urdu novels to write about the sexual experience, how the city he lives in shapes the landscape of his fiction, and why few Urdu writers have the courage to experiment, liberating themselves from the burden of ideologies, be it progressive or modernism. Edited excerpts:

Rohzin, like your previous novels, stands out for its bold themes and stylistic experimentation. Right from coining the title to capturing the trauma of children who witness the betrayal of their parents sleeping with someone else, to that of the village, MabadMorpho, you portray a world in which legend and folklore, mythology and history, realism and surrealism, memories, dreams, and reflections collide and coalesce. How did you arrive at the story?

I had first-hand experience of the Bombay deluge on July 26, 2005. There were many sad stories about how people had died, including many couples who had gone to the seashore, on that fatal day. I tried to imagine what could have happened to them if they had been caught by the rage of the sea at the time of the cloudburst.

On the other hand, I had this theme of the children who witness the betrayal of either of their parents. How could this affect the lives of those who witness it? In Urdu vocabulary, there is no word to describe the trauma of these children. I coined the word ‘rohzin’ (melancholy of the soul) by combining ‘rooh’ (soul) and ‘huzn’ (melancholy).

In Urdu, ‘mabad’ means ‘post.’ I derived ‘morpho’ from Kafka’s Metamorphosis to change the form. At that time, I was thinking about a new form to tell the tale in the post-Metamorphosis age. So, I blended a lot and tried to experiment with the narrative, employing the elements of legends, folklore, mythology, and history, among others.

With all this in head, I tried to imagine what would have happened to the couple that visited the seashore on that unfortunate day. Thus, all the elements were used as scaffolds to bring forth the love story of Hina and Asrar, the protagonists of the novel. Simultaneously, they were merged into the context of the story to create layers into the text.

Professor Gopi Chand Narang, one of the greatest Urdu scholars who passed away recently, had termed Rohzin as a turning point in the history of the Urdu novel, which has been used as a blurb on the cover. How do you see the novel departing from the tradition of fiction writing in Urdu?

I’m simply honoured by this comment of a critic and scholar of the stature of Gopi Chand Narang. He must have had something in his mind. The literary tradition of Urdu novels has been shy when it comes to the description of feelings of love, lovemaking or sensuality. The Urdu novel, under the pressure of puritans, has always avoided to express what we feel when we touch, indulge or have sex with a person we love or even those we don’t. The Urdu novel has never celebrated sexuality. In our stories or novels, exploitation has been portrayed extensively. Hence, there are stories of prostitutes or harems of Nawabs. Rohzin, on the other hand, questions and explicitly demonstrates many forms of sexuality. It also separates love from sex; it depicts both without judging the one involved in eather. While I don’t advocate unnecessary sensuality in the text, to avoid it when it is necessary is akin to doing injustice to the emotions of the characters.

Your first novel, Nakhlistan Ki Talash (The Search For An Oasis, 2004), set in the backdrop of the demolition of Babri Masjid, chronicled the radicalization of a young man from Bombay in the aftermath of the 1992 riots. What was the genesis of the novel? How did you arrive at the voice of the young narrator?

The genesis of the novel was the orchestra of riot itself. The suffering of the city was the suffering of all of us. We had seen how emotions were exploited in the name of Hindutva for certain political objectives: to rule and to subjugate those having different faith or identity. We had also witnessed how the Islamists exploited the suffering of people in the name of faith and identity. The organised riots had played a role in radicalization. Since I had seen both sides closely, I wanted to chronicle that as honestly as I could. However, now when I read that novel, at places, I find it louder, and betraying the aesthetics of fiction.

Also read: Five myths about Shakespeare’s contribution to the English language

How do you look back at the needless and prolonged ‘obscenity’ trial that you had to face after its publication and the personal costs those years entailed?

It was suffering — mentally, socially and financially. Then, I was a lecturer at Anjuman-e-Islam, which had its main branch at Victoria Terminus, which is now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. I was removed from my job under pressure from politicians and Islamists. It was difficult for me to get a job at minority institutions as Urdu newspapers had maligned me through a campaign. I had to spend two days in Arthur Road Jail. Then, I had to manage to pay fees to the lawyers. After a decade, the trial ended, but for all those years, I had to go to the court and stand in front of the judge, like Josef K. in Franz Kafka’s The Trial, not knowing what his crime was. However, in those days I learnt my lesson that writing, sensitive writing, had a price. And, as an author, one had to be ready to pay it. I learnt to reconcile with the fact that what happened to me had happened with writers before. I understood that not everyone will react to my writing in the same manner; sometimes, people react differently. One had to have faith in oneself; so, I continued writing as there is no better antidote to dogmas and orthodoxy than writing.

Even though it’s a political novel, it’s also a tender love story, and a Bombay (now Mumbai) novel, at its heart — just like Rohzin. Do you see yourself particularly drawn to the overarching themes across your novels: love, longing, and sexuality? How central is the city of Bombay to your creative osmosis that finds manifestation in most of your novels?

The main function of the novel is to explore the human existence and various aspects of relationship. Everything else — including society, ideas, politics, religion, economy, ethos, milieu or narrative techniques — is complementary and supportive. Bombay is the setting that gives a different colour to my characters. People living in different cities experience life differently: their sensual encounters with culture, passion, love, and death vary. So, the kind of stories I tell cannot be felt real if their background is not Bombay. This city is also my love. I have seen its many forms, faces, colours, and magic, and I try to bring that in my work on the ground that Bombay is the cultural and psychic cradle of my characters. These characters are nurtured by this city, and both its past and present. For me, this city itself is a character, a mirage or illusion. The lives of the characters of this city have love, longing and sexuality in their destiny. I just try to grasp it.

In Rohzin, along with love and desire, did you set out to explore the complexities of identity, both religious and linguistic? The novel has several strands that dwell on the city’s underbelly: the beggars and drug addicts, the homeless, and the victims of sexual abuse. How did you go about researching the dark underbelly of the city, and its inhabitants?

The city is my experience. I have lived with all such people. In my school days, I lived in the company of beggars, drug addicts, homeless, and abused. The identities are something that came out without me having to think much about them.

Also read: They finally got through to an unsuspecting Rushdie

The chapters of most of your novels are titled after the first line of a couplet. Your prose, too, seems to have a cadence of its own. How do you work on the terrain of your prose?

I love poetry and read a lot. So, I have used couplets from some of my favourite poets in naming the chapters of Rohzin. This is my way to remember them and to pay my respect to their creativity. Urdu is not my mother tongue; I’m a Konkani-Marathi Muslim. Konkani dialect is my mother tongue. It is evident from my prose; it doesn’t carry the flavour of North Indian authors. I have had my challenges and difficulties. I have made mistakes, errors and even blunders, but I believe in learning. I feel I’m still learning how to skilfully use the language. However, I have my ways of description: I give more weightage to the sound of a word while dealing with it and I try to build a sentence with much care, imbuing the text with layers.

Your latest and fifth novel, Zindeeq, unfolds on a wider canvas. A dystopian novel, it draws a parallel with Nazim’s effect in Europe with the likely impact of religious extremism on the Indian subcontinent. How was the process of working on this novel? How did you weave in a wide range of themes into its fabric? Could you talk about the new narrative style, mythological realism, you devise in the novel?

A creative mind cannot live in isolation or escape from the realities around him. Zindeeq is an outcome of my fears and nightmares. Luckily, I got the research grant to visit Europe, especially Germany, to witness the Nazi past: I had received the ‘Crossing Borders’ research grant funded by Robert Bosch Foundation and Literarisches Colloquium Berlin. The Nazi past in this book is, in fact, a mirror that can show us what will be our future if we fail as a democracy: The future of the entire subcontinent. The religio-political and racist-supremacist narrative is gaining momentum in both the countries. What are its objectives, what is its destination? The novel is just an effort to trace the journey of this narrative.

In Rohzin, I had used mythology as it was used by many Urdu writers, like Rajinder Singh Bedi or Intizar Hussain. But I was looking for something else; in the new era, in the age which has seen a lot of magical realism or surrealism, how else could one experiment with the narrative? So, one day, I thought, it could be “Mythological Realism”, it has the capacity to blend all —magic realism, surrealism, social realism, history, past and future. Thus, as far as form and style is concerned, Zindeeq is my experiment with the Mythological Realism, I don’t know if I have succeeded in or not. But a lot of people in India and Pakistan, who have read the novel, have shared that despite its thickness (780 pages), it is an engaging read. Its third edition has recently come out in India, and the second edition in Pakistan. Perhaps my experiment with Mythological Realism to tell the awful story of our bleak and dark future has clicked with them.

In the epigraphs of your novels, you have quotes from writers across a wide spectrum: James Joyce, Milan Kundera, John Fowles, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mark Twain, Ben Okri, and many others. Do you see them as having influenced your own approach to novels and the understanding of its possibilities?

I have enjoyed reading these and many other writers, and I have learnt a lot from Marquez. He has helped me unlearn many things, especially that which was propagated by ‘Urdu Modernism’ or Shamsur Rahman Faruqi about the leitmotif of fiction in Urdu.

How do you look at the state of the Urdu novel today? Can you name some promising Urdu writers who should be read?

The state of the Urdu novel in India is sadly pathetic. I don’t find many authors having the courage to experiment, explore or say something afresh aesthetically, or liberate themselves from the burden of ideologies, be it progressive or modernism. It is sad that talented writers are still following tools propagated by the modernist critics in Urdu. A writer, in my view, should invent his own tools; the one who subjugates himself to the vision of a critic about the Art of Fiction is a slave and must be condemned. Some novelists in Urdu are writing about the state of Muslims in India (almost all of them are biased); some are writing about corruption (but there is no novelty in it); some are writing about the loss of cultural heritage (they are rightist and cannot face the truth of present); some are escapists or the remnants of the Urdu Modernism. In addition, there are some who fit in the category of ‘copyist’ who have started to write novels in their sixties or post-retirement when they realised that they are neither a good poet nor a good critic or lured by the fact that novelists are getting more attention recently. If I recall it accurately, Nissim Ezekiel had said that while some write novels, some are the novelists. So, for me, such people are not novelists, though they have written stuff similar to novels. Having said that, let me add that Syed Muhammad Ashraf, Abdus Samad, Shamoil Ahmed, Sarwat Khan, Siddiq Alam, Zakia Mashhadi, Shaista Fakhri, Khalid Jawed, Noorul Hasnain, Sadiqua Nawab Saher, Anis Ashfaq, Ghazanfar, Yaqoob Yawar and others are in the field and they have their readers. Now, as far as promising novelists are concerned, Mohsin Khan and Shabbir Ahmed have come up with their first novels recently, both have got good coverage and reviews. Their subjects are different as much as their treatment.