Vinay Shukla’s documentary While We Watched envisions a political dystopia of television newsrooms and broadcast journalism in India. The film presents an intimate glimpse into the professional and personal life of former New Delhi Television (NDTV) news anchor and senior channel executive, Ravish Kumar.

Drawing primarily on behind-the-scenes footage of primetime news with Ravish Kumar on NDTV, the documentary is a portrait of the collapsing political economy of media culture in the world’s largest democracy, where the integral principles of broadcast journalism are under attack by right-wing television anchors, and their rampant fear-mongering and trend-setting of branding of any form of dissent as unpatriotic and ‘anti-national’.

A glance into Ravish Kumar’s world

In his film, Shukla foregrounds the bid by competing news channels to increase their target rating point (TRP) by unscrupulously capitalising on the neurocognitive anxieties of general television viewers. The film is strategically edited with archival reportage of chaotic live-debates on Republic TV, unverified fake news, pixelated mobile phones videos of mobs, misinformation spread by highly dramatized op-eds and anchor bytes and the never-ending catastrophes of breaking news, all of which reflect the dark side of broadcast television.

On a timeline, the documentary begins with the 2019 general elections and the landslide victory of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Over the course of two years, which includes the onset of a global pandemic, Ravish Kumar’s primetime show on NDTV increasingly appears as the last outpost of rational political thought and idealist optimism on broadcast television. Kumar can be seen on the sets of a newsroom, politely yet firmly rebuking viewers, by asking them to turn off their television sets instead of passively watching the live telecast of inflammatory hate speeches, while trying to dissuade the spreading of fake news shared via WhatsApp groups and other social media platforms.

Also read: Barbie review: Greta Gerwig’s bittersweet ride through nostalgia, feminism, and frivolity

The documentary offers a glance into Ravish Kumar’s world, his relationship with co-workers and the production unit, and stands as a testimony to the strength of his character. One bears witness to how his intrinsic resistance to monolithic concentrations of power manifests into a set of habits and actions that constitute his daily life.

In other words, there is a redolent harmony between Kumar’s expression of political intent (dharma) and his everyday actions (karma) which is a mark of the highest distinction, and fully deserving of recognition, as with the Magsaysay Award in 2019 and the take-off of his personal YouTube channel, with over 6.51 millions subscribers. The YouTube channel, Ravish Kumar Official, streams daily news content and is the consequence of his recent resignation as executive editor at NDTV, following its acquisition by the Adani Group.

On courage

In the world’s largest democracy, the advance of digital technology has led to an ongoing dehumanisation of citizens, journalist and writers, which is increasingly the subject of investigation among media scholars. In the digital era, there is a cognitive embodiment of mass-hysteria, whether it is via fake news that leads to the improvised concerting of mobs, or the swarming infractions of trolling and the organised targeting of individuals on various social media platforms by IT cells. Conflated against this backdrop, Ravish Kumar’s rational and polite response to the invocation of fear and paranoia in the infosphere divulges the possession of a courage that is almost superhuman.

Much like Shukla’s previous documentary, An Insignificant Man (2016), co-directed with Khushboo Ranka, follows the meteoric political ascent of Arvind Kejriwal, and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) — the biopic on Ravish Kumar, While We Watched, focuses on another seemingly common man’s will to courage, particularly his steadfast rationalism when confronted with the political upheavals of the majoritarian masses.

One observes that Kumar is not intrinsically prone to fits of fury and tantrums on-screen, he balks at mainstream broadcast television that repeatedly short-fuse into crisis, disaster and outrage and, therefore, gets branded as an ‘anti-national’ by his media rivals.

Kumar’s mobile phone turns into a 24-hour hotline for disillusioned religious fundamentalists, and their incoherent tirade of expletives, death threats, and hate speech, leaving him suspended in a perpetual state of neurocognitive anxiety, fearing for the safety of his family, while tackling mobs that suddenly turn on him even as he is reporting live from the streets of New Delhi.

The refusal to be dehumanised

Contrary to the conditioned human response to shut down in an environment of intense stress, Kumar speaks up even more coherently, politely, and reasonably and there is an active refusal to be dehumanised by the terrifying turn of mob violence and personal threat to his family.

An extraordinary courage lies in the refusal to respond obsequiously to power, wherein a radical form of polite reasoning is underway to take on the political work of dismantling hegemonic power. There is commitment to non-hierarchical forms of world-building that permeates every aspect of Kumar’s life, including his relationship with his co-workers and his role as a husband and father to his young daughter.

For instance, on a stressful day at the newsroom, Kumar is repeatedly misreading his lines in front of the camera because of the faltering teleprompter. Finally, he gets angry and tells the operator to do his job properly.

Meanwhile, the operator, who is equally frustrated, pointedly asks Kumar to not tell people how to do their jobs and to stop accusing him without clearly understanding what the problem might be. Instead of taking this as an affront by a member of his production, Kumar politely starts explaining that he is justifiably angry because he spent many hours in the morning working on his script for the show, which he cannot read from now because of the faulty machines.

Also read: Oppenheimer review: Breathtaking visuals, enigmatic Murphy make for a flawed yet thrilling fare

There is a keen attunement to the psychic life of power that allows Kumar to incisively diagnose the tendencies among those around him to be slavish to power; and it is beyond exhilarating to watch Kumar dismantle the internalised structures of fear and self-censorship from one of the best scene in the film, where he is moderating a debate at the Delhi University campus. The professor inaugurating this event ventures a few sentences on national pride; it is a weak attempt to circumvent the possibility of having extended an invitation to a public figure, who has been branded an ‘anti-national’.

Sensitising viewers to journalistic integrity

Kumar recognises this and does not fail to call her out for appeasing to an existing climate of fear and censorship in the universities. He points out that no one has the right to terrorise others because they do not conform to standards of jingoistic patriotism that is underway in the media today, or because they belong to an ethnic minority group and there is a huge applause from the students and faculty. Such moments of rupture in the film produces an emotionally charged experience for viewers.

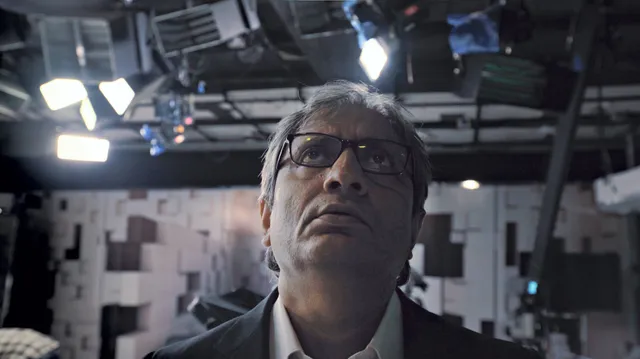

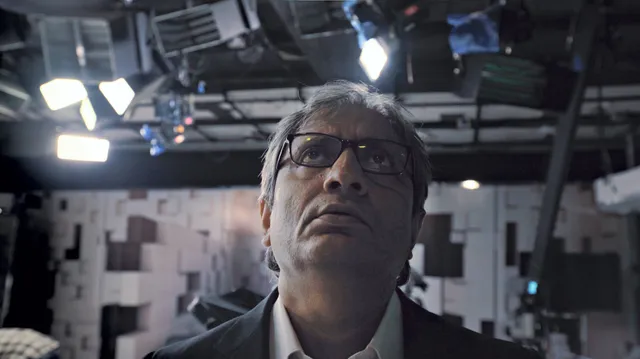

Shukla has insightfully pointed out that Ravish Kumar is a well-known journalist in the country and people are used to seeing him on prime time television every day. However, most images of him are frontal, where Kumar either is seated behind the news desk or facing the camera and his audience while live-transmitting from different locations of the capital.

Therefore, Shukla remained focused on close-up or oblique shots to capture Ravish Kumar in an intimate setting as he went about his quotidian activities, both at work and with his family. Shukla also explains that his objective with the documentary was to reroute the apocalyptic tone and techniques used for editing breaking news, but to the countereffect of sensitising viewers to the damage to journalistic integrity and the misuse and misinformation of broadcast television.

Whether as an antidote or a necessary deflection, the film happens to be replete with shots of cake-cutting at any given occasion at the NDTV news office, whether it is birthdays, redundancies, promotions, farewells or even a particularly stressful day of work, everything can be assuaged with the right amount of sugar-rush, replicating the dopamine high, attention deficit disorder (ADHD) ailing broadcast television in the world’s largest democracy.

While We Watched premiered at Toronto International Festival (TIFF) in September last year and is now showing across theatres in the United Kingdom. The film premiered at Curzon Soho in London on the 10th of July, the filmmaker and journalist were present for a Q&A session after the film