On Global Day of Parents, a voyage into the wondrous world of homecoming stories

“Children begin by loving their parents; as they grow older they judge them; sometimes they forgive them,” said Oscar Wilde, in the kind of pretentious witticism that children of today are prone to ape, philosophizing about their parents’ folly with glee. Perhaps being a parent is the greatest sin. In an already overpopulated world that is hankering for a trace of the earth, who dares to bring about another of one’s kind, rendering them an afterthought in the late pages of the fall of civilization?

And the parents are punished for this sin, too: children are seldom easy, manageable people. Wilde, so bright and epitomic with his cleverness, actually adored his parents, and considered himself a source of shame to their name. In his role as a hypocrite and a wiseacre, he comes to define much of how modern children think about their parents: so great! And yet…. On Global Day of Parents (June 1), here is a look at some books, films and TV dramas that deal with the theme of parenthood, and the meaning of home, to excellent effect:

Film: Kapoor & Sons (2016)

In one of the best Hindi-language screenplays of the last few years, co-writer and director Shakun Batra continues to build on the lives of Kapoors. In his debut feature, Ek Main Aur Ekk Tu (2012), he gave us clear signs of a refined, if Western, palate: the protagonists’ struggles are very much varnished and first-world.

He builds on his rare skill of bridging the jet set crowd of his movies to his audience in this screwball comedy, set in Tamil Nadu’s picturesque Coonoor. He ties frayed threads together: these are soured relationships between brothers, between parents and offspring, between parents, between neighbours. The story could be about how death and its looming possibility brings us closer to our loved ones.

Their family is marked by absurd, impossible dysfunction, yet in several scenes it seems to be very much our own. A sequence with a plumber, where the parents are arguing about something really fundamental to their marriage, also has two brothers in fisticuffs about something really silly. The plumber gawks around. Conflict in families is rarely unidimensional: the weft of affection and self-interest obscure our rationality. There are favourites and there is envy.

Sometimes coming back home, Batra argues, does a number on you. This is especially relevant if home is an island of bitter memories and uncomfortable secrets. Dying, then, is erasure. A terminal end to the frayed fabric of a life. Their dying grandfather brings them together, first in form, then, through independent tragedies, in spirit, and all the unending mundanities shiver away.

Film: Manchester by the Sea (2016)

Manchester by the Sea is a geographical location. It is where Lee Chandler, our hero, returns to face his demons. It is also a zone of the mind. Guilt and the forward nature of time poison our souls. Lee’s crime is that he burnt his children to death by accident, and lost everything in the process. He now spends time as a handyman, drinking his sorrow away. Death beckons. His brother, already sick, is no more. He has a moody, teenage son. Together, he is brought back to life.

It is a “found family” trope film about people who are already family, but not quite. Lee’s return to the small, snowy town is not welcome. He is still known as the redoubtable filicide, an unstable drinker. Family, however, is about forgiveness, even though one may lack it oneself. Lee’s poor wife, now divorced and remarried, has all the reasons to hate him, yet when she sees him with emptiness in his eyes, she breaks down. “You can’t just die!” she says. “I can’t beat it,” Lee confesses. He can’t stare into the demons’ faces any longer, because the guilt is crippling.

It makes him see dead children, it makes him self-sabotage everything. His nephew, so hormonal and hotheaded, realizes his uncle can never call this place home, for it’s haunted by an unforgivable past. They find family in each other: two orphans who are scared of movement in life, and are attached to their hometowns for some semblance of normalcy, when they both know there is simply nothing there. A deeply unsentimental, yet melodramatic, screenplay won Kenneth Lonergan his first Oscar at the 2017 Academy Awards.

TV drama: Mad Men (2007-2015)

It tells you everything and nothing about the protagonist, the fancily-named Donald Draper, when you learn he once took his kids to a rundown whorehouse for nothing but vindication and pontification. Mad Men is about a man who works in advertising. Its central arc is about how Draper, he of a broken childhood, is unable to ever be himself. Brought up in a brothel and abjection, he has metaphysical scar tissue, a walking vacuum of seduction and self-pity.

His children worship him. This is the core: he has convinced his children of his unwavering innocence. He is the man; his bulging arms are monkey bars for his children. He is kind and observant and funny. To his wife, however, he is an asshole. How he keeps the two separate is a testament to his skill in advertising, or lying perkily. The children are quick to find fault with the mother. “Did you make him leave?” his daughter asks when her parents go separate ways.

Also read: White House Plumbers review: A goofy, sharply satirical ride through Watergate scandal

A few years later, his daughter walks in on her father sleeping with a neighbour. Draper lunges after her as she runs in a marble corridor, half-crying. She never forgives him. Draper later takes his kids to a defunct whorehouse. As Judy Collins’ song Both Sides Now floods the background, Draper says some words. “This is where I grew up.” He has come home to “a bad neighbourhood”, as his son calls it. Is this his attempt to explain to his daughter why he is the way he is? She stares up at him, and he looks back. Draper has had a tough life, his daughter realizes. He may truly be a rare miracle of the American dream.

Book: The Silver Linings Playbook (2008) by Matthew Quick

The heavens are opening up: a son is home. He’s been away at a mental health facility for years. He had punched his colleague from work — he’s a substitute teacher, for history — almost dead because he found his wife having sex with him. Quite literally. A traumatic incident. He’s now convinced that he can get it all back. What I want to talk about is not how Pat Peoples is cured of his delirium, but how his parents help their 40-something son get back on his feet.

Reading this book is simply sublime. The parents have their troubles, yes, and their marriage isn’t rock solid. But in all the hysteria they make room for their son, who has suddenly become the worst child ever, too happy for an adult, too violent for a child. There is so much love in the community. Sometimes coming home can be quite frankly fantastic.

The tale is enchanting because every chapter is a reevaluation of what parents are supposed to, or burdened to, perform for the sake of their children. In a society where you are expected to get out and make your own living, what do parents do when their quiet retirement is magnificently disturbed by a son running amok, like flying a hand through marvelously arranged quietude of old age. They take him under their wing. They are kind people, and they love their weirdly upbeat son.

His mother drives him like a sick puppy to his therapist, who tells him only Pat can help Pat. It is really the temperament of a city, the city as a person, that guarantees what we become. We walk around with the city’s earth inside us, because we took root there, and we carry chips on our shoulders.

In the end, Pat turns away from doing something he would definitely have done had he not found such a community back home: he backs away from his ex-wife. He and his brother watch from a distance, covertly in a still car, as the lady and her new husband sun themselves and their kids. Pat doesn’t even think of talking to her. He has moved on. He’s a calmer person. The community is his therapy. That is the palliative power of society that takes “it takes a village” to heart.

Also read: India at Cannes 2023: From Aishwarya Rai’s silver hood to Anurag Kashyap’s Kennedy

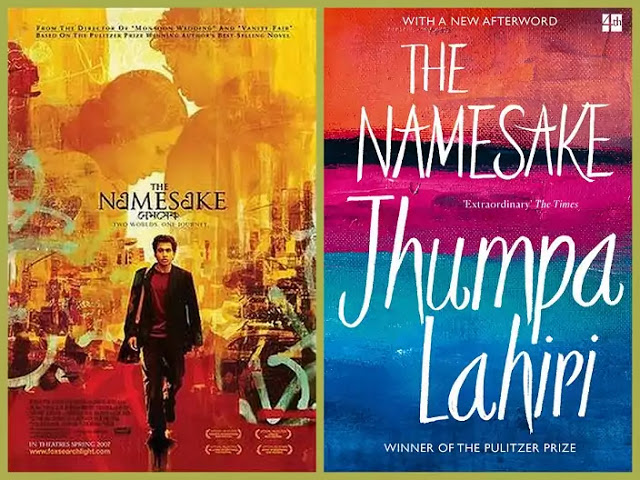

Book: The Namesake (2003) by Jhumpa Lahiri

Jhumpa Lahiri’s debut novel unfurls with an exquisite tapestry of familial bonds and the perennial desire to return to the proverbial hearth. Gogol Ganguli, the novel’s central figure, emerges from the cultural cauldron of his Bengali immigrant parents and embarks upon a voyage both profound and poignant.

Through the prism of parenthood, Lahiri captures the intricate dance between tradition and assimilation, deftly revealing the delicate fabric of identity that children of immigrants navigate. Gogol, like an intrepid traveller, wrestles with the weight of familial expectations bestowed upon him by his parents, Ashoke and Ashima.

I have always found it comical how children, forever, have blasted off from their homes to go to college. The further, the better. A meditative escapism of sorts, where to find new roots you have to uproot yourself first. Gogol is named by his father after his favourite author. The name is odd, and Gogol abandons it. In the process he also severs ties with his father, and spirals around the magnetic awe of America, not a child of immigrants.

To people like this, second generation immigrants, what is home? Debate around the achievements of NRIs has formally concerned itself with whether we can really claim their success as our own. Where does one continent end and another begin? A constant renegotiation of our social and cultural affinities is in order, where what makes our parents whole and truly themselves feels so foreign to us, a memorandum of a bygone era, their advice rendered completely, appallingly obsolete.

All of adulthood is realizing we are iterations of our parents. After years and maybe a decade wading through the hero’s journey, we arrive at a plateau of platitudes. It is the same playbook we’ll try to hand down to our successors, and who, when we’re not looking, mock us, tear us asunder for our blithe disregard for the rigors of a modern world. An ouroboros of pride and shame. Lahiri’s own personal history informs much of this tussle, which is not so much about foreign lands and a nostalgic gripe for one’ swades, but a search for what feels like home.

It is geographically independent: it could be a person, a nook of one’s neck and shoulders, a collapsing of arms around a formidable sense of joy and loyalty. When his father dies, Gogol rushes through the motions. The vacuum sucks him in. The novel ends with him returning to a book of Nikolai Gogol’s stories, a gift from his father. One can see Gogol embracing his roots again, but also mixing his origins, amalgamating the soil of continents. Home is where the heart is.

Film: You Can Count On Me (2000)

Even before Mark Ruffalo took over as Hulk in the superhero movies, he was green behind the ears. He skulked around, a vagabond thespian, spinning atop theater props in 1996. This Is Our Youth: the play was written by a nobody, Kenneth Lonergan. Four years later, Lonergan was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. That was his cinematic debut. It also stars Laura Linney, a champion of the troubled onscreen sister (see The Savages, 2007). And Mark Ruffalo comes through.

You Can Count on Me is about orphaned siblings, now all grown up. The sister, because she is the elder and so it is natural, nurtured the brother like a parent, but wasn’t able to do it well enough. Why? Because she’s a child herself. When young the sister is described as “wild”, the more mischievous one. Alas, parenting sobers you.

Also read: Interview I Why Tovino Thomas did not want to do Malayalam blockbuster film 2018

The grown sister, portrayed by Linney, is a placid person. The sibling who has to grow too soon is a familiar, effective trope, as it is rife ground for the human drama of conflict between one’s sense of self and the simultaneous ego death of selfless caring. What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993), the movie and its title, capture the theme expertly: caring for a mentally challenged sibling is “eating” at the elder brother’s sanity. In essaying co-dependence and semi-parenting traits among siblings, Glass Castle (2017) also comes close.

The two meet again. Years have gone by. The sister is breaking away. Lonergan avoids the cliched rhetoric of parents-as-real-people to focus on the hometown as a character. The original geographical bounds of one’s life, now constricting. Especially in more homogenous communities — think smaller towns, kasbas, and hamlets. A constant source of shame and knowing nods. Hat tips to one’s embarrassing skirmishes.

The movie ends with the brother leaving on a bus, never to come back again. Linney’s character cries at this delayed end of childhood, and she realizes she is to now take stabs at improving her life on her own with nobody else to show her the ropes. The siblings had so far parented each other in their own little ways, but there’s an end to that.