Leena Manimekalai: Cis-het actors think it's exotic to play LGBTQ roles

Independent filmmaker and poet discusses LGBTQIA+ portrayal in films, their concerns and her own connect with the queer community, where she feels she belongs the most

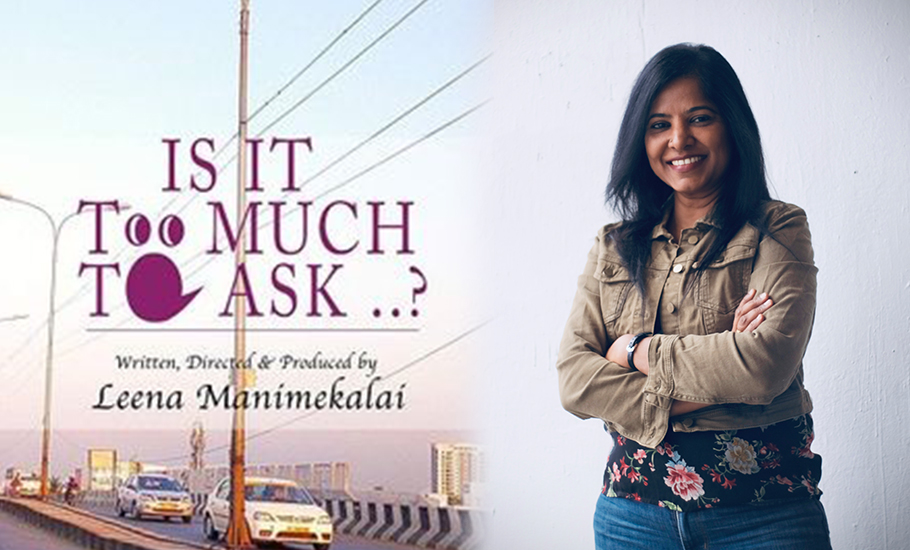

If you are a single woman, a non-vegetarian and a transgender, your chances of trying to rent an apartment in Chennai whittle down to zero. Leena Manimekalai’s 2017 documentary, Is it too much to ask? (streaming on MUBI as part of Pride Month), delves into the frustration and hopelessness faced by two transwomen, Angel Glady and Living Smile Vidya or Smiley, as they try to rent a house in Chennai. They long for a roof over their heads to feel safe but they draw a brutal blank.

This documentary, which won an award at the Singapore International Documentary Festival, and earned a special mention at Film South Asia, is quirky, tragic and a biting satire on Indian society’s deeply entrenched fear and prejudice towards transgenders.

Life for a LGBTQIA+ in India

Five years after the film was made, The Federal caught up with the redoubtable Leena Manimekalai, independent filmmaker and poet, to talk about if life has changed for the better for the LGBTQIA+ community, their portrayal in films, the impact of OTT and her own connect with the queer community, where she feels she belongs the most.

“If I had not found refuge in poetry and cinema, I would have taken my life a long ago (laughs). Art, writing and cinema is my home, if not for this home, I would have been dead by now,” says Manimekalai on a Zoom call from Canada, where she is pursuing her masters in fine arts in film at York university. This self-taught film director picked up a lot of critical appreciation for her second feature, Madaathy, an Unfairy Tale, which told the tale of the horrors heaped on a lower caste community, the Puthirai Vannars, in Tamil Nadu. She is currently working on her thesis feature film, Kaathadi (Kite), which she calls as “a love memoir of a brown queer woman”.

Art and politics merge in the world of this Tamil filmmaker, poet, and activist. Known for her “intensely candid takes on society’s failings,” Manimekalai’s diverse filmography gives a voice to the marginalised. In her work, she follows the legacy of Chantel Akerman, Maya Deren, Agnes Varda, Cheryl Dunye and Julie Dash, she says.

Also read: Amazon Prime Head Aparna Purohit interview: ‘OTT has broken all barriers’

India taking baby steps

Not much has changed in India since the time Manimekalai made that film in 2017, she says. India is still taking “baby steps” in improving the lives of transgenders. “We have increasing visibility in the media, we have laws supporting LGBTQIA+ community, civil society makes an effort to welcome transpeople into the mainstream, Tamil Nadu even has a separate welfare department for transgenders and we have a voice in politics too,” she says, citing the example of Narthaki Nataraj, trans classical dancer, who became a member of the State Development Policy Council of the Tamil Nadu government.

“Family acceptance and assimilation into mainstream society, however remain major challenges,” says the filmmaker, who currently identifies herself as a pansexual, which means she is attracted to a person sexually, romantically or emotionally regardless of their sex or gender identity.

She continues, “Family ostracisation is very real, which no one is talking about. That acceptance is very lean, trans people are thrown out of their families at the very beginning. Equal to the noise around the LGBTQIA+ community, there is very little assimilation in mainstream society. If a lesbian couple in Chennai decides to live openly, I think, their assimilation will be very complex. Trans people still struggle to get a decent job and a decent home.”

That’s one of the key reasons her two protagonists in Is it too much to Ask? left India, she says. Exiled, she calls it. “They were tired of being pushed to the margins, it was important for them to be seen as a woman and not through the transgender lens. That is not happening in India as yet,” she says.

Smiley, whose life was made into a National Award winning Kannada film, Naan Avanalla Avalu (‘I’m not him, I’m her’), is a gender refugee still seeking asylum in Switzerland. While Glady has been accepted in Toronto, feels equal and works at an Apple Store, and above all, is able to rent a house and dress the way she wants.

Also read: How female deities helped foster caste violence in TN

Fascinated with the medium of cinema, Manimekalai, who studied engineering and grew up in Chennai, made her debut film Sengadal: The Dead Sea in 2011 on the dispossessed Sri Lankan Tamil refugees at Dhanushkodi. She subsequently made a few documentaries, including the documentary White Van Stories, on Sri Lankans who went missing during the terrible civil war, which was broadcast on Channel 4. In 2022, she was selected by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) as one of their Breakthrough India talents, making her outlier work more visible. She is now poised to enter the big league, as she signs a five project deal with a studio and streaming platform to make a web series, a feature, an international collaboration and more.

On portrayal of LGBTQIA+ in cinema

Down the ages, Indian cinema has not been kind to the portrayal of LGBTQIA+ characters. From Amitabh Bachchan, Kamal Haasan to Ranbir Kapoor, all have donned a female garb to draw laughs, as a figure of ribaldry. But, slowly, awareness has crept in and Bollywood especially has been pushing the envelope with mainstream actors like Rajkummar Rao and Sonam Kapoor comfortably essaying the role of gays.

Manimekalai disagrees. “I like to say it is changing but it is not,” she says, adding that trans people are brought in on screen as a form of tokenism. “Earlier, you had a Tamil item number, a hero’s sidekick who will be a comedian, now we have transgenders in films. That is disturbing,” she adds. Though, she loved Neeraj Ghagwan’s Geeli Pucchi (‘Wet kiss’, Netflix) (Konkana Sen and Aditi Rao Hydari), calling it the best ever work on lesbian love that has come out of India and Badhaai Do (‘Congratulate’, a gay man marrying a lesbian to keep the family happy). “It’s great for a mainstream movie like Badhaai Do to make it work,” she says.

On Tamil film Super Deluxe, which famously had Vijay Sethupathi playing a transwoman, Manimekalai has mixed feelings. She felt that film exoticised queer and ‘it had a certain voyeuristic gaze’. “When the transwoman’s child says, ‘I have two mothers’, it moves you. But that violence scene in the police station, the lensing was voyeuristic entirely. A bad portrayal of a community is a violence perpetrated on the community, it does more damage and should stop. I feel directors and actors should stop,” says Manimekalai.

She slammed Vignesh Sivan’s short film in the anthology series Paava Kaadhigal, which was based on a lesbian couple. “Not talking about the subject is better than having half-cooked narratives. I feel, there are a lot of gaps in understanding on how to portray gay love. You insult an entire community with your ignorance and you dare to put it on screen. Geeli Pucchi and Badhaai Do are great LGBTQIA+ arrivals in Indian cinema, but we still have a long way to go,” she says.

Also read: A first in Bollywood: LGBTQiA+ film with a queer actor in the lead

Manimekalai strongly believes trans people should play trans roles. “When you cast a heterosexual male in a trans role, you are reinforcing the stereotype that transwomen are not women. Actors think it is exotic to do such roles but they are doing more damage. I don’t know even one single hit superstar who has not done a transwomen role. Heterosexual female actors should ethically refuse to do these roles,” she says.

On OTT having opened doors for LGBTQIA+ films

“As LGBTQIA+ becomes a part of the larger community, commerce enters the picture. Consumerism and capitalism has started to embrace it. But, it’s also true I’ve never reached such a wide audience before with my films. OTT is opening doors for Indies. There is a change but we have a long way to go,” says Manimekalai. Six of her works are currently being streamed on MUBI as part of a spotlight on her as a director.

For a cinephile like her, she finds MUBI a good resource. “To have my work on MUBI is such an honour. It’s very uncompromising in its choice of spotlighting an independent director. I like the way they present a filmmaker, they are home to me,” she says.

Leena’s choice of LGBTQIA+ movies to watch

Chantel Akerman’s Je Tu il Elle is the textbook film for me on bisexual women. I recommend Dog day afternoon, Cabaret, Greenbook, Brokeback mountain, Milk, Portrait of the lady in fire, Moonlight, Paris is Burning, Tangerine, Fantastic woman, Rafeeqi and almost all of the Pedro Almadover films.

Chantel Akerman’s Je Tu il Elle is the textbook film for me on bisexual women. I recommend Dog day afternoon, Cabaret, Greenbook, Brokeback mountain, Milk, Portrait of the lady in fire, Moonlight, Paris is Burning, Tangerine, Fantastic woman, Rafeeqi and almost all of the Pedro Almadover films.

In her own words

“Queer is not just about sexuality. It is more about fluidity, today, I am questioning heteronormativity in everything around me – there’s bigamy in everything, in history, art, literature, thoughts, our very existence…I am against the conditioning of thinking in duality – good or bad, black or white. Queerness showed me to view life in a spectrum. It shows me the greys, and other colours. On subjects like decolonisation, patriarchy, capitalism, I find a lot of refugee in queer theories. It gives me a zone where I belong, or else I feel I am nowhere. With the queer community, I feel I belong. Queer is a sense of becoming, it makes me flow.”

“It was in Anthara Kanni, my first lesbian poetry collection in Tamil that I delved into Tamil folklore and rewrote it through a lesbian lens. I turned Tamil heterosexual folklore songs into female longings for another female. My purpose was to tell that queer had always existed in India for a long time. I took Alli Rani, the Amazonian beauty, a vehement hater of men, who ruled over the Pandyan kingdom, and imagined her as a lesbian queen. One part in the book is about Tamil traditions, while the second half concentrates on the international lesbian movement like the Pussy Riots etc. There was a major silencing of the book in the mainstream. Normally, I get a lot of critical reviews, trolling, witch-hunting and hate on one side, and awards on the other. It, however, became a handbook for the community. A girl from the smaller towns of Tamil Nadu found comfort in reading about lesbian love in Tamil literature – it gathered the gay community. That was good enough for me.”

“Yet, amid all this angst, I am still discovering how to be a queer in writing and in making films. Making films for me turns out to be a journey of healing, a journey of finding your community and sharing the narratives, which gives you reason to live.”