FRIEND, SON, MAN, MESSIAH

FRIEND, SON, MAN, MESSIAH

The Story of Kashmir’s integration with India

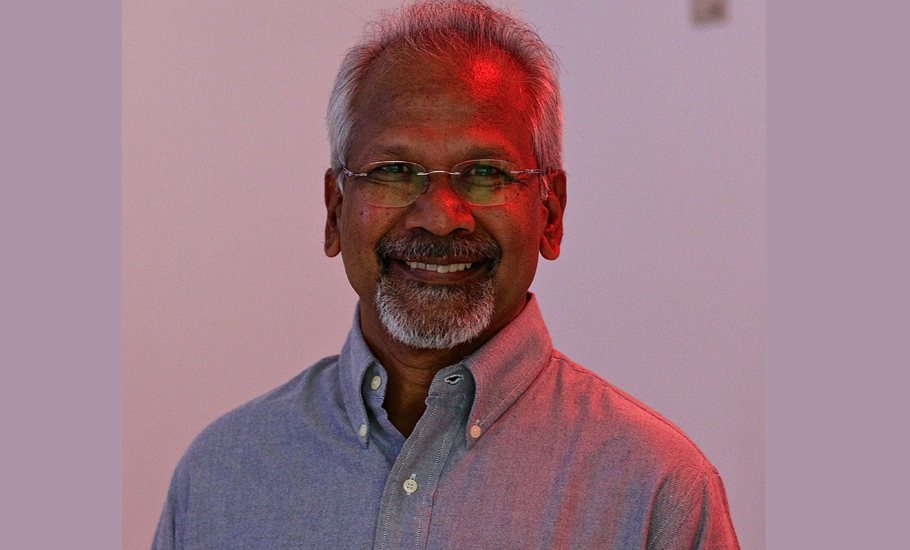

Thirty years since its release, Thalapathi strikes you as a rare form of star-driven popular cinema. It plays at familiar pitches to make something distinct, embracing and yet independent of genre must-haves, writes R Krishnakumar.

Uploaded 04 November, 2021

Video by Imaya

At 30, any film could be seen as closer to a transition point in the viewer’s imagination. It’s a fairly appropriate time for a rear-view take on how all those years have shaped its legacy, or in most of the cases, on whether or not it is worthy of scrutiny.

Mani Ratnam’s Thalapathi, a 1991 Deepavali release, features in multiple best-of compilations. The film is one of the more popular works of the director and the cinematographer (Santosh Sivan). It has its lead actor, Rajinikanth, in one of his most acclaimed performances and its music scored by Ilayaraja, in his last collaboration with Mani Ratnam, is still wildly popular.

This, arguably, is the most entertaining film to have drawn on Karnan’s story from the Mahabharata, the tragic story of a wronged son and his inner conflicts. One of the film’s prominent themes – the friendship between a mob boss (Devaraj is the Duryodhanan here, played by a charismatic Mammootty) and his trusted enforcer (Surya, played by Rajinikanth) – is extensively referenced in popular culture. Thalapathi is also a default pick for lists of Tamil films set around gangsters.

What, really, is its legacy? Thirty years since its release, the film continues to defy genre bracketing. It does have the staples and sweep of a star vehicle. It has the big, introductory action sequence for Rajinikanth, with bare fists, blinding rain and a rousing background score.

The songs are designed like slick music videos; one of them, Raakkamma kaiya thattu, featuring Sonu Walia with Rajinikanth, formalised the latter-day masala film tradition of the item song.

In its final act, the film also makes a fan-pleasing compromise to leave its hero alive; as a man who has reclaimed his honour and has by his side, the mother (played by Srividya) who abandoned him as an infant.

Thalapathi, produced by Mani Ratnam’s brother, the late G Venkateswaran, was the rare event film from the south of India which generated national interest. The hype was real. The budget and salaries (Rs 60 lakh was reported for Rajinikanth) hit headlines and a merchandise-driven promotion (on the street, you still see the Rajinikanth t-shirt with the film’s iconic, red title design) powered a long run-up to the release of what was billed as an entertainer packaged for Tamil Nadu’s biggest festival season.

Expectation, though, could be a tricky thing with Rajinikanth. The superstar’s last big hit, Dharmadurai (1991), was a formulaic festival release (Pongal) about a man from the village who reforms his two younger brothers lost in the big bad city. Mani Ratnam was coming on board after Anjali (1990), a film about an autistic child. The collaboration, exciting as it was, had also set off questions on what to expect.

The commercial compulsions attached to a big-ticket superstar film are a given but Thalapathi does not play entirely by that rulebook either. For a start, this is a Rajinikanth film without comedy. The romance, with Subbulakshmi (Shobhana), is unhurried, understated; when she leaves Surya, we see evening light fade around him as he stands, taking in another rejection, and watches. His relationship with Padma (Bhanupriya) is shaped by guilt. He has killed her husband and when he holds her baby in his arms, he fumbles – he knows that she’s looking.

Surya’s dilemma of having to pick sides at war which forms the core of his story is also treated with restraint. When Devaraj asks Surya why he was chosen over his half-brother, the response is plain – “yeanna nee en nanban” (because you are my friend). That sounds just about right. That sounds enough.

Thalapathi stylises violence and adopts a simplistic treatment of vigilante justice and power conflicts between the state and the criminal. There’s a distanced-outsider tone in the writing of a scene where the two sides are engaged in truce talks, at the office of the district collector (Aravind Swamy in his debut).

The tension is not raw, the build-up is orchestrated but this is neither a celebration of the heroic swagger, the kind we’ve since been conditioned to accept as a genre marker. It appears to straddle two sensibilities and still, manages to hit the right notes and hit them well enough to create something distinctly entertaining.

A belligerent Surya takes on a top cop – his line, “thodraa paakkalaam” (touch me and you’ll see), has morphed into variants of the mass-hero dare in Tamil films – and Devaraj, after calmly defending his right to operate as a parallel justice system, leads his men out.

The space is limited; the men are sitting around a table and they are just talking. The tension is mostly understated, with the pauses and general civility of proceedings building up drama to the eventual meltdown. The background score burns slow, the dialogue crackles but doesn’t stretch beyond what is sufficient and yet, there’s something about the staging that makes it a solid piece of masala filmmaking.

The consistency with which Thalapathi finds this meeting point of sensibilities, something the modern-day fan would call a “class-meets-mass” space, perhaps, drives the film’s biggest legacy.

Mani Ratnam had already brought in new aesthetics to Indian popular cinema with Agninatchathiram (1988) but Thalapathi was an upgrade, in scale and star power. Rajinikanth’s previous release, Naattukku oru Nallavan (1991), had tanked but he was still unchallenged at the box office. For Thalapathi, Mani Ratnam’s only film with Rajinikanth, the writer-filmmaker wanted the superstar as the actor he had admired. The actor who had turned up in films, including Mahendran’s Mullum Malarum (1978).

Thalapathi also remains the last real meeting point for the star and the actor. Suresh Krissna’s Baasha (1995) has since elevated the Rajinikanth cult, making a return for the actor increasingly improbable. Pa Ranjith would later make radically different Rajinikanth films, Kabali (2016) and Kaala (2018), but there, the filmmaker appeared focused on mining the big-ness of his star to take the film’s politics to a wider audience. Thalapathi, in contrast, also has the star as an actor, with the high points – one of them is the scene where Surya hears about his birth and rejection – making us wistful of this actor’s trajectory in a parallel, imagined timeline.

The film’s title is now almost appropriated to another star, Vijay. The actor started out as Ilaiya Thalapathy (young commander), before shaping his own course as Thalapathy, the Box Office force he is now. He started using the moniker, in the mid-1990s, as a fan nod to Rajinikanth, a move that also established him as heir-apparent to the original Superstar.

What Thalapathi leaves behind is often reduced, rather unfairly, to the argument that it doesn’t fit well into the Rajinikanth or Mani Ratnam universes. The film was a commercial success but did not match the superstar’s blockbuster standards of the 1980s and 1990s and the critical consensus was of a satisfying watch, falling a touch short of its promise.

The evolution of the star culture in Tamil cinema and the rules that shaped patterns of the south Indian mass-hero film, over three decades, place Thalapathi in a new context. The film navigates its creative and commercial compromises well enough to hit a middle ground that the modern massy film could not, or would not attempt to, find.

Thalapathi is rarely accorded the top rung in the Mani Ratnam oeuvre but is ageing better than some of the filmmaker’s more political, less mainstream work. Reductive reviews of the film called it “classic kitsch”. Thirty years later, the film has found its place as a standalone piece – an intelligently staged, toned-down retelling of an epic story, put together in a one-off convergence of styles and sensibilities.