‘Beyond Utopia:’ A harrowing account of how a ‘defector’ flees North Korea

Imagine this: you’re a prisoner in your own country. So, you make plans to flee. For this, you bribe a border security personnel, and put your faith in a ‘broker’ from a neighbouring country who can’t be trusted. After all, they don’t see you as a person, you’re just ‘money’ to them. You cross a river, scale a mountain range, navigate through dark forests. Cross the borders of three countries (allies of your nation), surrender in a country that’s not ‘friendly’, and then get deported to a place where you can live with some semblance of freedom and dignity. This is the life of a ‘defector’ from North Korea, and as much empathy one might have, it’s close to impossible to imagine the physical and psychological obstacles one has to overcome to flee one’s country.

Most of us might have seen a Ted talk by those managing to escape North Korea’s totalitarian regime, recounting the horrors of their everyday life. However, nothing prepares you for how arduous Madeline Gavin’s Beyond Utopia is going to be. It doesn’t matter how many newspaper reports you’ve read, or video clips you might have chanced upon of a North Korean ‘defector’ — the first-person vantage point makes it all the more urgent and primal.

Victims across the border

Gavin’s film finds victims on either side of the border. There’s the Roh family — staring at lifelong banishment after being named in a list punishing the kin of defectors. The family includes an 80-year-old grandmother, two tiny daughters and a couple. Realising they would starve to death, the family makes a run for their lives, evading the border patrol, ending up at a farmer’s house on the China-North Korea border. It’s at the farmer’s home that the family is told about a pastor in South Korea, who helps defectors by arranging to pay ‘brokers’ to escort them towards safe passage. In touch with a Christian missionary, who can afford to undertake such humanitarian initiatives, Pastor Kim spends most days fielding phone calls from relatives of those wanting to get out of North Korea.

Also read: Sundance 2023: ‘Magazine Dreams’ is a raw, riveting study of isolation and delusion

Pastor Kim is also approached by a mother named Soyeon Lee, who spends years convincing her teenage son to defect. In touch with a broker, Soyeon is advised by the pastor to buy new clothes for her son, so that he looks like a ‘South Korean’. In a moving scene, Soyeon bemoans looking at the new clothes she’s bought, wondering if they’re the right size. “I don’t know how much he’s grown,” Soyeon says, shedding a tear for her son who she hasn’t seen in a decade.

The open wound

Gavin’s film keeps cutting between the two rescue missions in real time, while also touching upon how Kim Jong-un, the Supreme Leader of North Korea, came to inherit his ‘hermit kingdom’, and how much worse he’s made it. How propaganda has trickled down into mathematics text books for kids, brain-washed about the ills of the outside world to such an extent that they end up believing their own bare-bones existence is ‘Utopia’.

It doesn’t matter that the people are working within an inch of their lives, have barely any food at the end of the day, and where civilians starve to death on the street, and no one bats an eye. At one point in the documentary, Pastor Kim’s wife (also a former citizen from North Korea) tells the film crew how she fell in love with him because ‘he had a belly’, something she had grown up associating with Kim Jong Il and therefore by extension… excellence. In the same scene as she’s serving dinner, for the three of them – she casually quips how this spread could last them a whole week in North Korea.

Also read: Sundance 2023: ‘Eileen’ is a compelling portrait of a woman’s descent into darkness

In a world where North Korea’s widespread oppression is such common knowledge that it doesn’t even get a second look, the defectors mirror the open wound at the heart of this unforgiving regime. While the Roh family remains on edge through long car rides, crossing the jungles in Vietnam where the war was fought (and probably infested with landmines), and precarious boat rides across rivers, Soyeon frantically tries to call someone back to get the latest news about her son’s attempted escape. There’s no network in North Korea, so only if you get close enough to the border is if the call would maybe get through, with the voice remaining choppy. When Soyeon senses there might be bad news coming from the other side but the call remains unintelligible, it is one of the most harrowing scenes to witness.

Freedom, taken away

In another chilling moment, the grandmother of the Ro family is asked by the documentary crew to speak freely of her experiences while growing up, and she automatically starts regaling what a great nation she comes from, and what a kind, dynamic leader Kim Jong-un is. When her daughter-in-law tries to explain to her that she can be ‘truthful’ to the documentary crew because she is not going to get hurt because of it, there’s a moment of disbelief in her face and yet she’s suspicious of how she might be punished for it.

It’s a particularly frightening moment to see how you can alter a human being’s fundamental impulses, if you take away their freedom. The scene ends with the grandmother telling the crew that the regime teaches all kids to refer to Americans as ‘American Bastards’ because they want to drill it deep into their belief system. However, she couldn’t believe that the crew filming her was also American. “It makes me wonder about all the other lies I’ve been told throughout my life,” she cries, and it’s the most antagonistic thing she’s able to say against her oppressors.

Also read: Sundance 2023: ‘Fair Play’ is a stellar, breathless indictment of the ‘nice guy’

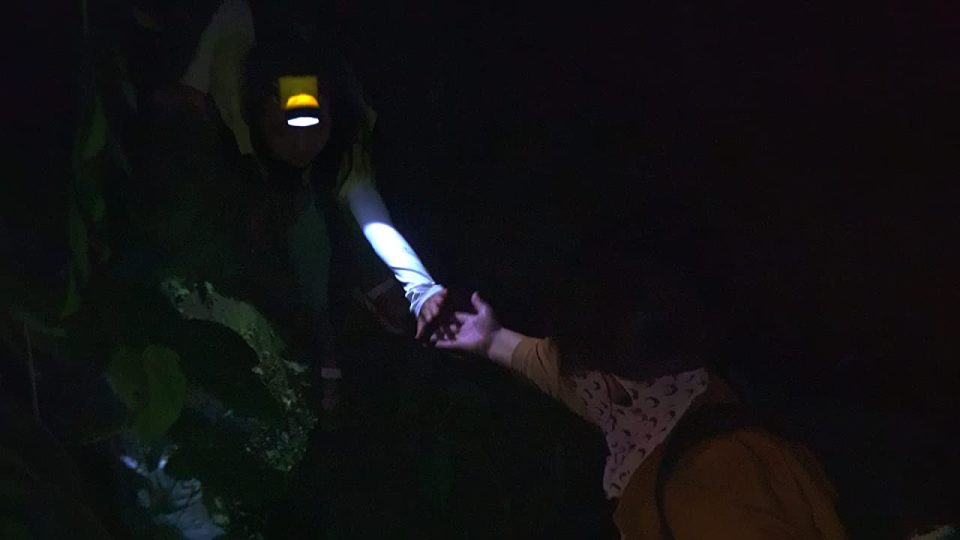

There could be a few ethical questions around Gavin’s film given how it doesn’t delve deeper into Pastor Kim’s motivations behind helping the people, beyond the perceived humanitarian grounds. Does the Catholic church support these initiatives (involving a significant amount of money to be paid to the several brokers, and bribes to personnels in law enforcement) without wanting anything in return? Also, a majority of Gavin’s film (especially portions in the mountains on the North Korea-China border, the forests of Vietnam) are shot by brokers and Pastor Kim accompanying the families on their perilous journey. So, even though it does have the rawness of some never-before-seen footage, it still doesn’t have the flourishes of a film like, say, Navalny (2022).

The collective trauma

Despite these questions, there’s absolutely no question that Madeline Gavin’s Beyond Utopia goes into places no previous film has dared to go. An American crew handing over cameras to the people escorting a family with danger looming over them is probably not the best proposition. But it could be argued that embedding an actual crew with the family, as they undertook the journey through three different countries, could have possibly sealed the fate of the Roh family. By showing the physical hardship of North Korean defectors in granular detail, it underlines the collective trauma that North Korea and its fellow communist allied nations like China, Vietnam and Laos have inflicted on people trying to escape.

Beyond Utopia almost makes us value our freedom — something dear to us, which we take for granted. It’s only probably a film like this that can knock some sense into those middle-aged (and primarily middle-class) Indians — who whimsically say silly things like there’s “too much freedom” and how we “deserve to live under a dictatorship”. Only watching a film like this, where they come face-to-face with the collective trauma of hundreds of human years’ worth of oppression, will they realise how they don’t have the faintest idea of what they’re wishing for.