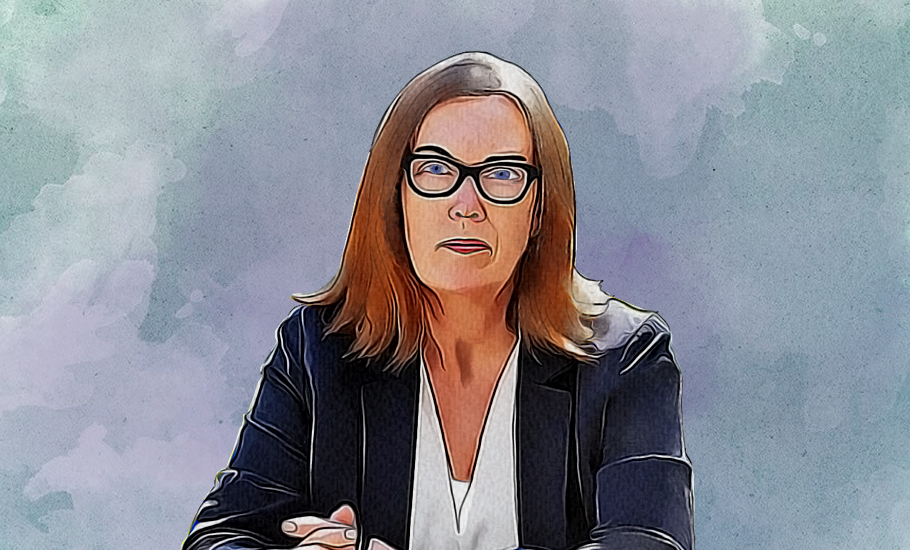

Prof Sarah Gilbert: The shy scientist who became a vaccine superstar

Friends and colleagues describe Prof Gilbert as a conscientious and determined person. 'Sometimes I think she can be quite shy and reserved to people,' one of her PhD students told Profile. 'Some colleagues I had at the Jenner Institute always were a little bit intimidated by Sarah. But when you get to know her and you spend time with her, that’s not the case at all'

In the last week of June a Twitter clip – a little more than a minute long – ricocheted around the world. It was June 28, 2021, the first day of Wimbledon. Tennis’ marquee event was returning after a gap of one year. The video shows a modest, bespectacled woman in a red jacket, sitting in the Royal Box, being given a prolonged standing ovation by the spectators. She looks embarrassed but graciously acknowledges the applause with a nod of the head.

Prof Sarah Gilbert could have leapt on to the Centre Court and run a victory lap that day and no one would have begrudged her – such is the respect and affection for her in the minds of the public. But the designer of the Oxford vaccine – the most famous scientist in the world today, credited with saving millions of lives – is happy to let her work speak for itself.

Standing ovation at Wimbledon’s Centre Court for Dame Sarah Gilbert who designed the Oxford COVID vaccine.

Very moving. pic.twitter.com/q4NosT19eN

— Joe Pike (@joepike) June 28, 2021

Sarah Gilbert was born in Northamptonshire, England, in April 1962. Her father worked in the shoe business while her mother was an English teacher and member of the local amateur operatic society.

She graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in biological sciences from the University of East Anglia in 1983, then moved to the University of Hull for her doctoral degree, where she investigated the genetics and biochemistry of the yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides.

While at Hull, according to the BBC, Gilbert briefly considered giving up science altogether. At UEA, she was energised by the diversity of thought and experience in the department, but at Hull she found the single-minded focus on one topic not to her liking.

“There are some scientists who will happily work more or less on their own on one subject for a very long time… That’s not the way I like to work. I like to try to take into account ideas from lots of different areas,” she told BBC Radio 4 earlier this year.

“I did consider leaving science at that point and doing something different.”

Eventually though she decided to have “one more go at a scientific career” and stick with the PhD. “I needed the income,” she said with candour.

Having completed her PhD, Dr Gilbert worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the Brewing Industry Research Foundation, before moving on to work in human health.

Dr Gilbert had never meant to be a vaccine specialist. Yet by the mid-1990s, she was in an academic job at the University of Oxford, looking at the genetics of malaria.

Also read: Even mild cases of COVID leave a mark on the brain, study finds

She quickly rose through the ranks, becoming a professor at the university’s Jenner Institute and setting up her own research group in a bid to create a universal flu vaccine.

In 2014, she led the first trial of an Ebola vaccine. And when the Mers – Middle East respiratory syndrome, or camel flu – virus struck, she travelled to Saudi Arabia to try to develop a vaccine for this form of coronavirus.

Prof Gilbert and her colleagues were getting ready for the second trial of that vaccine when, in early 2020, COVID-19 emerged. She realised that she might be able to use the same approach, and, within a few weeks, she and her colleagues had created a vaccine that worked against the new pathogen in the lab.

The first batch of the vaccine went into manufacture by early April, as the testing regime expanded. “From the beginning, we’re seeing it as a race against the virus, not a race against other vaccine developers,” she said. “We’re a university and we’re not in this to make money.”

On December 30, 2020, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine she developed with the Oxford Vaccine Group was approved for use in the United Kingdom.

Friends and colleagues describe Prof Gilbert as a conscientious and determined person.

“Sometimes I think she can be quite shy and reserved to people,” one of her PhD students told Profile. “Some colleagues I had at the Jenner Institute always were a little bit intimidated by Sarah. But when you get to know her and you spend time with her, that’s not the case at all.”

Earlier this year Prof Gilbert was recognised in the Queen’s birthday honours. She received a damehood for services to science and public health in COVID vaccine development.

In August she received a recognition of a different sort: Barbie maker Mattel created a doll of the scientist. Her Barbie was one of six to honour women working in science, technology, engineering and maths.

“I am passionate about inspiring the next generation of girls into Stem careers and hope that children who see my Barbie will realise how vital careers in science are to help the world around us,” Prof Gilbert said when told of the “very strange” gesture on the part of the toymaker. “My wish is that my doll will show children careers they may not be aware of, like a vaccinologist.”

Prof Gilbert continues to make public interventions and advocate for vaccine equity around the world.

In a recent letter co-written with Dr Richard Hatchett, the chief executive of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and published in Science Translational Medicine, the professor said: “No one is safe until we are all safe… As the world grapples with the spread of the Delta variant, it is more crucial than ever that we do not forget the lives that could be saved by administering first and second doses to the most vulnerable populations worldwide and the opportunity that the global distribution of vaccine provides to protect all of us by reducing the selection of further Sars-CoV-2 variants.”