- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Why Tamil Nadu failed to document heroics of women in stone

Legend has it that in Tamil Nadu’s Madurai lived a woman named Nalluthayammal who killed herself immediately after delivering her baby. It is believed that when Nalluthayammal went into labour there was no one to help her, and so her father helped her deliver. Even though the delivery was smooth, the guilt weighed heavily on her. Scared how she would face the society, Nalluthayammal died...

Legend has it that in Tamil Nadu’s Madurai lived a woman named Nalluthayammal who killed herself immediately after delivering her baby. It is believed that when Nalluthayammal went into labour there was no one to help her, and so her father helped her deliver. Even though the delivery was smooth, the guilt weighed heavily on her. Scared how she would face the society, Nalluthayammal died by suicide after killing her new-born. Buoyed by grief and guilt, the father too killed himself soon after.

Today, a temple stands in honour of Nalluthayammal, housing a stone structure representing her.

“A small temple has been raised in memory of the woman who killed herself out of shame. As there was no woman to help her during delivery, her father assisted her. But she decided to kill herself and the child as she was worried over how to face the comments that the society will make. The father also kills himself after the death of the daughter and her child. This folklore is very popular among the residents of Madurai. Now, people offer prayers at the temple to ensure safe delivery and other worldly pleasures,” sculpture expert P Devi told The Federal.

Such ‘heroine stones’ dot Tamil Nadu even if not in the same abundance as ‘hero stones’. The mismatch is not only in their sightings. Hero stones are also more richly documented than heroine stones which are conspicuously absent from the pages of history. Devi has identified about 20 structures in various parts of Madurai in the last three years.

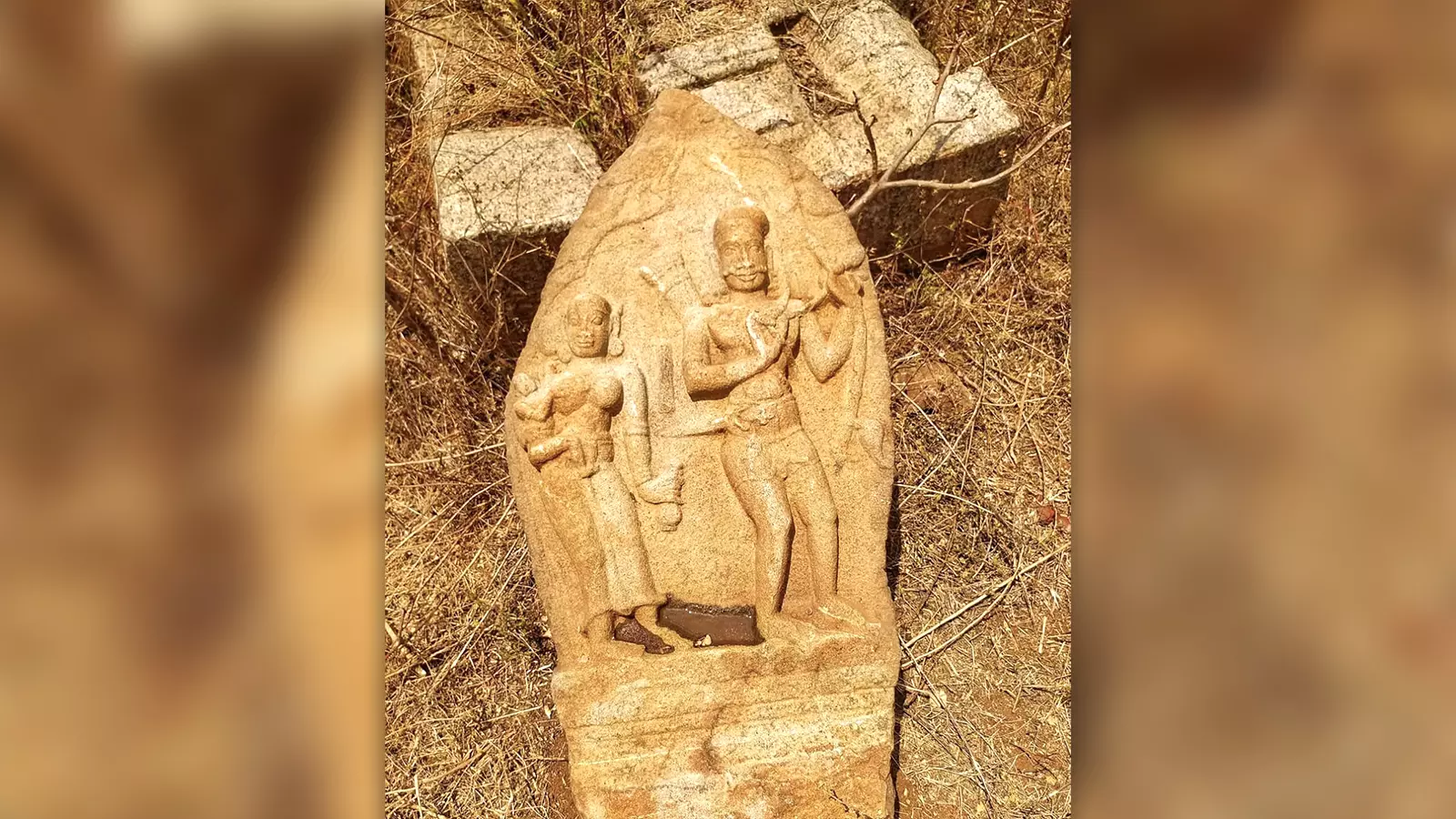

A heroine stone, showing a woman and child, which is worshipped. Villagers of Madurai's Yanaimalai worship this structure as Andal. Experts, on the other hand, claim this structure was erected for a woman who died along with the child.

Stones with female engraving spread across Tamil Nadu, depicting sacrifice of life in acts of bravery, or due to the social milieu were, unfortunately, not even documented. Such structures are not accounted as archaeological materials if they are being worshipped in temples as idols.

When Devi received an award from the Tamil Heritage Trust in September 2023 for her documentation of a new variety of hero stones in Tamil Nadu, her talk at the event enthused many to look for archaeological findings from the women’s eye. The demand for naming women structures as ‘heroine stones’ by Devi was heard loud. Its echoes are now translating into tangible results. The term ‘heroine stones’ introduced by Devi has not only added importance to women, but also added a new perspective to history.

Hero versus heroine

In pastoral societies, livestock were treated like assets. When one pastoral community stole the ‘assets’ of another, the person who brought back the herd or died during the fight, was considered a hero. His act of bravery was recognised by erecting a stone sculpture depicting his act. In later periods, men who were killed in wars were also honoured with hero stone structures. And any warrior who sacrificed his life for the sake of the king or to save the community from calamity was also recognised and worshipped as a hero.

If they died during war or while defending their animals against raids by other pastoral communities, they were honoured by literally being ‘etched in stone’. Such structures were found in abundance across south India and well documented. While in recent years ‘heroine stones’ too have surfaced, it has emerged that there is very little to no documentation on them.

These women are ‘found’ in fanciful clothes, with some carrying weapons and some in acts of sacrifice. A few are also seen carrying their children, or in a state of worship. Unfortunately, many are found neglected in open spaces in ruins.

Tamil literary texts such as Tholkapiyam has references to the lifestyle of Tamil people who lived during 2nd century and the stone structures. Many archaeologists too have recorded that detailed accounts of how and why hero stones were laid are explained in Tholkapiyam, confirming the antiquity of hero stones, but no such reference to heroine stones is found.

Archaeologists, however, confirm that both hero and heroine stones date back to the 2nd century, and studies show the practice existed till the 17th century.

Recognising the archaeological importance of the structures, an exclusive museum for hero stones was set up by the Tamil Nadu government in Dharmapuri district, over 300 kilometres from Chennai, with over 30 hero stones, but none related to women of the time.

With Devi drawing attention to the mismatch, many are now vowing support to efforts to accord due importance to heroine stones.

An engraving showing women going to war. Photo: Devi

“Some hero stones are sculpted along with consorts. But separate women structures are very rare. Few identified by experts are being worshipped by people. We have plans to bring neglected women structures and place them in the museum,” confirmed T Subramaniam, archaeological adviser to the government of Tamil Nadu.

Recarving history through heroine stones

Recently, a women’s stone structure depicting a scene where women are marching to the war field was discovered by archaeology enthusiasts in Krishnagiri district.

“The women’s stone structure portrays a group of five women going to war. They are riding horses with weapons and their pose shows they were heading to warfare. One of them looks like a queen wearing a crown and two other women look like her helpers. They are decked up with jewellery and armed with weapons,” said Aram Krishnan, who along with his team members of Krishnagiri District History Search Organisation, had identified the structure.

Archaeologists had also found hero stone rock structures that act as an evidence for the practice called ‘Navakandam’.

Navakandam involves a person cutting his body parts into nine pieces or a person who sacrifices one of the nine parts of his body for the sake of his vow or a promise he made to the community. Severing one’s own head at one go was considered the supreme sacrifice. Even among these structures, woman performing ‘Navakandam’ was not easily found. But one such structure was recorded in Ulageshwarar temple in Erode district.

Blogger Veludharan was spellbound when he found the stone engraving of a woman performing Navakandam in a temple five months ago. “The hairbun and the breasts of the lady are seen in the structure. There are no inscriptions to give details about reasons for the sacrifice. But it was very rare for a woman to perform Navakandam. This structure should be protected and visitors should be made aware of its importance,” he said.

Women of choices

According to Devi, the engraved stones are evidence of women exercising choices over their lives.

For example, in Madurai’s Chinna Ilanthikulam village, she found a 2.5-feet female stone which was worshiped for many years during the harvest season.

“There is a man and a woman engraving on it. The woman is seen wearing many ornaments. Usually, women were seen as consorts or found in a separate stone structure to represent the women who killed themselves after the death of their husband. But in this structure, the woman is seen along with her partner in a fanciful manner. Her saree is very elegant and elaborate. The sculptural indications of the structure state that it would belong to 16th century. While the man is carrying a spear, the woman had a conch. The woman probably was also part of the guarding job along with her partner,” said Devi.

Another structure found by Devi has now been placed in a local temple. Anandamoorthy, priest of the temple, said the thus-far neglected structure has suddenly gained attention. “The Nagar temple has existed for about 90 years. Two stone structures identified by Devi in grazing land were accommodated at the entrance of the temple recently. We were glad to know that people lived in our region several centuries ago during the Vijayanagara period. We are proud that we have made space for these structures in our temple to help the current generation understand and appreciate the historical importance of our village,” he told The Federal.

The Uthangudi Temple which houses hero stones.

Senior archaeologist Krishnamurthy has penned two books on hero stones of South India with a field experience ranging over some 30 years with the Department of Archaeology of Tamil Nadu. “The worshipping of hero stones faded as Saivism and Vaishnavism became popular religions in the 8th to 13th century period,” he said.

“Many hero stone structures were remnants of a pastoral community. When we get to find women structures, those should be considered as protected monuments. These women’s stone structures provide clues for us to rewrite history. Findings of women’s structure give a new twist to the stories related to living conditions of women in ancient times,” said Krishnamurthy.

Social scientist and acclaimed Tamil writer A.Sivasubramanian has an explanation for why heroine structures are rare.

“Hero stones were erected to inform the society about the bravery of men in battle or warzone. Most women were not part of wars or cattle raids. Moreover, the death of women was not considered as significant as the death of men. The number of structures erected for men is very high compared to structures raised in the memory women. Since some rare structures are now being found, its high time that those are protected and further research and documentation are conducted,” he said.

He also added that though there not many rock structures related to women have been found, many women village deities are worshipped without any structures.

“Couple of women structures which are found now are exceptions. We could spot many small temples in villages where the name of the deity would be a female name but there would not be any sculpted structure. The stories related to sacrifices of the women could be drawn from folk songs,” he said.

A woman, carrying a child, along with her partner. The stone structure was documented by sculpture expert Devi in Maravappati in Madurai.

Renowned archaeologist K Rajan said since heroine stones were very rarely identified and the name of those structures be mentioned as heroine stones.

“Any person who had sacrificed himself for a social cause was glorified as a hero and the community celebrated his sacrifice by laying the memorial stone. This practice was in place to inspire men to sacrifice their lives for the welfare of the community. In modern days, men in the army are recognised with medals and in case of their death, their family is honoured with awards or medals. Death is glorified and the loss of life in the name of patriotism is respected in the society. Whereas in case of women, their sacrifice after the death of husband or male members of the family were not glorified. Separate stones laid for women who committed suicide after the death of her husband were known as ‘sati stones’. In course of time, those women were worshipped as village deities. But separate structures were very rarely laid for women,” said Rajan.