- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How political graffiti is being wiped out from the walls in Bengal

Forward Bloc candidate from Barasat Sanjib Chatterjee is facing a peculiar problem.In the Rajarhat area of his constituency, he is not finding a suitable person to draw the party’s symbol, an open-mouthed lion with flowing mane. “It needs an expert artist to draw a lion on a wall with paint and brush. These days, not many are associated with the profession, so we are not finding...

Forward Bloc candidate from Barasat Sanjib Chatterjee is facing a peculiar problem.

In the Rajarhat area of his constituency, he is not finding a suitable person to draw the party’s symbol, an open-mouthed lion with flowing mane.

“It needs an expert artist to draw a lion on a wall with paint and brush. These days, not many are associated with the profession, so we are not finding any suitable artist to draw the symbol,” said local party functionary Parimal Mistri.

The dilemma the Forward Bloc is facing is indicative of the slow death the art form is facing in West Bengal, the cradle of political graffiti in India.

“The mode of campaigning is changing now. Wall writings are being replaced with memes, digital posters, reels and videos circulated on social media. Gone are the days when parallel competitions used to be waged on the walls of the cities and towns,” said Somnath Choudhury, a veteran graffiti artist from South Kolkata.

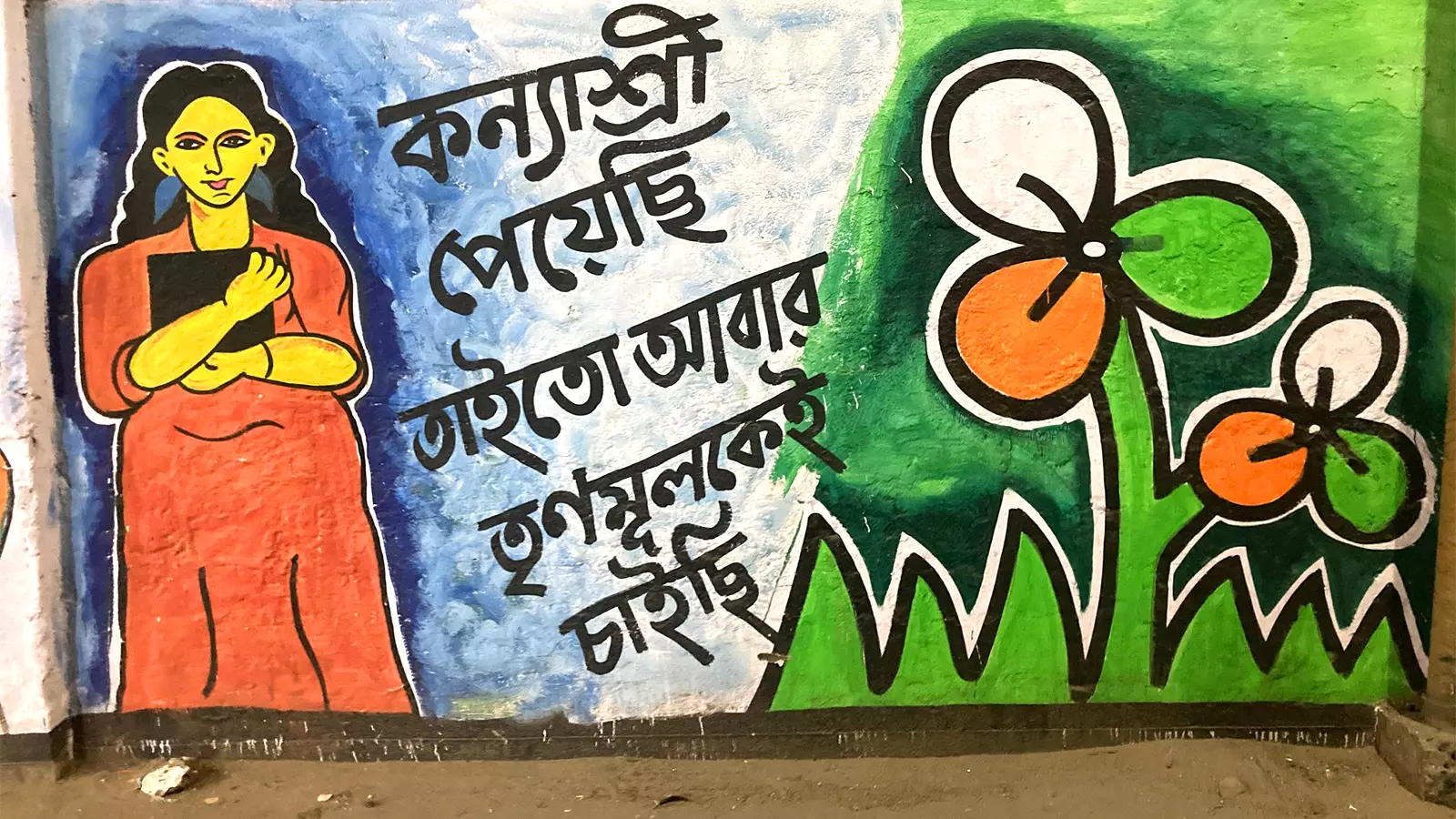

A TMC wall drawing saying, This BJP not again. Photo: Jaynta Shaw

Not too long ago, creative art works ranging from witty political slogans to caricatures of political leaders, adorned the walls, giving some comic relief from violence and intimidation—another integral part of Bengal politics.

“Not that writings on the walls were benign. They were sharp and scathing. But venting once fury through articulation on the walls is much better than hurling crude bombs at political opponents,” said Khokon Mardi, a social activist and graffiti artist from Birbhum.

Political parties have taken to wall writings since the first general elections in the country post-independence in 1952.

Those days printing banners and posters was expensive so candidates opted for wall writings, said Mritunjoy Ghosh, an octogenarian retired teacher from Bankura.

Political wall-writing required training in style, calligraphy, design and utilisation of space, over and above emotional involvement.

During the violent Naxal movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s, wall writings became a popular medium to convey messages clandestinely.

Slogans like ‘Chin-er Chairman amader Chairman (China’s chairman is our chairman)’ and ‘Bonduker nol-i khomotar utso (Power flows from the barrel of a gun)’ flooded the walls.

Naxalites would reportedly write slogans on the walls of crematoriums with charcoal from the pyres of slain comrades as a sign of defiance and tribute.

“By the 1960s, it [political wall writing] had been turned into a sharp instrument of political critique by the Naxalbari movement, a mode soon adopted by the mainstream political parties,” writes Swati Chattopadhyay in the book The Routledge Companion to Art and Politics.

Thus, graffiti emerged as an important form of mass communication with parties using walls as a canvas to take potshots at their rivals with interesting cartoons and couplets.

A TMC poster saying, Got Kanyasree, so TMC again. Photo: Jaynta Shaw

“Humour was a tool of critique as well as self-reflexivity. The tongue-in-cheek playfulness and rhyming made them easy to be cited and recited,” Chattopadhyay adds.

Now, this space is taken by virtual walls on social media forcing graffiti artists to switch over to other professions as the craft is no longer in great demand, Choudhury mused.

Apart from the social media shift, the strict guidelines imposed by the Election Commission on wall writings is responsible for the slow death of political graffitis, he pointed out.

The Election Commission has made it mandatory to take permission of the owner to draw graffiti on the walls of any house or boundary. Most homeowners naturally do not let political parties deface their walls with political slogans.

As the craft is gradually losing importance, political graffiti is losing its sting as well as vivacity of the past.

A few wall writings that are still seen mostly carry symbols of political parties and the names of the candidates.

For humours, jibes and catchy slogans the go to place these days is social media.

“Negotiating with owners to get the wall is a tricky business. Moreover, slogans and couplets on the walls are often covered by the rivals with black paints. That way virtual walls are much more hassle-free and have wider reach, dynamics and audio-visual impacts,” pointed out Trinamool Congress leader Mukul Bairagya.

Going with the digital trend, political parties generously use social media platforms to post parody videos, reels, news clips, posters, cartoons and slogans.

The CPI(M)-led Left Front of which the Forward Block is a constituent recently released an animated video lampooning TMC and Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee on corruption.

The video also suggested a tacit understanding between the TMC and the BJP.

Tune of a popular number “Jamal kudu” has been used in the video for an instant connect with the voters.

The Left Front, which once dominated the craft of wall writings, is marching ahead of its rivals even in virtual platforms.

The CPI(M) in West Bengal unveiled an artificial-intelligence driven anchor named Samata to campaign for the party on social media.

Not to be outwitted, the ruling TMC came out with an animated video series called Jumla Baba, targeting Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s alleged unfulfilled promises.

In the first video of the series released on April 1, the theme is mainly inflation, unemployment and freeze on central funds. The characters in the video resemble BJP leaders Narendra Modi, Amit Shah, Yogi Adityanath, Suvendu Adhikari and Dilip Ghosh.

The second video primarily depicts alleged misuse of central agencies such as the Enforcement Directorate and the Central Bureau of Investigation.

The third video released on April 23 highlights closures of tea gardens allegedly due to Centre’s apathy.

Apart from official handles, parties are overtly and covertly utilising the services of their supporters and functionaries to campaigning on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram to attract voters, taking advantage of the high internet penetration in the country.

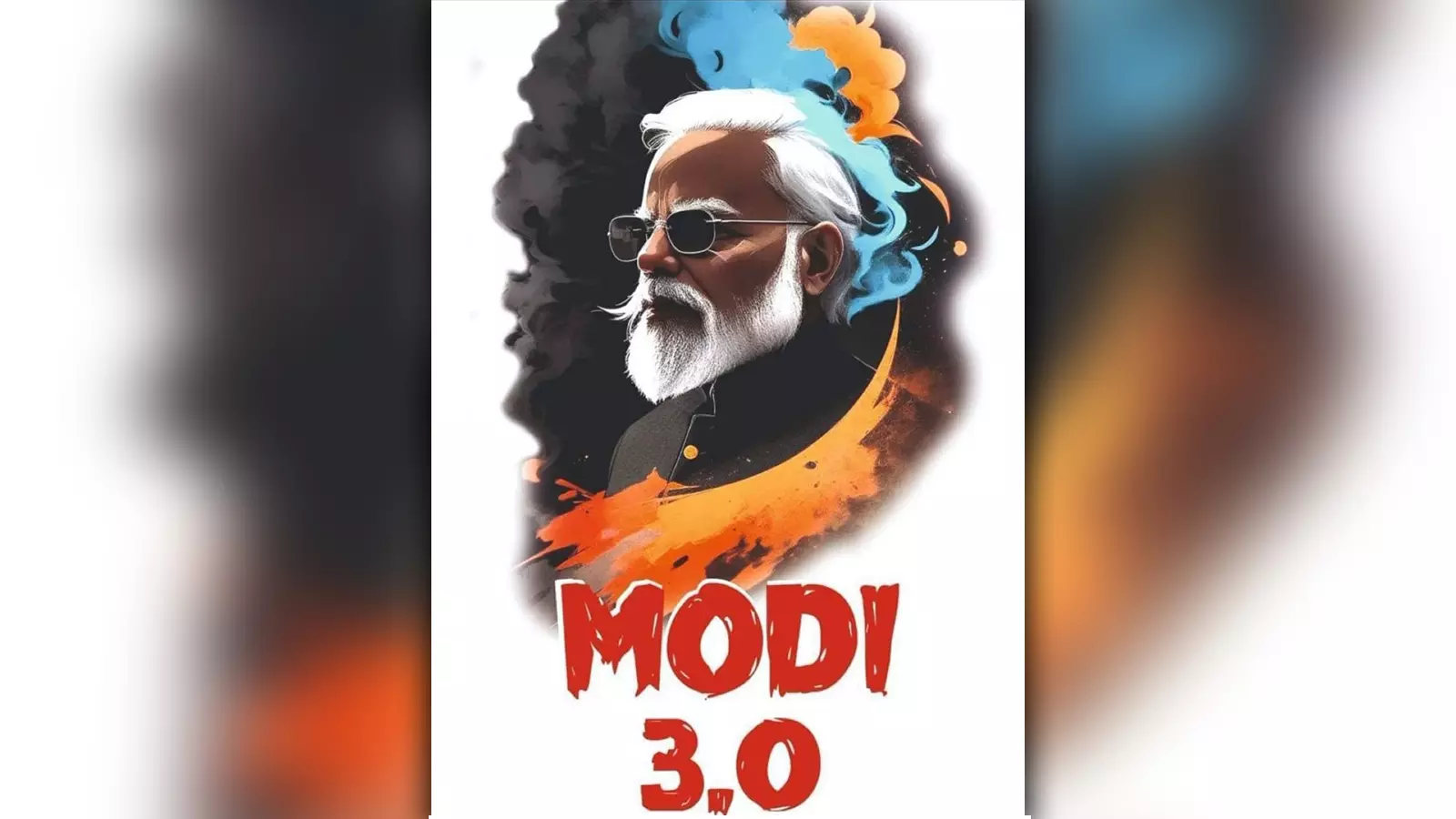

A BJP poster claiming a third term.

Social media advertisements have become another popular mode of campaigning. The BJP is a dominant player in this domain.

“Analysis of this data revealed that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has spent the most on political advertisements, but the expenditure on advertisements by BJP’s proxy pages exceeded that on their official advertisements,” the Alt News recently reported.

The advertisements are posted directly on official party pages and also on pages that support a particular political outfit. The expenditure on advertisements or endorsements on supporters’ pages are not accounted for by the ECI. Some of these unaccounted-for pages are MemeXpress, Political X-ray, Ulta Chasma, Nirmamata, The nation vives, Paltu-paltan, Amar Sonar Bangla. These pages regularly post party publicity content and their own content designed for the party they back.

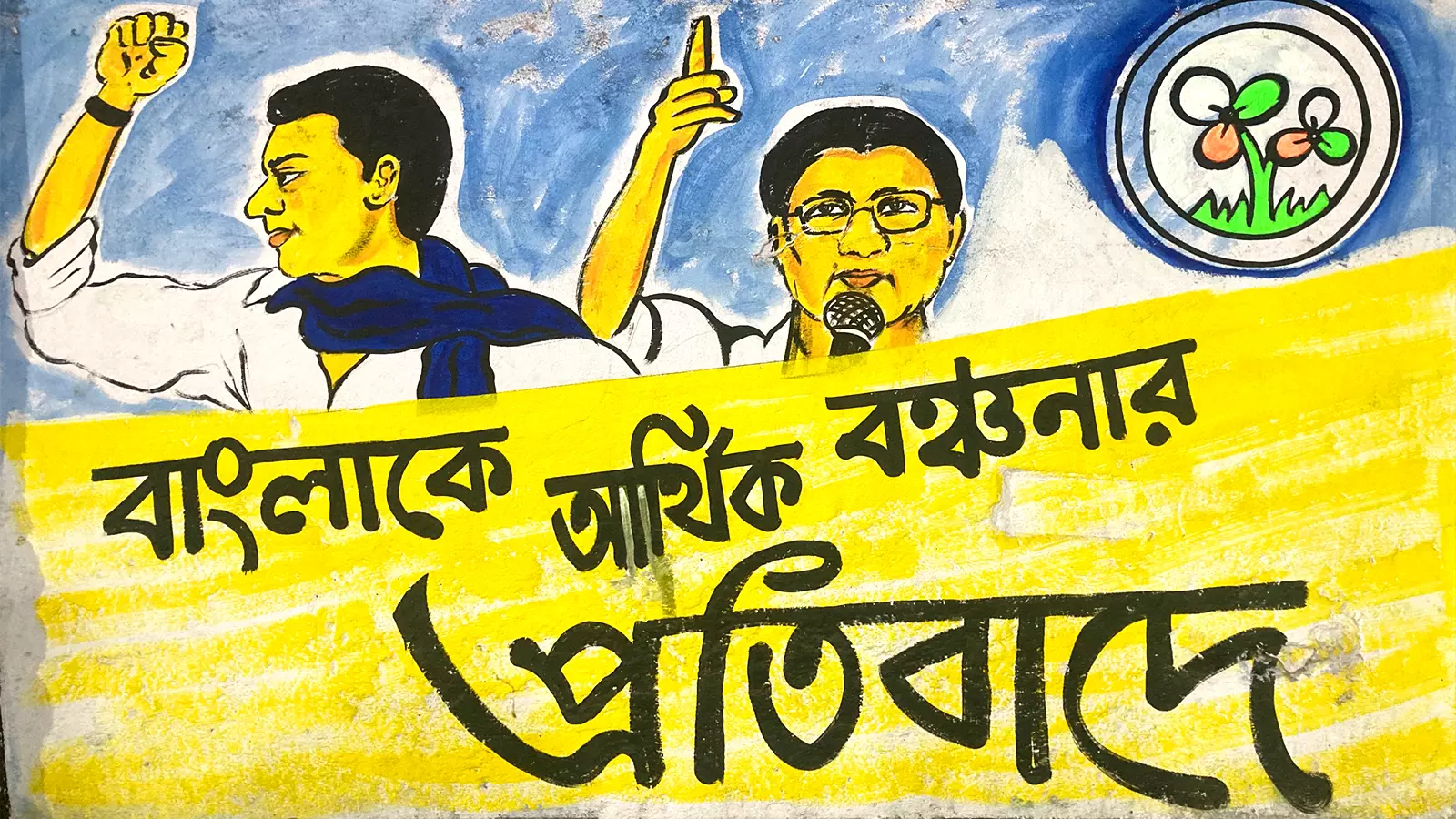

A TMC poster declaring, Fighting economic discrimination against Bengal. Photo: Jaynta Shaw

Since such pages are unregulated, they are also a source of paddling fake narratives, acting as propaganda spreading channels.

While the medium of virtual campaigning is getting more and more traction, the few graffiti that are still visible on the walls this election could be the last of the genre.