- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Barring a few Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) staffers beating the scorching summer heat under its shed, the mausoleum where rests Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha, is desolate.The reposeful ambience of the mausoleum in Murshidabad’s Khoshbagh lies neglected today. Photo: Wikimediaabout the Nawab who lies peacefully there in the grave...

Barring a few Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) staffers beating the scorching summer heat under its shed, the mausoleum where rests Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha, is desolate.

The reposeful ambience of the mausoleum in

Murshidabad’s Khoshbagh lies neglected today. Photo: Wikimediaabout the Nawab who lies peacefully there in the grave alongside his relatives and betrayers alike.

In all, there are 34 graves in the sprawling burial place amidst flowers and foliage near the banks of the river Bhagirathi. Along with the mortal remains buried here are the most controversial and decisive moments of Bengal’s history, which has now been dug out to give political twists based on how one interprets the momentous episode.

The attempt to revive the past to contextualise it with the present politics began with the BJP nominating Amrita Roy, a 62-year-old ninth generation descendant of Krishnachandra Roy, from Krishnanagar to take on the Trinamool Congress’ Mahua Moitra.

Murshidabad’s Khoshbagh lies neglected today. Photo: Wikimedia

Roy, reverently referred to as ‘Rajmata’ (the queen mother) by many in Nadia, had no prior political involvement. But she has been in the BJP’s grand scheme of things since 2014 because of her family’s lineage.

The party had then offered her to contest from the same seat, but she had declined because, among others, she had no intention to be compartmentalised by any particular political hue when she and her family is revered by all, she told The Federal.

This time around, after initial hesitation, she took the plunge “considering the overall sense of dismay over the current situation in the state”.

The BJP sources, however, said she was persuaded by the party’s top central leadership to accept the offer.

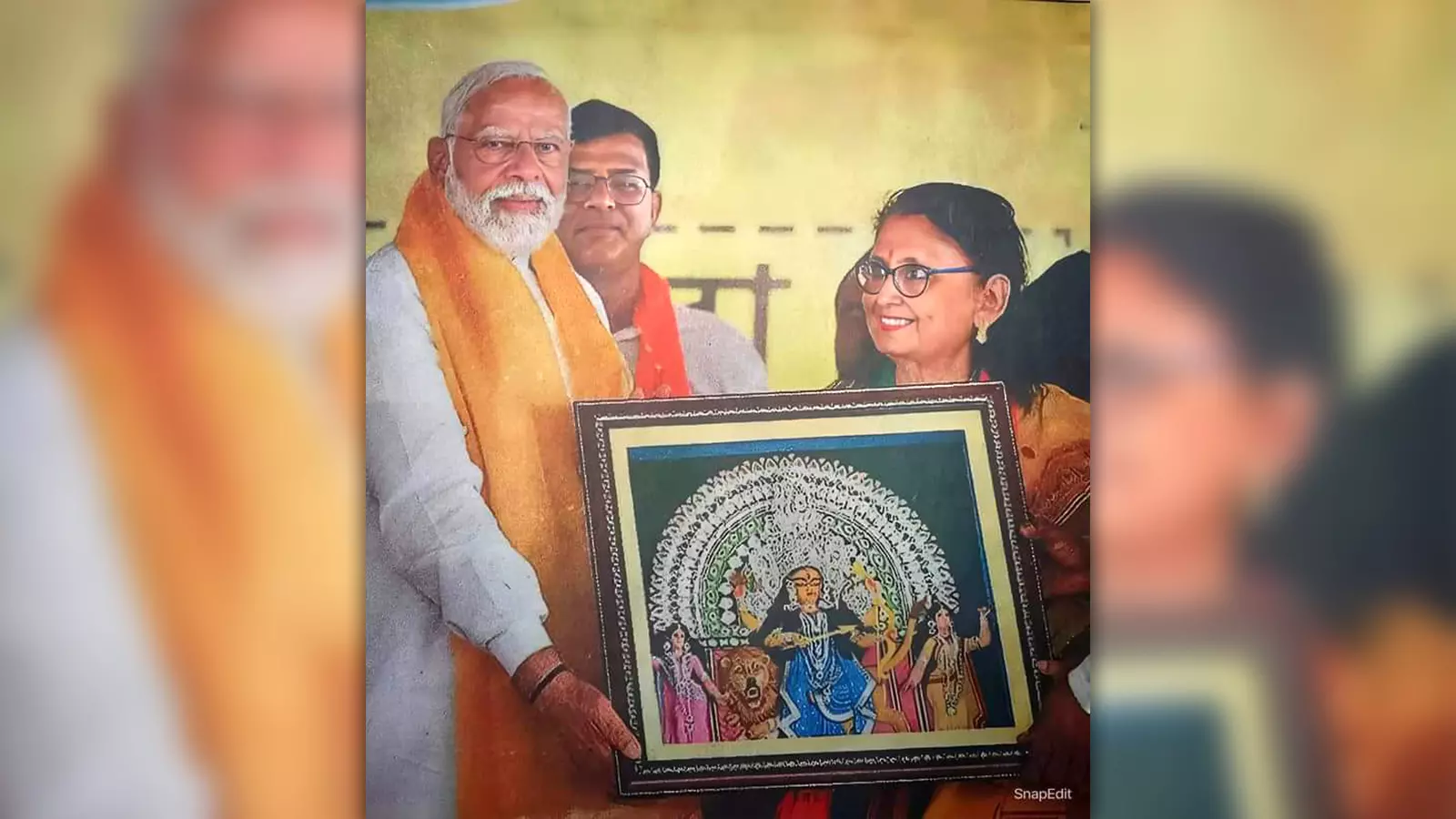

Her importance in the BJP’s strategy to breach the TMC citadel can be gauged from the fact that she was one of the two candidates from Bengal whom Prime Minister Narendra Modi personally called up for pep talks after assigning party tickets. The other being Rekha Patra, a survivor of the alleged sexual violence in Sandeshkhali. The BJP has fielded Patra from Bashirhat to make her a symbol of purported subjugation of women under Mamata Banerjee’s TMC regime.

BJP candidate Amrita Roy is a ninth generation descendant of Krishnachandra Roy.

Roy’s prominence in the election strategy of the BJP stems from her link with Krishnachandra, the erstwhile zamindar of Nadia from 1728-1782, who received the honorific of Maharaja.

A key figure in post-medieval era Bengal, Krishnachandra joined hands with the East India Company and Mir Jafar to defeat Siraj ud-Daulah in the Battle of Plassey that paved the way for British rule in the Indian subcontinent.

Unlike Siraj’s compromised military general Mir Jafar, Krishnachandra, far from being condoned as a traitor, is remembered more for his immense contribution to Bengali literature and culture. He played a key role in popularising Durga Puja and Jagadhatri Puja. For Hindu rights, he conspired against Siraj to protect the Sanatan Dharma, and honour of Hindu women.

The BJP is trying to endorse the narrative by giving political currency to Krishnachandra’s legacy by juxtaposing it with Sandeshkhali.

“Siraj-ud-Daula, the last Muslim Nawab of Bengal, would kidnap beautiful Hindu women, while they came to bathe on the banks of Ganga. During monsoons, the tyrant would sink ferry boats, and watch hundreds of Hindu men, women and children, who didn’t know how to swim, perish in the rising waters, for his entertainment. Mamata Banerjee has ensured the deranged legacy of dehumanising Hindus continues in #Sandeshkhali,” BJP IT Cell head Amit Malviya wrote on his X handle.

“Maharaja Krishnachandra helped the British to save our Sanatan (Hindu) religion, otherwise it would have been destroyed…. Siraj-ud-Daulah was a despot, and his exploitations of Hindu women were well documented,” claimed Amrita Roy sitting at her office room in the grandiose Krishnanagar Palace.

The TMC hit back calling Krishnachandra a stooge of the East India Company, who betrayed the nation.

Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah's dargah in Murshidabad.

The historical context over which the BJP and the TMC are trading barbs has no resonance in Murshidabad, the decaying capital of Nawab, located some 100 kilometres north of Krishnanagar, named after Krishnachandra. Over the years, Murshidabad has grown into an overpopulated impoverished district. According to Niti Aayog’s multidimensional poverty index, 16.55 percent of its population is multi-dimensionally poor.

The commoners such as the three ASI maintenance staffers at the mausoleum, The Federal interacted with, have a far more objective view of the history than the spin doctors of the political outfits.

“Digging them (historical figures like Siraj and others) out of the graves will not change what they did or didn’t, and more importantly it will not have any fruitful bearing on our life,” said Mariya Bibi, an ASI employee, entrusted with the upkeep of the mausoleum.

Seated next was her colleague, Ranjit Das. To him it’s immaterial whether Siraj was a Hindu baiter. “It is his memory that serves food to my family,” he said metaphorically.

Murshidabad was once the capital of undivided Bengal and a global trade centre. In the 18th century it contributed around five per cent to the world’s GDP and the capital was compared with London for its opulence. It has today degenerated into one of the most backward districts in India and a major source of cheap migrant labourers.

Its once famous silk and textile industries, ivory carving, bell-metal industries and clay model making units died a slow death.

Bidi making is the only industry in the district that has survived the storms of change. Out of its over 71 lakh population (as per 2011 census), 17 lakh are engaged in bidi making. But the thriving industry is plagued by poor wages and working conditions.

Mariya Bibi hopes that the political row over Siraj legacy would draw more tourists to the place, creating livelihood avenues for the local residents.

The relics of its glorious past is still a top draw for tourists, and only source of sustenance for many locals. Unfortunately, the tourist season lasts only from November to February because the region is notorious for its hot and sultry summers.

“During tourist season, I could earn Rs 500-600 daily… But now my daily earnings have dipped to around Rs 200,” said Pintu Sheikh (29), an e-rickshaw driver in Murshidabad town.

Even for the tourists, Murshidabad has nothing great to offer other than a modicum of putrefied monuments that stand testimony to administrative apathy it has faced for centuries.

It was founded in 1702 by Murshid Quli Khan, who moved the capital of Bengal from Dhaka (now capital of Bangladesh) to the place subsequently named after him.

As a principality of the Mughals, it soon flourished into a bustling centre of global trade. But its glory and fortune were short-lived.

After defeating Siraj in the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the East India Company shifted focus to its new administrative and business headquarters in Calcutta (now Kolkata). The earthquake of 1897 and change of course by river Bhagirathi too played a part in destroying its once magnificent skyline.

Except for a mosque, hardly any impressive structures from Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula’s time has survived.

Its main tourist attractions Hazarduari Palace and Nizamat Imambara were built by subsequent rulers decades after Siraj’s death and do not have much historic significance.

The Imambara in Murshidabad.

The hundred-odd Nawabi families, who still reside in Murshidabad and its nearby areas, are the descendants of Nawab Mir Jafar and not Siraj.

In his erstwhile kingdom, Siraj has long been pushed into oblivion, invoking neither great adoration nor despise.

“Like most nawabs he (Siraj) had his share of goodness and follies…. Instead of politicising those legacy — good or bad — it will be worthwhile if our leaders devote their time and energy for our today. Or else there will be no future here,” said Syad Gohar Alam Meerza, a 11th generation heir of Mir Jafar.

His family has long buried the hatchet with its controversial past and has moved on. It’s time for the politicians to follow suit.