- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Why extinction of Toda buffaloes spells extinction of Toda language, culture

Twenty-year-old Suchithra Devaraj, a young Toda, cherishes her buffalo as a precious pet.“My grandmother received 25 buffaloes as a gift from her parents at her wedding. My mother received between 10 and 15 buffaloes. I have two sisters, but my father could only afford to give two buffaloes each at their weddings,” Suchithra tells The Federal.The reason is the rapidly declining Toda...

Twenty-year-old Suchithra Devaraj, a young Toda, cherishes her buffalo as a precious pet.

“My grandmother received 25 buffaloes as a gift from her parents at her wedding. My mother received between 10 and 15 buffaloes. I have two sisters, but my father could only afford to give two buffaloes each at their weddings,” Suchithra tells The Federal.

The reason is the rapidly declining Toda buffalo population.

“It is believed that the number of buffaloes a woman brings is indicative of the prosperity that the household will have. According to Toda cultural beliefs, as the buffalo herd grows, so does the family’s wealth.”

People of the Toda tribe, a Dravidian ethnic group who live along the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu, worship buffaloes both during auspicious festivals and deaths alike, emphasizing their importance. “They sing buffalo songs in temples and light temple lamps with buffalo oil. A home without a buffalo is considered inauspicious,” says Suchithra.

The Toda breed is known after its herdsmen and thrives well in high rainfall and high humid area. The buffaloes are found to produce moderate quantity of milk under an extensive management system with daily milk yield ranging from two to six litres.

But the Toda buffalo, the only indigenous buffalo breed of Tamil Nadu, is facing extinction.

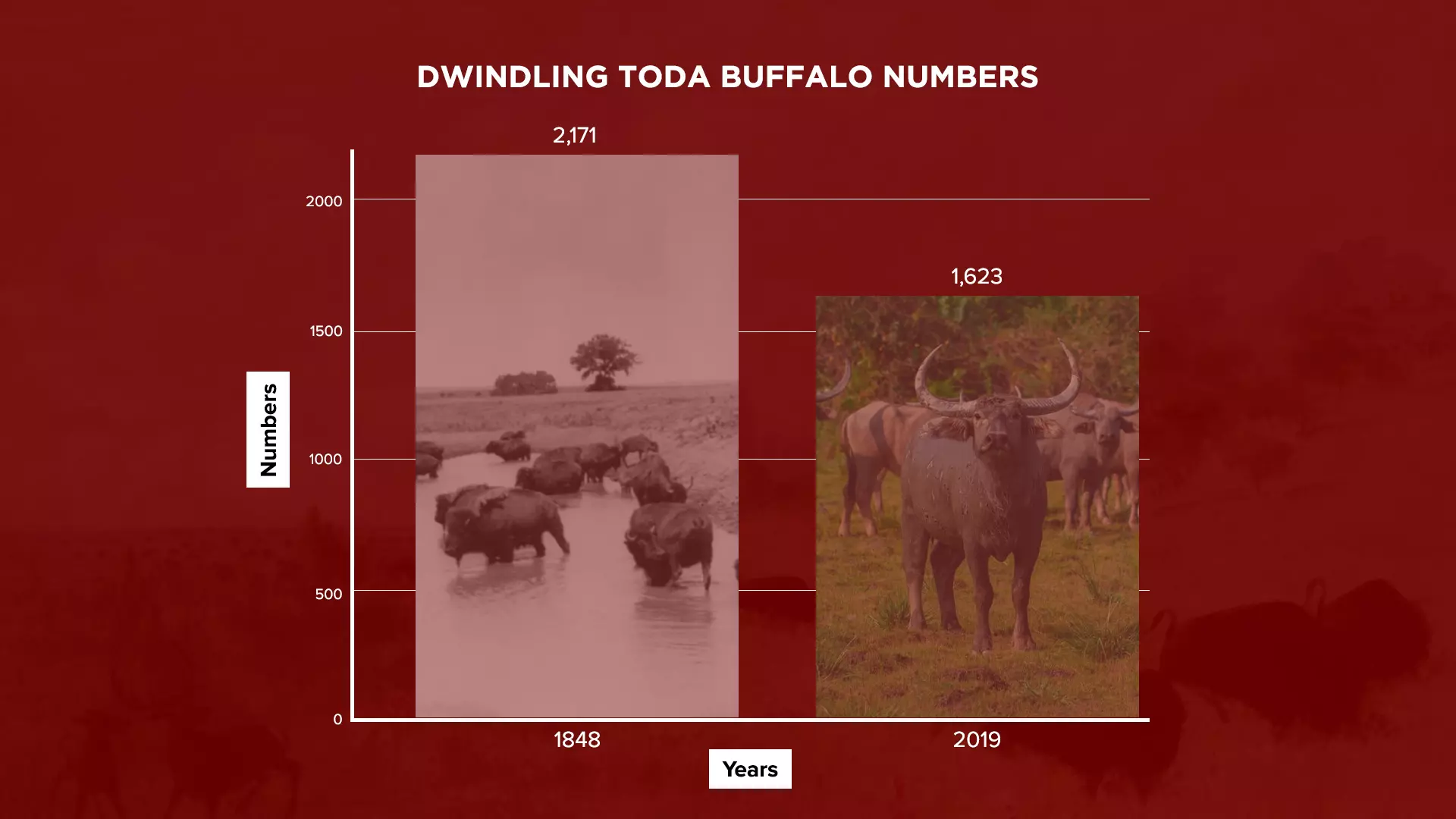

According to the National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, records indicate a decline in the Toda buffalo population from 2,171 in 1848 to just 1,623 in 2019, with no significant improvement over the years.

Experts attribute the dwindling population of Toda buffaloes to habitat loss, invasion of exotic grasslands, and a shift among tribes from pastoral lifestyles to other occupations. The buffalo has been classified as an endangered species since its numbers began to decline since early 1990s.

Toda’s cultural connection with buffaloes

The existence of Toda buffaloes, a genetically isolated species, could be traced back to the earliest reference of Finicio (1603) who wrote of the tribe: “They have no crops of any kind, and no occupation but the breeding of buffaloes, on whose milk and butter they live”.

Experts attribute the dwindling population of Toda buffaloes to habitat loss, invasion of exotic grasslands, and a shift among tribes from pastoral lifestyles to other occupations. Photos: Pramila Krishnan

Toda tribal rights activist and language expert K Vasamalli, in a conversation with The Federal, highlighted that the decline in buffalo numbers has led to the loss of many words related to buffaloes in the tribal language and also spoke about why she thinks government’s conservation efforts won’t generate desired results.

While with Tribal leaders stressing the urgent need to protect the buffalo breed, a scientific project aimed at conserving the breed has been initiated, many are not happy. While the Indian government pursues cryogenic preservation, Toda tribes advocate financial support to conserve the animal in its natural environment.

“Each buffalo in the family is given a name, and different sizes of buffalo herds also have distinct names. As buffaloes have been disappearing, so have our words. Several words connected with grazing and types of grass are now lost. While we appreciate the government's scientific efforts to protect the buffalo breed, conservation in their natural habitat is crucial for our community. Our grasslands have shrunk significantly, and many buffaloes fall prey to wild animal attacks when grazing in forested areas. Amusement parks have encroached our grazing lands, leaving our buffaloes without adequate food. The Nilgiri Hills have now become a tourist destination,” says Vasamalli.

“People of the Toda community have been organising special prayers as the dwindling population is seen as a bad omen by tribal elders,” she said.

Vasamalli notes that the Toda buffalo was first recognised as a threatened species by the Food and Agriculture Organization in 1990 and was listed as endangered in 2000. However, it wasn't until 2007 that the Indian government officially categorised the Toda buffalo as endangered in the national breed registry.

"For a long time, the Toda buffalo breed has been at the risk of extinction. The total population hasn't even reached 2,000. Relying on cryogenic scientific preservation suggests there is little hope left to save our identity-defining animal. It's high-time the Indian government promotes buffalo breeding in the community," she adds.

Science and social needs for Toda buffalo

When The Federal approached officials from the Tamil Nadu Animal Husbandry Department to identify the primary reasons for the decline in buffalo numbers, veterinarian and head of the cattle research station in Nilgiris, N Prema, explained that infertility among Toda buffaloes has led many young Toda men to seek other, more financially rewarding occupations instead.

A Toda dairy temple. All the signs and symbols on the structure are related to buffaloes.

"If grassland areas diminish, buffaloes won't get the nutritious food they need for breeding. Only healthy buffaloes can reproduce. A mother buffalo needs nutrition for the fetus’s development and the calf's healthy birth. The decline in grasslands has significantly reduced buffalo fertility rates. According to available statistics, buffalo fertility rates have dropped to about 50 per cent. We are currently training Toda youths and entrepreneurs on providing nutritious food and basic first aid for buffaloes,” says Prema.

Karthikeya Sivasenapathy, Managing Trustee of the Senaapathy Kangayam Cattle Research Foundation, argues that addressing infertility and promoting natural conservation are effective solutions to save Toda buffaloes. He asserts that the success rate of reviving animal species through scientific preservation is much lower than through in-situ conservation.

"Since buffaloes are deeply intertwined with Toda culture and essential for their rituals, the government should promote conservation in collaboration with the community. Scientific conservation of embryos and semen in controlled environments may not ensure the animals survival during pandemics like COVID-19. Moreover, the costs associated with scientific preservation are higher than those for natural conservation with community involvement,” he said.

He emphasized that India, home to more buffalo breeds compared to other countries, would receive global recognition for serious efforts to conserve the Toda buffalo.

Disease resistance remains a hurdle

When asked about Sivasenapathy's arguments, a senior professor from Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University explains ongoing programs for buffalo conservation.

"As part of scientific preservation, embryos and semen from buffaloes have been collected and cryogenically frozen. We have collected 56 embryos and 2,700 doses of semen so far. While it's true that preserving embryos and semen is costlier than conserving them in their natural habitat, the scientific project was conceived as a last resort for future revitalization. In collaboration with the Indian Council for Agricultural Research (ICAR), the government research station has raised and returned 14 male calves to Toda tribes for natural conservation," he said on condition of anonymity.

He acknowledges that animals revived through scientific conservation may have lower survival rates and lack disease resistance compared to live Toda buffaloes adapted to severe climates and pandemics.