- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

“We were flying a C-47 aircraft with no engine super changers for high-altitude flying, with an 18,000ft ceiling limit. We should have been flying a B model for this kind of work with higher mountains going over 20,000 ft with air pressure and available oxygen at that point much less than 50 per cent of normal heights. But you just do what you have to do, so we carefully threaded our...

“We were flying a C-47 aircraft with no engine super changers for high-altitude flying, with an 18,000ft ceiling limit. We should have been flying a B model for this kind of work with higher mountains going over 20,000 ft with air pressure and available oxygen at that point much less than 50 per cent of normal heights. But you just do what you have to do, so we carefully threaded our way through and landed in our new—but temporary home in China.”

Read the testimonial of a 22-year-old 2nd lieutenant of the US army who took part in the crucial supply operation at the China-Burma-India theatre during World War II.

The experience might sound terrifying, but it did not give away the extent of danger they actually encountered flying over Himalayas in the forward areas of northeastern India.

“A four-degree drop in temperature per one thousand feet of altitude, it was freezing out there. Dressed for the tropics, and with an inadequate heating system in the plane it was unpleasant,” the young pilot wrote in his diary.

More than the adverse temperature and ill-equipped technology, it was the treacherous route that was proving to be a bigger challenge.

The 500-mile aerial route—through Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Tibet, Myanmar and Yunnan (China)—was the most hazardous flying area in the world at that time. Even today pilots dread flying over it.

About five years ago in June 2019, a transport aircraft of the Indian Air Force went missing after taking off from Jorhat airbase for the forward landing ground at Mechuka along India-China border in Arunachal Pradesh. The crew of the ill-fated plane reportedly met with the same old adversity that the allied forces encountered during the war while flying over the route—the sudden downdraft.

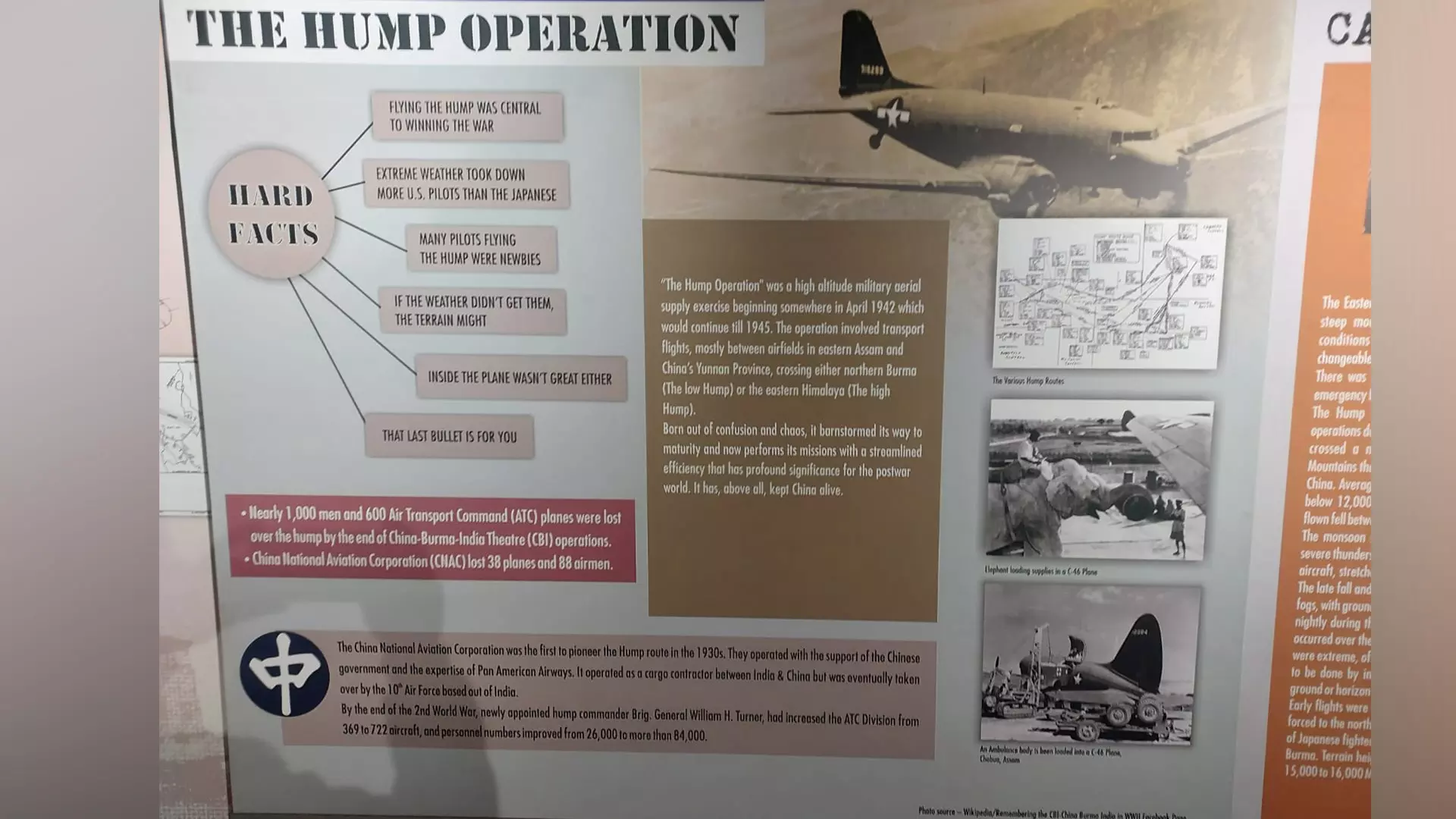

Some 650 American transport planes crashed negotiating extreme weather conditions and difficult terrains in the area, killing more than 1,600 airmen during the World War II military operations between April 1942 and August 1945.

The 42-month-long campaign was launched by the allied forces in response to the Japanese army’s siege to the vital Old Burma Road, a 1,150 kilometres mountainous highway connecting Lashio in Burma (now Myanmar) and Kunming in China.

The blockade of the lone overland path cut the supply line for the Chinese army under the command of General Issimo Chiang kai shek.

“Ensuring uninterrupted supplies for the Chinese army was seriously critical to winning the war,” according to an American military document.

In the wake of Japan’s massive land, sea, and air offensive in the Far East and its attack on Pearl Harbor, the allied forces felt the need to tie down Japan in a war with China.

What ensued was one of the largest ever airlifts in aviation history transporting nearly 6.5 lakh tonnes of supplies, including fuel, rations and ammunition to the Chinese troops. The operation proved to be extremely dangerous as was evident from the number of deaths and the loss of aircraft.

American journalist and historian Theodore Harold White, reporting from China during the war, described the operation thus: “The most dangerous, terrifying, barbarous aerial transport run in the world.”

White wasn’t exaggerating. It was the almost suicidal mission the US-led allied forces undertook to pin down the Japanese. What made the route so dangerous was the sudden elevation needed to negotiate the Himalayan mountains in Arunachal Pradesh from the plains of Assam before diving down to the base in China.

For the sudden climb and the drop the route offered with deep gorges and mountains rising beyond 10,000 feet, it was nicknamed “hump” by those who had undertaken the journey.

“The Brahmaputra valley floor lies 90 feet above sea level at Chabua, a spot near Dinjan where the principal American valley base was constructed. From this level, the mountain wall surrounding the valley rises quickly to 10,000 feet and higher.

“Flying eastward out of the valley, the pilots first topped the Patkai Range, then passed over the upper Chindwin River valley, bounded on the east by a 14,000- foot ridge, the Kumon Mountains. They then crossed a series of 14,000-16,000-foot ridges separated by the valleys of the West Irrawaddy, East Irrawaddy, Salween, and Mekong Rivers. The main ‘Hump’, which gave its name to the whole awesome mountainous mass and to the air route which crossed it, was the Santsung Range, often 15,000 feet high, between the Salween and Mekong rivers,” described an Air Force record.

“The foothills of Himalayas rise more than 15,000 (feet) from the upper Assam plains in a mere short distance of few kilometres touching Arunachal Pradesh, which give the pilots a very tight leeway after taking off from upper Assam in manoeuvring their aircraft to a desired height and angle….. winds lifted planes to more than 25,000 feet and then back to 7,000 feet shortly thereafter,” according to Colonel (retired) Satish Singh Lalotra, who had the unique experience of flying over the Hump route during his stint with the Special Frontier Force in early 1990s.

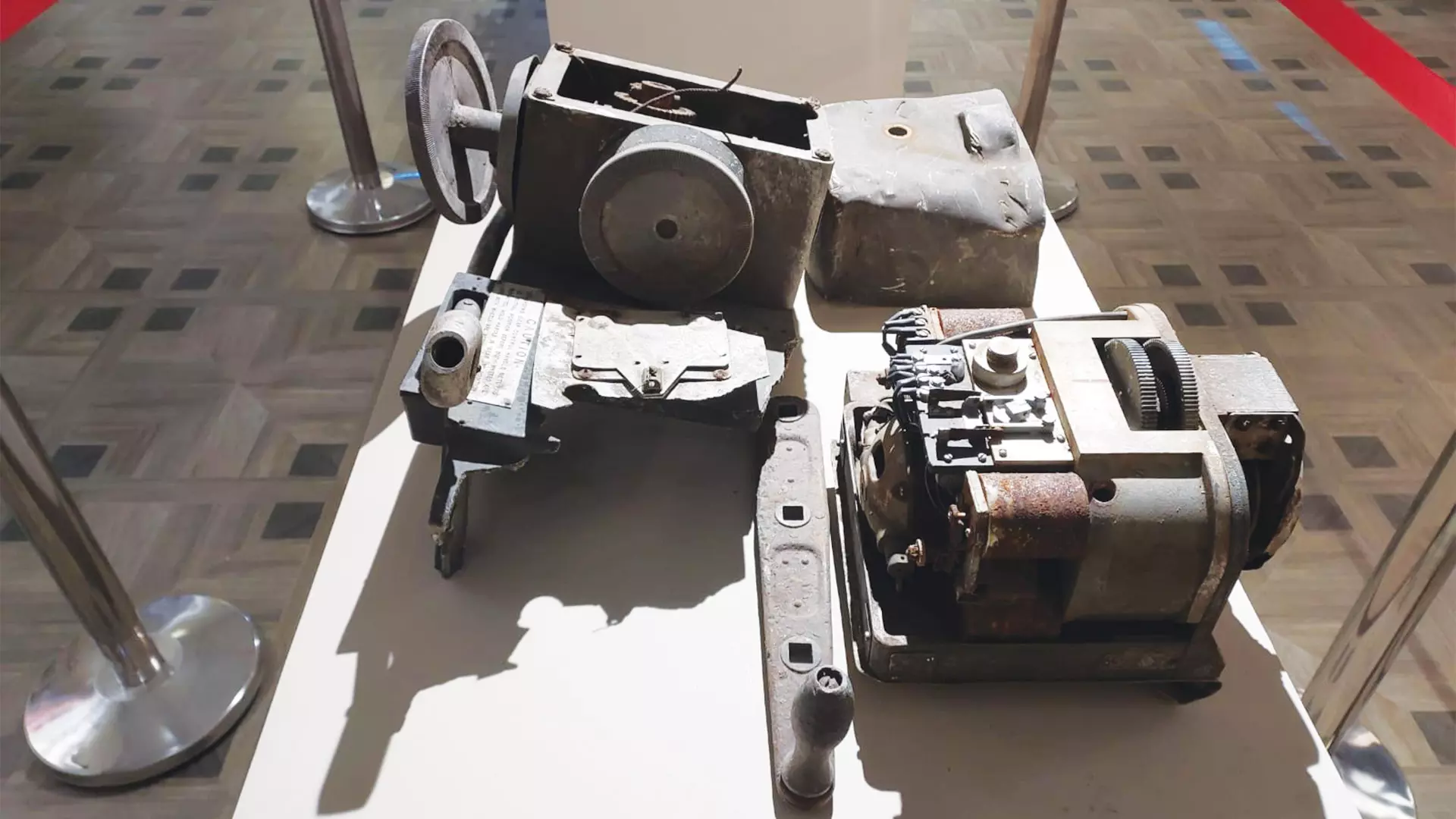

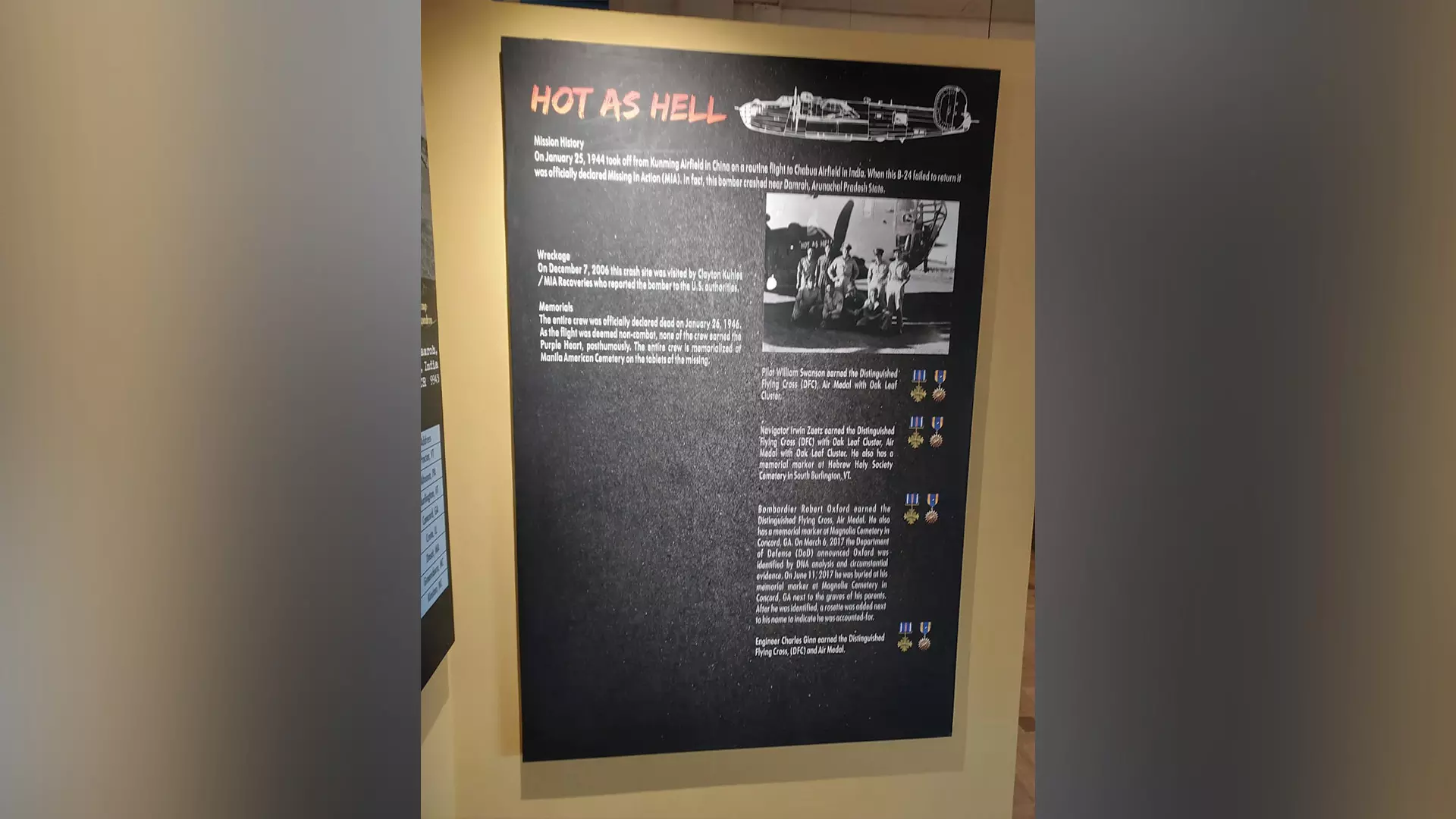

To locate the remains of fallen airmen and aircraft, the US Defense Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Accounting Agency (DPAA) initiated a search operation in the Himalayan mountains of Arunachal Pradesh in 2016-17.

The search led to the recovery of wreckage of aircraft, dresses of slain airmen and soldiers, their diaries, letters and many other items of daily use.

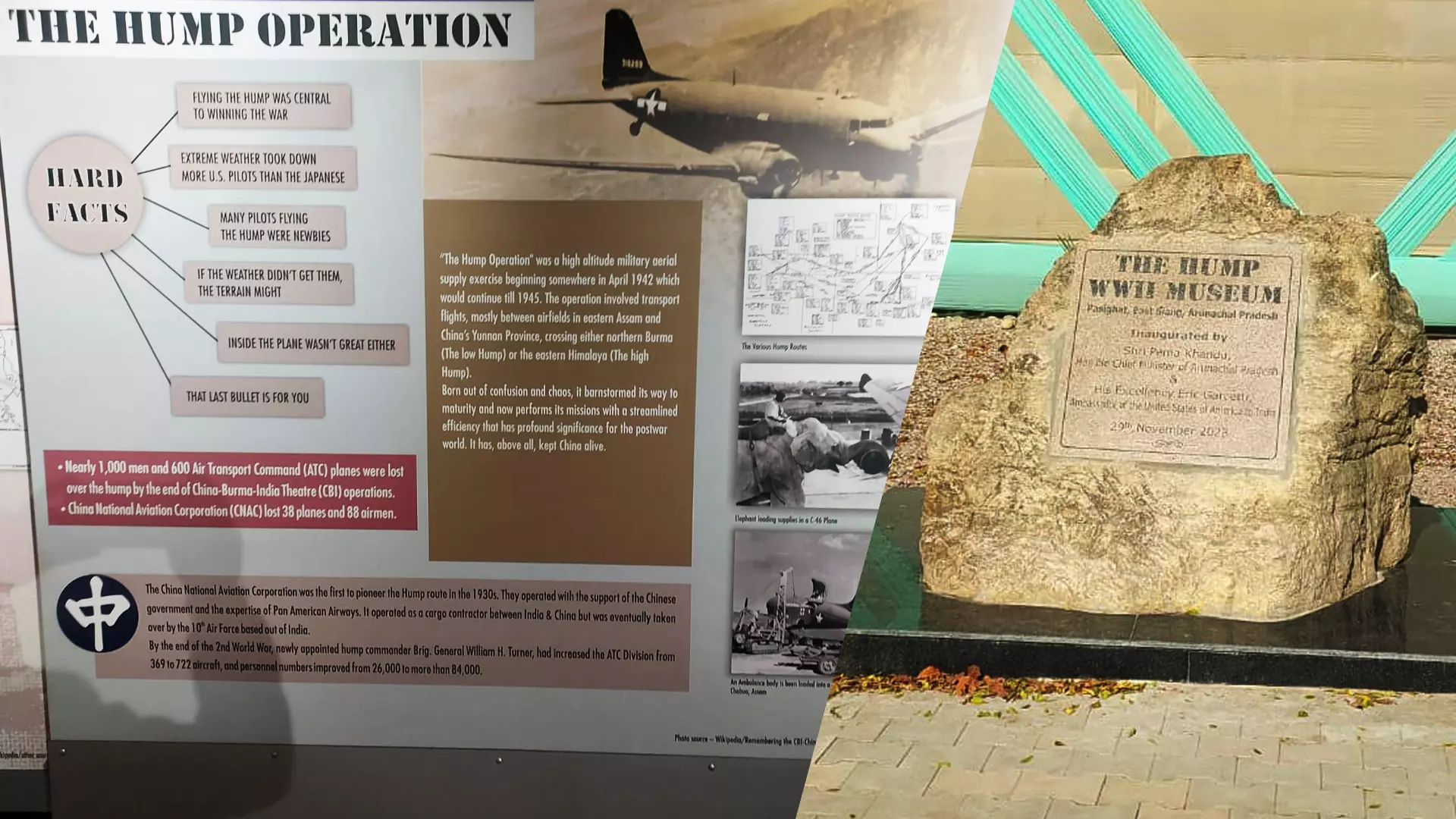

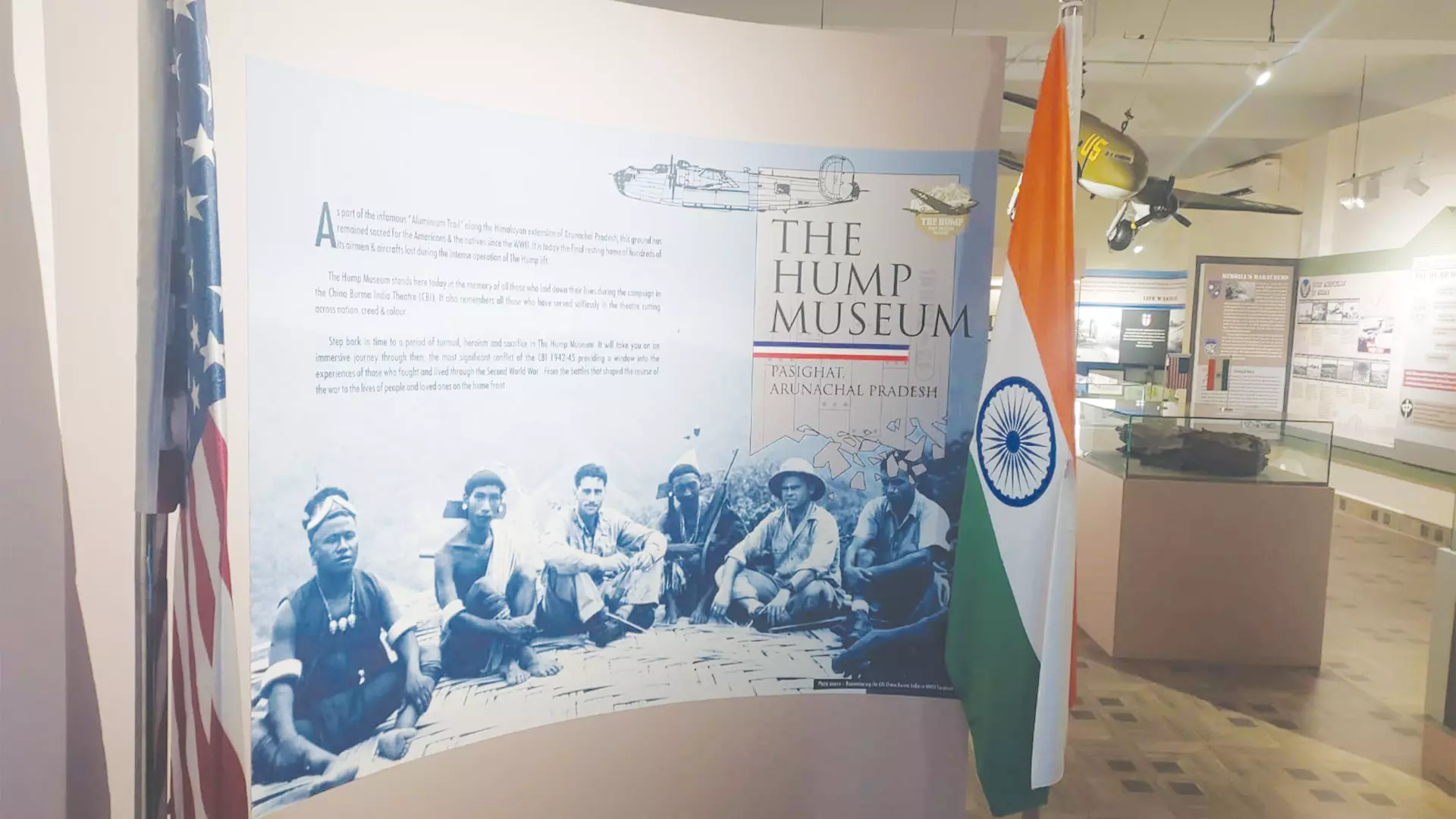

The remains are now exhibited in a museum — The Hump Museum — set up in Pasighat, the East Siang district headquarters of Arunachal Pradesh. It was inaugurated by US Ambassador to India Eric Garcetti and Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu on November 29.

“This museum is a window to the forgotten campaign and a tribute to the fallen airmen of the Allied forces during World War II. This museum is a work in progress because search for more aircraft and mortal remains of those who died during the operation is on,” said Sukumar Tayeng, the caretaker of the museum.

The Arunachal Pradesh government has sought US ambassador’s help to facilitate the exploration of some 30 locations in the state where remnants of WWII aircraft are still believed to exist.