- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

What contemporary Ladakhi art has to say about the region, its people

On August 1, 12,000 feet above sea level, Leh in Ladakh came to life. There was an apparent riot of ideas and colours, focused on culture and community, spread on canvases. With sā in Ladakhi language meaning soil, the art festival, organised in Disko Valley of Leh town, was also a bid to draw attention to the urgent need to ‘save the soil’, implying the ecosystem of Ladakh....

On August 1, 12,000 feet above sea level, Leh in Ladakh came to life. There was an apparent riot of ideas and colours, focused on culture and community, spread on canvases. With sā in Ladakhi language meaning soil, the art festival, organised in Disko Valley of Leh town, was also a bid to draw attention to the urgent need to ‘save the soil’, implying the ecosystem of Ladakh. The highest-altitude-art exhibition was based on the theme of climate, culture and community in high altitude environments.

The month-long exhibition featured a selection of site-specific art installations made using only discarded, renewable or reusable materials. The nearly-month-long event also saw sculptures and other visual arts installed to spread awareness about climate change.

The exhibition was also significant for bringing to light contemporary Ladakhi art and artists. The exhibition featured the works of many local Ladakhi and international artists, among them were renowned young artists like Gurmet Kungyam, Jigmat Angmo and Anayat Ali. They displayed their art land installations depicting ecosystem fragility, sustainability, ecology, and environment.

“Ladakhi art has usually been seen through the prism of traditional form of arts like Thanka paintings, mask-making, murals and other paintings associated with Buddhist monasteries,” Ladakh Arts and Media Organisation (LAMO) executive director and co-fouder Monisha Ahmed told The Federal.

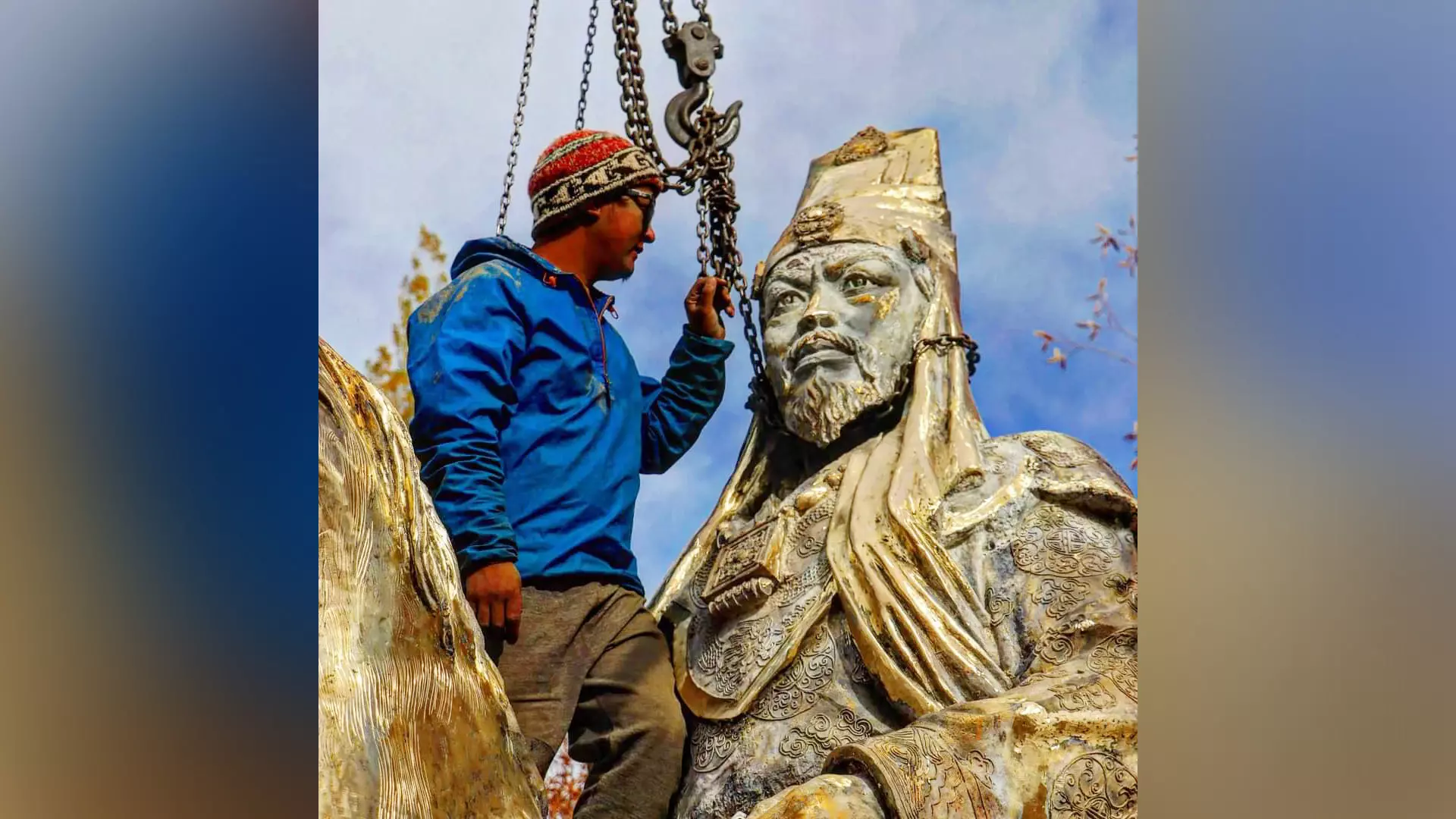

The grand statue of 17th century Ladakhi king Sennge Namgyal, the first metal casting work in the whole of Ladakh.

“One of the motives to co-organise Sā Ladakh festival was also to make it known that there is a contemporariness in Ladakhi art and there are contemporary Ladakhi artists who are doing good work and we need to recognise them,” she added.

Contemporary art has come to life over the last 15 years in Ladakh propelled by various art workshops and exhibitions. While artists have both individually and in groups tried to help each other create a new art movement through exhibitions and workshops, residential programmes for artists have been organised from time to time by the local and national art associations, giving artists platforms to ideate and exchange thoughts.

The new breed of artists has created a distinct identify by amalgamating the traditional with the modern.

In 2017, Tsering Gurmet Kungyam, who was then 27 years old, came back to Ladakh after completing his degree in Masters in Fine Arts from Banaras Hindu University. Back then he was among the few artists producing art works in Leh. Now, however, there are around 30 others in Ladakh who are working in the field of visual and creative art.

Gurmet recently made a land installation titled ‘The Bayul’, which, according to popular belief, are hidden lands that lie within the Ladakhi landscape and are not visible to the human eye. They evoke emotions of plenitude as folklores describe them as being lush and green with rich fields and ample water supplies. They are believed to be inhabited by fairies, dwarfs, and all kinds of supernatural creatures, who are also believed to protect the Ladakhi people. Humans have a curious reciprocal relationship with the imaginary inhabitants of the bayul. Interestingly, the real people of Ladakh have trade relations with the imaginary people of bayul. As part of a traditional practice, Ladakhis leave goods at designated places at night only to find the items replaced with other goodies in the morning.

One of Gurmet’s early works includes a grand statue of 17th century Ladakhi king Sennge Namgyal using metal. This is the first metal casting work in the whole of Ladakh. Gurmet did a lot of research on the facial and physical aspects of Sengge Namgyal as he is related to the King of Baltistan from the maternal side.

Tsering Gurmet Kungyam before the grand statue of 17th century Ladakhi king Sennge Namgyal, which he created using metal.

Gurmet is also credited with opening the commercial space in sculpturing and has made hundreds of commissioned sculptures in Ladakh.

“For an aspiring artist, money should not be the priority. It will come naturally if one has talent. One should work on their artistic growth and get due recognition with time for their art,” Gurmet told The Federal.

If it is folklore and history that Gurmet is working on, Jigmet Angmo is trying to highlight the issues of ecosystem fragility.

Jigmet, in her late 20s, is a Leh-based artist who has created an untitled land installation on the theme of fragility, encompassing the many dimensions of the issue. The importance of fragility of architectural structures in the Ladakhi landscape was never lost on Jigmet, but it assumed greater importance as she began creating her installation. Every evening, fearing rain, she covered her work with plastic bags. Then during the July cloud burst, she recalls rushing to help her father cover the roof of their own home with plastic sheets. This threw up a contradiction for her, how could plastic be bad when it also protects? And this was depicted in her land installation work.

Jigmet, like other contemporary artists, is self-taught. She came back to Ladakh in 2016 after finishing her degree in animation Maya Academy of Advanced Creativity (MAAC), New Delhi, and started doing paintings and working at LAMO as an intern. The opportunity helped her learn the nuances of painting and the space helped to nurture her artistic abilities.

Jigmet has created an untitled land installation on the theme of fragility, encompassing the many dimensions of the issue.

Her first work was a comic book titled Drugjonma, which was inspired by the folk stories of Ladakh. With time, her paintings started getting attention and during an exhibition at LAMO, she was able to even find a buyer for her painting. “LAMO made sure that my painting gets sold. It was very encouraging for me as an artist to continue my work,” she told The Federal.

The major influences in her art are folktales, architectural heritage and the landscape of Ladakh. One of her paintings tilted Nakpo Lchaksi Khar (Black Castle of Iron) was sold in London Art Biennial and received a lot of attention because it depicted the famous folk tale of Rgyalam Kesar. She painted a floating castle where a demon exists and the protagonist of the story, Kesar, goes in search of the demon.

Anayat Ali, a visual artist and graphic designer from Kargil, also presented a stone balancing art during Sā Ladakh that conveyed the message of the fragility of Ladakh’s ecosystem,

“The core art of stone balancing is about fragility which I related with the fragile ecology of Ladakh,” Anayat said. He added that apart from it, he had also made an animated film on the influx of tourism in Ladakh and its impact on the regions resources.

Anwar Hussain from Kargil, a fine arts graduate from Jamia Millia University, is also actively engaged in contributing to the contemporary art movement of Kargil. His art influences in painting are mostly from Ladakh’s heritage, culture, landscape, people. Anwar also draws from the tragedy of Karbala which has a deep influence on him.

There is a growing importance being given to sculptures.

Zahra Batul's creation chepu (Ladakhi basket), which is an attempt to save Ladakhi traditions.

Zahra Batul (27), the only female sculptor and artist, started working in Kargil two years back after finishing her Masters in Fine Arts from Baroda with specialisation in sculptures.

Zahra recently participated in a residency in Shantineketan Kolkata, organised by Achi Association, where she got to create art on chepu (Ladakhi basket). The idea was to create utensils from the weaving technique of Ladakhi baskets and create awareness around the declining heritage in Ladakhi kitchens. “A utensil used for pouring local alcohol in the art has been displayed with the baskets which have been abandoned by the Muslim community in Ladakh,” Zahra said.

“For me, the residency was a great opportunity, especially as a female artist coming from a Muslim-dominated place like Kargil, adorning Islamic attire. But the audience and artists were very encouraging towards me,” she said.

Abeer Gupta, an anthropologist and filmmaker who works with Achi Association India, curated a month-long series of residencies and workshop titled ‘Peripheral Visions: Journeys of Migration and Belonging’. The programme began on July 16.

Abeer said that the programme aims to spark a dialogue among artists from different parts of the Himalayan region like Nepal and Ladakh and create an environment to exchange ideas and conversations through art. These conversations have been very natural and fluid as the concerns were very similar across the region.

He said the residencies were going on at multiple places on different themes and at Spindle studio. They plan to bind all the works in a broad way to understand the wide umbrella under which they are looking at their landscape and the materiality of the landscape.

“The drawings of Pasang from Nepal were about a place called Dolpo. Pasang talks about the pastures and yak. Next to it, sculptures of Chemat Dorje were placed in which he created an iconography around the moon reflecting the concept of moon land and yak. This talked about pastoral lands, cross Himalayan movement and domesticated yaks,” Abeer said.

An art work presented at the Choskore House exhibition.

The art work at Tashi’s studio was concentrated more around identities — who we are, what does it mean to be a Ladakhi or what does it mean to be a Tamang person, and similarly what does it mean to a Muslim Ladakhi.

The Choskore House exhibition based on the theme of matriarchy, which was part of one of the residencies for Ladakhi artists, displayed works around conversations among women because women play a very important role in mountain societies.

Ladakhi artists feel presenting the region’s own art is important.

Abeer added that the Himalayan artists and Himalayan region have always been co-opted into the narrative of the mainstream. “What happens in this process is that the artists always have to become a participant of a narrative that they are being co-opted into but we have to see what does it look like when they (Ladakhi artists) have to set the narrative”?

Anwar Hussain from Kargil with his portraits on Kargil's pluralistic society.

“We are saying that this dialogue is something where we are developing curatorial boundaries from the inside and not trying to co-opt the Ladakhi artists into a narrative of which is based somewhere else.”

Describing the need for an insider narrative in Ladakhi contemporary art, Abeer shared a conversation with a fellow Ladakhi artist Tashi. He said, “Tashi has made at least 10 murals or paintings of Leh Palace and you can find at least 20 different representation of Leh Palace in his works.”

“Over the years, I have been asking him what his own take about the Leh Palace is.”

After many years of doing murals on Leh Palace, Tashi arrived at the conclusion that Leh Palace has become the iconic motif of heritage and everyone is using it without engaging with some of the real issues, and this very observation or take Tashi showcased in his painting of Leh Palace.

Contemporary artists are showcasing Ladakhi paraphernalia as well that are culturally important.

Chemat Dorje (34), founder of Spindle Studio based in old Leh town, started working with LAMO around 2010, even when he had not completed his BFA. He is a sculptor and Ladakhi spindle has always been seen in his works.

After working with LAMO for few years and developing an understanding of his culture, heritage, old town cultural motifs and architecture, he established a studio in old town by the name of Spindle Studio.

“In the beginning, no one pursued a career in fine arts. I was the first Ladakhi who studied sculpting,” Chemat said.

Chemat’s specialisation is in creative sculpture and is mostly inspired from Ladakh’s culture and landscape. He is the first artist from Ladakh who did a solo show in 2017 in National Academy of Art in Delhi, titled Constant Rhythm. His work is present in every important gallery across India and he has done group shows in various cities such as Delhi, Kolkata, Jammu and Mumbai.

He was selected as Emerging Artists of India by the Parfulla Dhanukar Art Foundation in 2023, from among 400 entries.

It isn’t just exhibitions, workshops and residencies which promise to boost the contemporary art scene in Ladakh. The Leh administration has promised 40 kanals of land for an artist’s village.

Chemat said the government has provided land for the artist’s village and work is going on it. He said there is also a requirement of a separate college of art and craft in Ladakh so that more people find an avenue to explore their talent and contribute to the field.

Monisha Ahmed, while sharing her journey, said she personally has seen the growth in contemporary Ladakhi art and the artists since 2010, and her journey with LAMO has progressed parallelly with the art movement in Ladakh.

An installation created by Chemat Dorje.

“Our main goal has always been to support Ladakhi artists and also to provide the artists a space, either for work; discussion, exhibition, workshop and artists residencies,” Monisha said.

She added that the art movement in Ladakh is a new phenomenon, which has, not completed its 15 years yet. “We all are in a learning process and we usually do mistakes as well, however what is important that we should not stop learning”.

In 2013, LAMO organised the first exhibition of the art works of contemporary Ladakhi artists. During the exhibition, catalogues were designed and prices were set for the art works which ranged between Rs 10,000 and Rs 70,000, mostly for painting followed by photography and sculptures.

“We also initiated the process of taking artists outside to present their work nationally and globally in order to increase more awareness about contemporary Ladakhi art.”