- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Violence and Hindus: Understanding Savarkar’s idea of Hindutva

Two decades ago, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883-1966) was not a popular figure in India, but today he is everywhere. There are streets, roads, lakes and parks which have been named after the ‘Hindutva’ ideologue. Mumbai’s Versova-Bandra Sea Link has been renamed as Veer Savarkar Setu. Hotels, cycle shops and studios have ‘Veer Savarkar’ on their name boards with photographs of the...

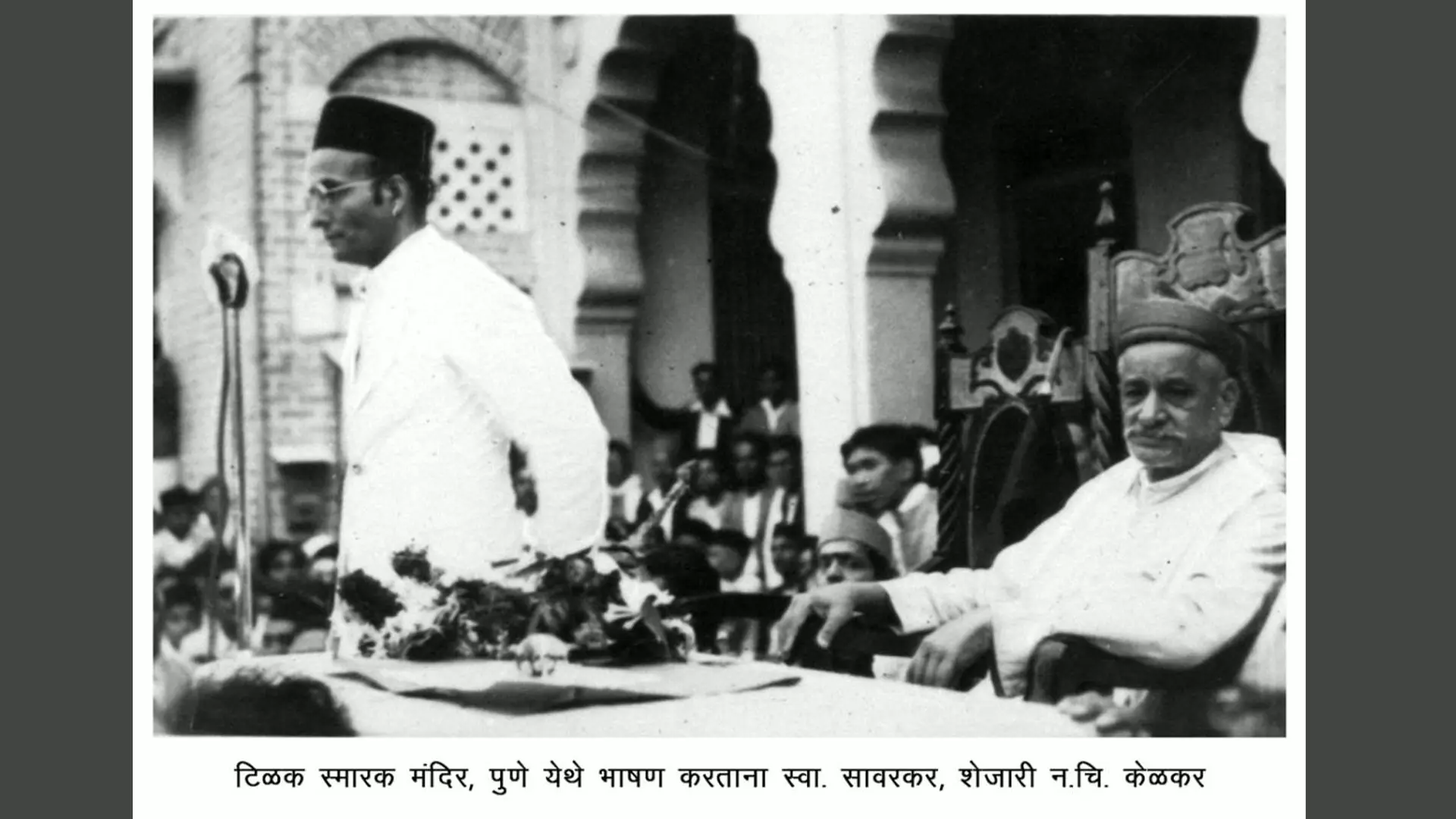

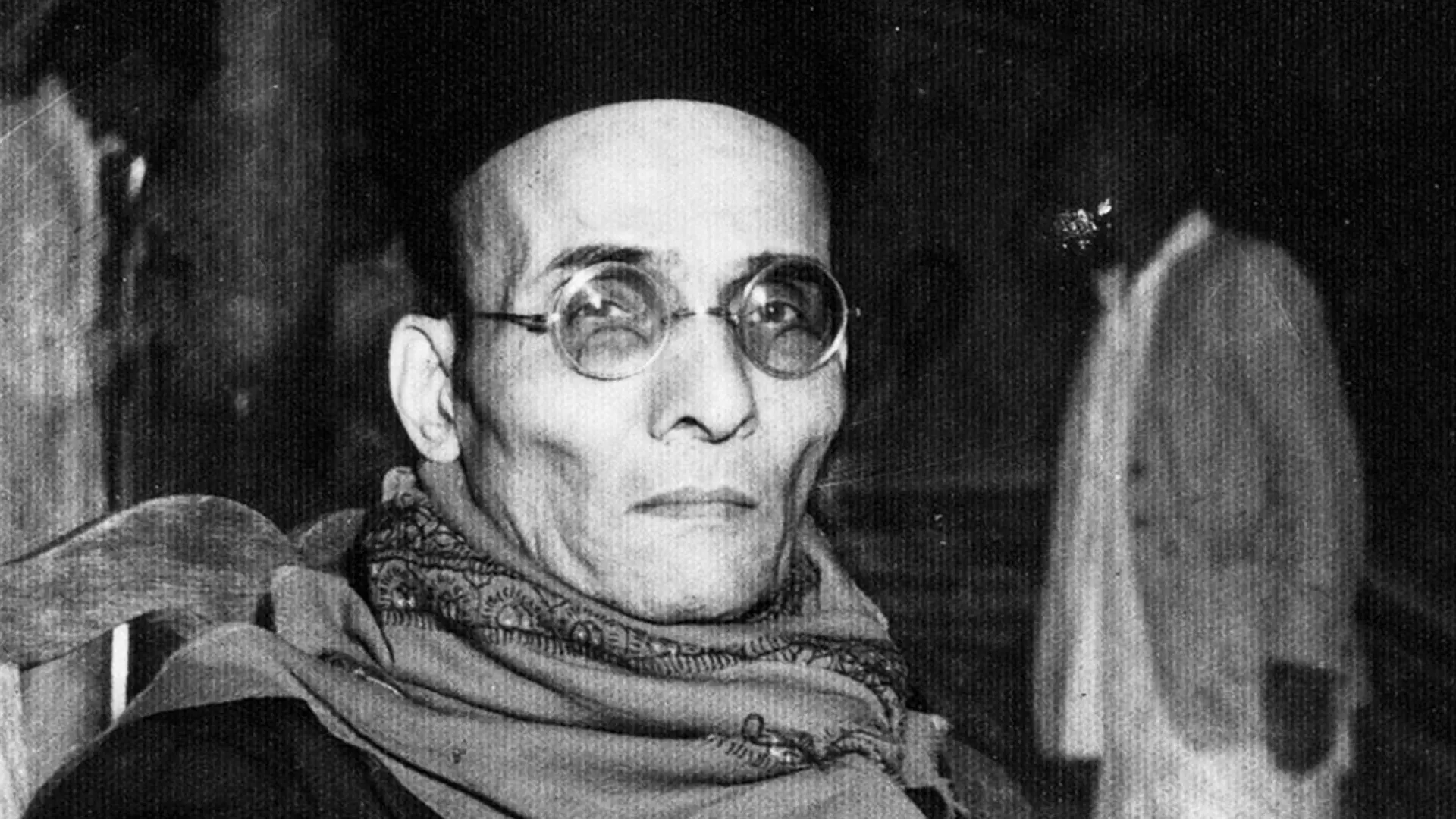

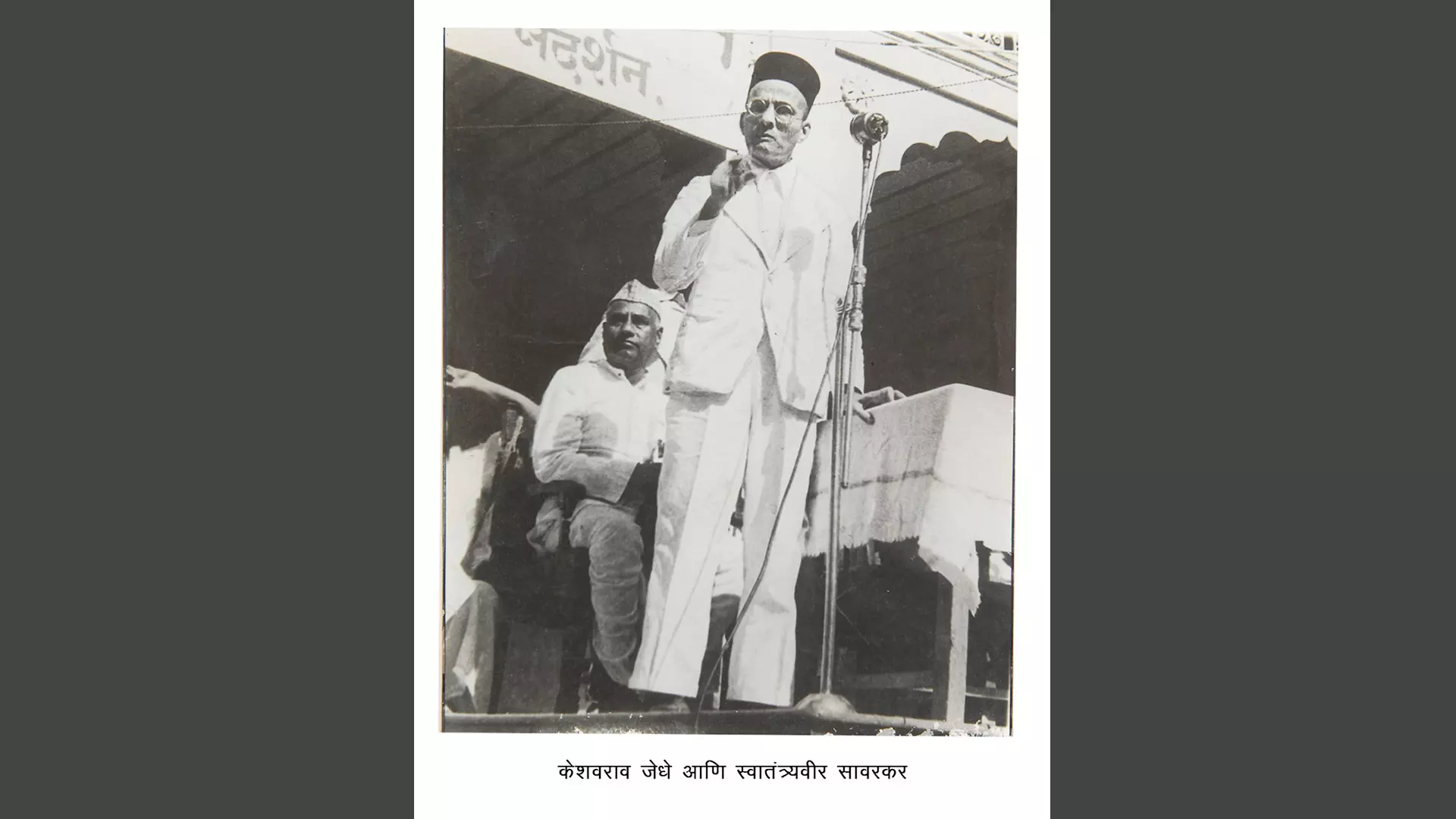

Two decades ago, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883-1966) was not a popular figure in India, but today he is everywhere. There are streets, roads, lakes and parks which have been named after the ‘Hindutva’ ideologue. Mumbai’s Versova-Bandra Sea Link has been renamed as Veer Savarkar Setu. Hotels, cycle shops and studios have ‘Veer Savarkar’ on their name boards with photographs of the Hindu nationalist in various shapes and sizes. A couple of months ago, the All India Hindu Mahasabha demanded that the image of Mahatma Gandhi on currency notes be replaced with that of VD Savarkar. Some historians believe that Savarkar may replace Gandhi if the BJP continues to be in power in India.

If you look at the political history of India, you will see that the ideologies of Savarkar have resurfaced today as never before. The transformation of Savarkar, however, was not an overnight affair.

Savarkar’s central claim that ‘Hindutva is not a word but a history’ was meant to demonstrate that he developed a conceptualisation of history as a way into the meaning of Hindutva, according to Vinayak Chaturvedi, author of Hindutva and Violence: VD Savarkar and the Politics of History, “For Savarkar, the purpose of this history was to trace key historical events to a powerful source — the font of motivation for historical actors who had turned to violence in a permanent war for Hindutva as the founding principle of a Hindu nation,” said Chaturvedi, a professor of history at the University of California, while speaking on “The Savarkar Moment: Reflections on Writing History and Violence,” organised by Karwaan: The Heritage Exploration, one of the country’s most active history collectives, recently.

Some historians believe VD Savarkar may replace Mahatma Gandhi on currency notes.

Even though the word ‘Hindutva’ was first used by Bengali nationalist Chandranath Basu in 1890, it was Savarkar who conceptualised what he meant by Hindutva in the 20th century. “Hindutva is a compound of two words (Hindu + Tattva (essence and essentials). It was not a religious or spiritual history. It was not a complete or total history but ‘a history in full’. However, it is an awkward construction in English,” said Chaturvedi.

Many scholars don’t understand exactly what Savarkar meant by Hindutva, which he defines in his book, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? published in 1923. “The first edition of the book was initially titled Hinduism, probably there was a misprint. You can see the corrections glued on top of the original title. The only place where I found it without the change is at the British Library. So a missprint still exists,” he said. In the first part of the book, Savarkar defines who a Hindu is and the essentials of being a Hindu. A Hindu, according to Savarkar, means a person who regards this land of Bharathavarsha, from the Indus to the Seas as his Father-Land as well as his Holy land that’s the cradle land of his religion.

For Savarkar, writing history was a holy work. And writing a history in full means tracing all the events back to the source and motive. How does one do it? Savarkar defines motive as the innermost desire of individuals (historical actors or desiring subjects). He used terms such as ‘heroes’, ‘veer’ and ‘brave’ to address these chief actors. For Savarkar, writing a history in full involves seeking out these heroes as a way to study their inner desires and motives. He says a historian must search for documents that reflect the essence of these desiring subjects. “Savarkar here is staking a claim that he as a historian can find these desiring subjects and he can tell you what their motive was. Even if they are not speaking he can speak for them. He is an omniscient narrator in that sense. And what he does in The Indian War of Independence, 1857, is that he talks about the fact (mutiny) and for him all these individuals are revolutionaries. He takes this methodology and applies it for thinking about Hindutva in his later works,” said Chaturvedi.

Savarkar was born on May 28, 1883 at Bhagur, a village near Nashik to a Chitpavan Bhrahmin couple. In his biography of Savarkar, Dhananjay Keer tried to link his birth with the death and birth of two international figures. “Seventy-five days before Savarkar’s birth, Karl Marx, the prophet of the Proletariat, passed away unnoticed in a London corner and 62 days after was born Benito Mussolini, who later moulded the destiny of Italy.” Savarkar passed his matriculation examination in December 1901, and left Nasik for Poona where he joined the Fergusson College in 1902. He founded Abinava Bharat, a revolutionary organisation, in 1904 and in 1905, he organised the first public bonfire of foreign clothes in Pune. After graduating from Bombay University in December 1905, he went to Bombay to study law. In 1906, he left Bombay for London on a steamer called ‘Persia’.

Savarkar was a man who has been both under-studied and oversimplified in the decades since his death, according to Julia Kelley-Swift. She said in the 30 years between his death and the rebirth of the Hindu Nationalist movement – in the form of the BJP – Savarkar’s image underwent a massive change. “During his lifetime, Savarkar was associated most strongly with his time as a young freedom fighter, and then later as president of the Mahasabha and possible accomplice in the murder of Gandhi. The importance of his tract, Hindutva was largely overshadowed by other, more public, aspects of his life. Since 1990, however, the ideas of Hindutva have re-emerged more prominently than ever, and Savarkar is being recognised far more widely for his work. In fact, there have been new editions of Hindutva published every two years since 1999, an indicator of the continued relevance and popularity of the tract,” writes Julia Kelley-Swift in her research thesis titled “A misunderstood legacy: V D Savarkar and the creation of Hindutva”.

In 2003, when Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee unveiled a portrait of Savarkar in the Central Hall of Parliament, many opposition leaders questioned it. Julia said even though the portrait – which sits directly across from that of Mahatma Gandhi – has raised a great deal of controversy since its installation, it stands as an indication of Savarkar’s rising prominence in today’s Indian politics.

If you read Savarkar, you will know how violence is central to his thought and to his understanding of how a Hindu should behave. He tries to redefine violence by saying that it is part of every human being. “Savarkar says ‘himsa’ (violence) is the nature of being a Hindu. Then what you can do is look for the events of violence. In Essentials of Hindutva, he says that the Hindus were the first to colonise the Bharathvarsh. It was the Hindu who were the first to do it. The Hindus used violence against non-Hindus in the act of creating this land. As a result, the non-Hindus became Hindus through this act of violence. So you have Hindus who are dominating other local populations and converting them to becoming Hindus through this act of violence. If that’s the case, the Hindu is both the perpetuator and the victim in the very act of becoming a Hindu. So the Hindu is both the perpetuator and the victim in Savarkar’s own narrative,” said Chaturvedi.

Savarkar also said ‘ahimsa’ (non-violence) is antithetical to being a Hindu. If you propagate nonviolence, then it becomes the opposite of being a Hindu. He discusses the famous story of Narasimha’s killing of Hiranyakashipu from the Hindu epic text Bhagavata Purana. Prahlada’s nonviolence did not resolve the problem, according to Savarkar. It was only when Vishnu took the form of a lion and not only killed Prahlada’s father but also brutalised him that the issue was resolved.

Savarkar’s first book was a translation of the works of Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872), an Italian revolutionary who was the founder of secret revolutionary society called ‘Young Italy’ and a champion of the movement for the unification of Italy called Risorgimento. Savarkar’s Mazzini, according to Dhananjay Keer, was the first book to enjoy an uncommon popularity in Maharashtra and at the same time was the first victim of the Indian Press Act. “The book was mostly loved for the introduction of the Indian Mazzini, expounding the great mission of the Italian patriot. The fiery propaganda and the burning patriotism pervading this immortal introduction captivated the minds of the people so much so that, though it was suppressed by the government, patriotic youths learnt it by heart and repeated the 25 pages of its inspiring introduction word for word. The book was restored in 1946 after having suffered proscription for 40 years,” writes Keer in the biography Veer Savarkar.

Chaturvedi, however, said Savarkar’s historical methodology was complex as he laid out multiple kinds of methodological strategies while being an omniscient narrator. “Using antonyms and conjectures, he believed that his claims are ‘true’ unless proven to be ‘untrue’. The recent Kannada text book for Class 8 describing how Savarkar flew on the wings of a bulbul bird to visit his motherland when he was imprisoned in the Andaman cellular jail shows the best example of the conjectures introduced by Savarkar,” he said.

Savarkar believed that he possessed the Hindu spirit which has been travelling across time and therefore he can talk to people in the past. He assumed the idea of the omniscient narrator as he believed that he could narrate what they were saying. He could feel what they were feeling and he could argue what they were arguing. “As an author who seeks the ‘desiring’ subjects, the two Hindus come together – the Savarkar who is the maker of history is seeking to write about the makers of history of these Hindu heroes who are brave and ‘veer’. And in that act, he becomes brave and ‘veer’. Today’s Hindu history writers who are writing about Savarkar become ‘veer’ and heroic in the act of writing. The cycle will continue,” said Chaturvedi, who is the author of Peasant Pasts: History and Memory in Western India (2007) and the editor of Mapping Subaltern Studies and the Postcolonial (2000) and The Pandemic: Perspectives on Asia (2020).

Savarkar also wrote about the obstacles Hinduism faced from other religions. The Buddhists, according to Savarkar, travelled all over the world and told them that India no longer has a theory of warfare. This in a way allowed lots of foreigners to come to our land. He believed that any Hindu who celebrates nonviolence is an effeminate Hindu.

When Savarkar was writing this the most significant leader who practised nonviolence was Gandhi. “In 1909, there was an interesting interaction between Gandhi and Savarkar in which they met at a conference. Gandhi said he will not participate in the conference if there was any discussion on politics. Savarkar said fine, however they discussed Ramayana and the necessity of the use of violence as an act in the epic and this became the first public interaction between Gandhi and Savarkar on the issue of violence in and of itself,” he added.

Chaturvedi shows how he (Vinayak Chaturvedi) was named after Savarkar by Parchure, a doctor in Gwalior, who had supplied Nathuram Godse the pistol that was used to kill Gandhi in 1948. The professor’s grandmother would take him to Parchure as he was weak and often fell ill as a child. It was during one of such visits that the doctor suggested he be named after Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. She was a little hesitant initially, but agreed to it later.