- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Valentine’s Day: If you’re a single seized by loneliness, watch how you feel

It’s that time of the year, again. It’s Valentine’s Day and love is in the air, with couples planning romantic getaways and public as well as clandestine displays of affection. In gardens and parks, and in the precincts of monuments and museums, lovebirds will be glued to each other, cosying up, and coochie-cooing for hours on end. In the nooks and crannies of cities that serve as...

It’s that time of the year, again. It’s Valentine’s Day and love is in the air, with couples planning romantic getaways and public as well as clandestine displays of affection. In gardens and parks, and in the precincts of monuments and museums, lovebirds will be glued to each other, cosying up, and coochie-cooing for hours on end. In the nooks and crannies of cities that serve as their haunts for the rest of the year, they will be seen holding hands, and leaning on and into each other. However, amid the flurry of heart-shaped chocolates and bunches/bouquets of red roses as love will rekindle and bloom between lovers old and new, the unattached and the singles will likely see their vital organ ache with undefined longing and a twinge of melancholy.

If you are among the lonely hearts in the throes of conflicting emotions, watch your negative feelings for they can impinge on your sense of self. For several decades, scientists believed that it was rational thought that had the dominant influence on our behaviour, warning us that if we brought emotion into the picture, it would most likely be counterproductive. However, as researches in recent years have shown, emotion — anxiety, fear, anger, rage, despair, and loneliness — is as important as reason in influencing our thoughts and decisions. What paths we choose to follow or what we make of ourselves is dependent on our emotion which, unlike reason that allows us to draw logical conclusions based on our goals, operates at an abstract level, affecting the importance we assign to those goals.

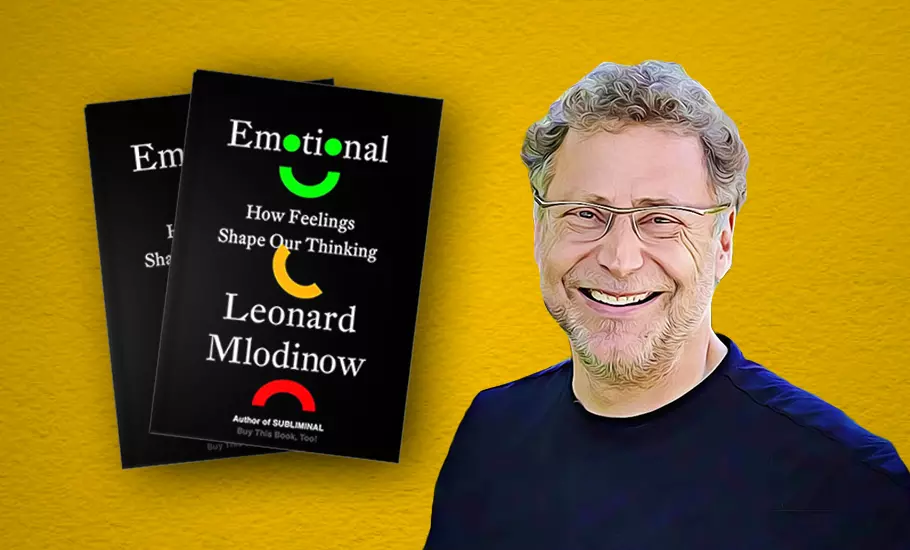

In the last three decades, there has been a revolution in how we look at the role of emotion in our lives. “Emotion changes the way we think about our present circumstances and future prospects, often in subtle but consequential ways. Much of our understanding of how that works has come from advances in just the last decade or so, during which there has been an unparalleled explosion of research in the field,” writes well-known American theoretical physicist, mathematician, screenwriter and author Leonard Mlodinow in Emotional: How Feelings Shape Our Thinking (2022). Mlodinow writes in detail how the recent breakthroughs in psychology and neuroscience have demonstrated the indispensable role emotions play in our overall well-being. A valuable addition to the corpus on the psychology of emotions, the book shows how our emotions can either assist or hinder us, and what we can learn from both experiences.

In the book Emotional: How Feelings Shape Our Thinking, Leonard Mlodinow writes emotion changes the way we think about our present circumstances and future prospects, often in subtle but consequential ways.

‘Emotion’ is derived from the Latin movere — ‘to move’, in English. Though it grew out of the work of Thomas Willis, a 17th-century London doctor who found that the deviant behaviours of many criminals could be traced to specific features of their brains, the modern use of ‘emotion’ first appeared in a set of lectures by Edinburgh professor of moral philosophy, Thomas Brown, which was published in 1820. The Greeks held that the mind consists of two competing forces: one that’s cold, logical, and rational, and the other that’s hot, passionate, and impulsive. For millennia these ideas informed not just the science of the mind, but also theology and philosophy. So much so that even someone like Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) incorporated this theory into his work. John Mayer and Peter Salovey’s theory of ‘emotional intelligence,’ which was popularised by Daniel Goleman’s 1995 book of the same name, is also partly based on it. It is the framework for most of what we think about our feelings, but Mlodinow argues that it is wrong.

Owing to the advances in neuroimaging and other technologies that have allowed scientists to look into, and experiment upon, the brain, the old theory of emotion is now giving way to a new view. Connectome, a kind of circuit diagram for the brain, allows scientists to navigate the brain in a way that was never before possible; they can now compare essential circuits and reach the specific regions of the brain to explore the cells that they comprise, and decipher the electrical signals that generate our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Advancements like optogenetics and transcranial stimulation offer much more. While the former enables scientists to uncover the micro-patterns of brain activity that produce certain mental states — fear, anxiety, and depression — the latter helps them assess the function of the human brain. They can now employ electromagnetic fields or currents to stimulate or inhibit neural activity in precise locations in the brain with no permanent effects on the experimental subject.

“These and other techniques and technologies have imparted so much insight, and given rise to so much new work, that a whole new field of psychology has emerged, called ‘affective neuroscience’. Founded on the application of modern tools to the age-old study of human feeling, affective neuroscience has reshaped the way scientists view emotion. They’ve found that while the old viewpoint offered what seemed like plausible answers to basic questions about feelings, it didn’t accurately represent the way the human brain operates. For example, each ‘basic’ emotion is not really a single emotion but actually a catchall term for a spectrum or category of feelings, and those categories are not necessarily distinct from one another,” writes Mlodinow.

Elaborating on how our emotion guides thought, the author recounts the deeply moving love story of Paul Dirac, one of the greatest physicists of the twentieth century, and a pioneer in quantum theory, whose theories have formed the basis of much that moves the modern world: electronics, computer, communications, and internet technologies. A genius at matters of logic, Dirac, born in Bristol (England), was emotionally autistic as a young man, utterly lacking affinity or emotion in his interactions with his fellow human beings. Since his Swiss father insisted that he and his siblings must speak in his native French and not English, Dirac grew up a reticent boy as he had trouble with the other language. As an adult, his life was coldly intellectual, devoid of joy, hope — and love. “My life is mainly concerned with facts, not feelings,” he would tell his friends. A chance encounter with his fellow physicist Eugene Wigner’s divorced sister, Margit — known to her friends as Manci, she had two young children, and no aptitude for science — changed him forever.

When they met in Princeton in 1934, sparks flew, and they continued to write and occasionally see each other. Three years later, they were married, with Dirac adopting Manci’s two children. The Diracs remained the centre of each other’s lives until Paul Dirac died in 1984, shortly after the 50th anniversary of their meeting. “In his marriage Dirac achieved a level of happiness he had never thought possible. Dirac’s feelings for Manci awakened him. Being out of touch with his feelings, Dirac had been living half a life. After finding Manci —and his emotional self — he looked at the world differently, related to others differently, made different decisions in life. He became, according to his colleagues, a different person. Once he discovered emotion, Dirac grew to love the company of others, and he realised the beneficial effect of emotion on his professional thinking. In his mental life, this was Dirac’s great epiphany,” writes Mlodinow.

Today, social media has created a false impression that makes us believe that we are all connected, but as a recent release, Kho Gaye Hum Kahan, shows, we have never before been so lonely. An affecting tale of three friends — one of them a woman (a terrific Ananya Pandey) — who find ways to stay together since their school days, even as they navigate their personal aspirations, and fall in and out of love outside of their circle of friendship. The film makes us question the pretentious lives that we live on social media. Our real life may be creased with a thousand worries, but that would not stop us from flaunting on social media that we are leading the perfect, happiest life. In the images of ourselves that we put out for the whole world to see, everything is hunky-dory. Even when we feel broken inside, we would rather put our smiling face forward.

Kho Gaye Hum Kahan shows how we have never before been so lonely.

Kho Gaye Hum Kahan, shows, we have never before been so lonely.

There is no doubt that love changes us, often for the better. But in the rush to find external validation through romantic partnerships, people should not overlook the profound importance of self-love. For those who walk alone, Valentine’s Day should be an occasion to lavish themselves with care and attention; they should embrace their worthiness and inherent value — ecstatically. After all, if lovers have their day, so do those who are emotionally adrift and unmoored, and like to stay with no strings attached: Single Awareness Day, celebrated the very next day (February 15), is for all those solitary souls who revel in isolation; they cherish their ‘me-time’ moments, and are often seized by a strong urge to tear themselves away and seek refuge in silence and solitude whenever they find themselves in the company of people, surrounded by endless chatter.

While popular culture is steeped in the notion that happiness is contingent upon finding a romantic partner, the reality is that singlehood offers its own unique joys and freedoms. As people who have chosen to or are forced to stay single will tell you, friendships, familial ties, and connections with pets can all serve as sources of love and companionship, enriching our lives in ways that transcend the confines of romantic entanglement. Freed from the constraints of a relationship, singles can prioritise personal growth, pursue their passions, and chart their own path in life. Whether it’s travelling solo, pursuing a career goal, or simply revelling in the freedom to be oneself, singlehood can be a time of self-discovery and empowerment.

Agreed that if you are single, and the world around you is soaked in the colour of love, it’s difficult not to crave for the significant someone with whom you can spend some quality time; the warmth of touch, the communion of lips and limbs. However, if you learn to love yourself, you can be alone but never lonely. Films and songs glorify romantic love as the ultimate pinnacle of human connection, but there exists a myriad of meaningful relationships that bring joy and fulfilment. On Valentine’s Day, singles can take solace in the fact that love comes in many forms, and each one is worthy of celebration.