- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Unequal lives: Why Gujarat donates fewer organs to baby girls than baby boys

Ranjana Zala’s daughter Pallavi was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease five years ago at the age of seven. Since then, she had been living on weekly dialysis until last year when Ranjana decided to donate her kidney to her daughter against all odds.Pallavi, now a 12-year-old girl, is living a normal healthy life like any girl of her age.“I like dancing and have asked my parents if I...

Ranjana Zala’s daughter Pallavi was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease five years ago at the age of seven. Since then, she had been living on weekly dialysis until last year when Ranjana decided to donate her kidney to her daughter against all odds.

Pallavi, now a 12-year-old girl, is living a normal healthy life like any girl of her age.

“I like dancing and have asked my parents if I can take dancing classes,” she shares.

“I enjoy my new-found freedom after being bed-ridden and sick for so long. I am making new friends and go out with them often. Earlier life was confined to home and hospital,” she adds.

Ranjana Zala, a 36-year-old resident of Surat, hails from a family of textile businessmen. She has been a housewife whose life revolved around taking care of her elder daughter who was diagnosed with a chronic kidney disease, Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis, that left her completely dependent on medical care for years.

“When Pallavi was seven years old, she fell sick for a few days. She was down with fever, had mild swelling in her hands and legs so we took her to a local physician and she recovered. We never thought it would turn out to be something so serious until she fell sick again and this time she stopped urinating. Her legs swelled a lot too. We rushed her to the hospital where a series of tests were done and we got a diagnosis declaring kidney failure,” recalls Ranjana.

“It began as a bi-monthly dialysis, a pile of medicines and monthly tests. But her kidney wouldn’t cope so it progressed to weekly dialysis. Pallavi was put on transplant list but we could not get a matching donor. After about a year of watching my daughter suffer helplessly, I suggested that my husband and I should get tested to check if we were matching donors. My husband was reluctant to get tested. I told my husband that I wanted to get tested,” she adds.

“My mother-in-law told me that I have a younger son and husband to take care of and besides I was quite young. So, I shouldn’t be donating my kidney to my daughter and let her remain on dialysis until she gets a donor. She told me my daughter was bad investment and that I needed to stay healthy for my family. Even my relatives tried to dissuade me whenever they visited,” Ranjana tells The Federal.

After almost a year of trying to convince her family, Ranjana went to a private hospital in Surat and got tested. A month later, Pallavi’s transplant surgery was scheduled at the Institute of Kidney Diseases and Research Center (IKDRC) in Ahmedabad.

In a similar story, 29-year-old Sejal, mother of a two-year-old girl child travelled from her home in Junagadh to Ahmedabad for the kidney transplant surgery of her ailing infant daughter.

Sejal who hails from an agrarian family in Junagadh was referred to Ahmedabad civil hospital after she developed a complicacy in her pregnancy. Her daughter was born two days later with a congenital kidney defect and was put on neo-natal dialysis unit.

“Doctors told us that her kidney will never function on its own and she needs transplant. We were also told that I was a match and could donate my kidney. But my husband flatly refused and told the doctor that she (our child) will wait on the transplant list. When I insisted, he told me that wasn’t my decision to make,” says Sejal, who has two sons and parents-in-law that she takes care of back at her family home.

“We went back to Junagadh with our daughter. I was her primary care giver and would take her to Junagadh Civil hospital for her monthly dialysis. It took me two years to save some money and gather courage to take my daughter to Ahmedabad alone to get the kidney transplant. I told my elder son to tell his father that I am going to Ahmedabad. I knew he would get angry but I had to save my daughter. The only thing I regret is not doing this sooner. My daughter was left to suffer for two years when she could have got a kidney transplant and lived a normal life earlier,” she shares.

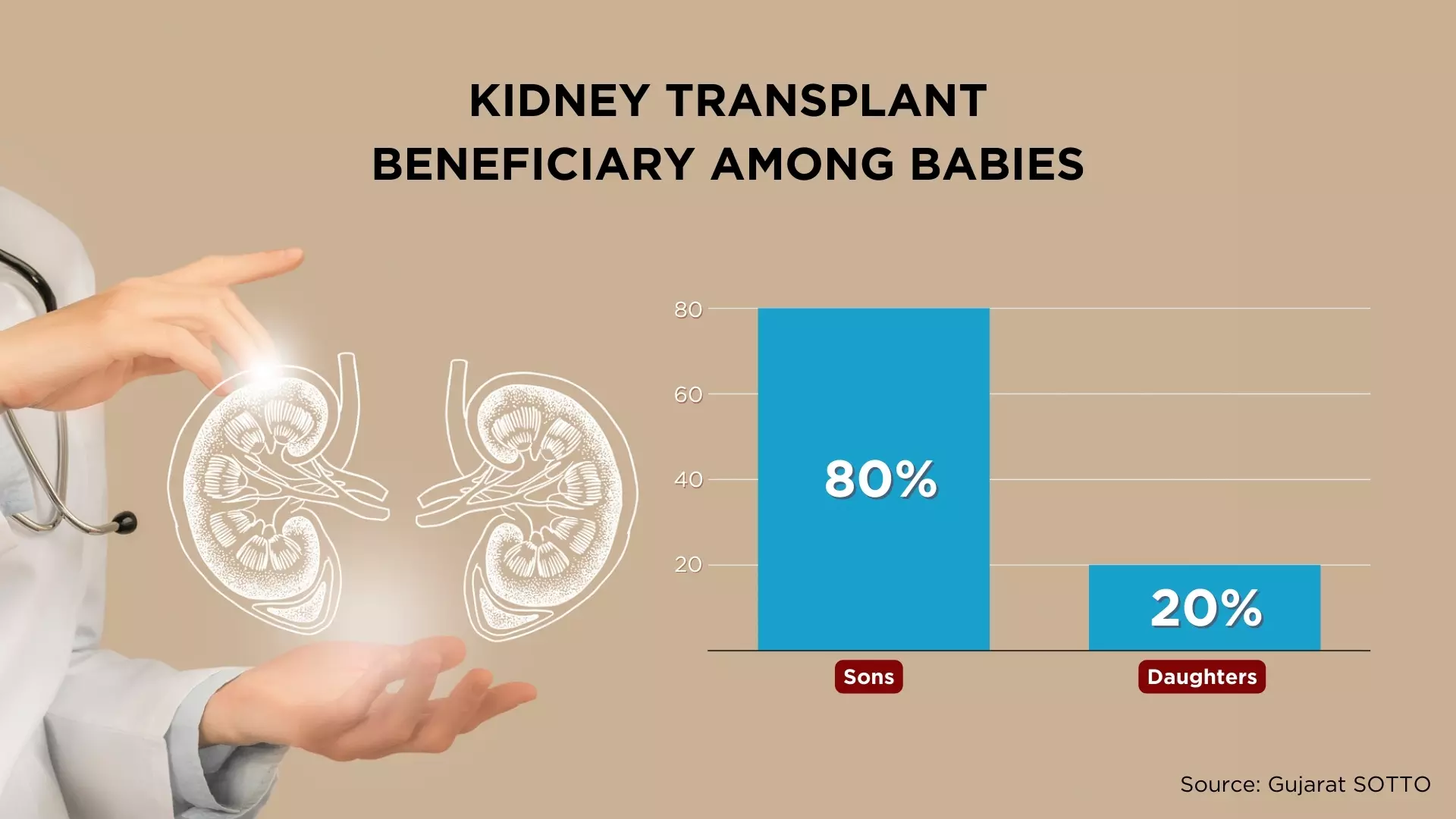

Noticeably, as per the data from the Gujarat State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (SOTTO) in Ahmedabad, 80 per cent of kidney transplant beneficiaries were sons while only 20 per cent were daughters. Amongst the female children, while 35 per cent of them are on dialysis, only 26 per cent make it to the waiting list. Finally, only 20 per cent get a kidney transplant.

Moreover, out of the 89 kidney transplants in female children, 29 came in from cadaver donors and 60 from living donors. Out of the 60, in 40 cases kidneys were donated by the mothers, two by grandfathers, five by grandmothers, 11 by fathers and two by extended family members.

A data released by IKDRC, over a period of 22 years — from 1999 to 2020 — reveals that 439 kidney transplants of pediatric patients (children) took place at the hospital. Out of these, 350 were boys under 18 years of age while only 89 girls went through transplantation in the 22 years.

“Usually, we see 25 to 45 pediatric transplants a year of which only 2 to 3 are females because mostly the families choose to leave them on dialysis. Everyone rushes to give organs to sons but there is so much reluctance to do the same for daughters.” Doctor Kinari Vala, associate professor of paediatric nephrology and a transplant surgeon at IKDRC told The Federal.

“Although we have been trying our best to convince parents to put their daughters on the cadaver waiting list so they may at least get a chance to receive a donated organ from a deceased donor, but parents show reluctance to avoid the treatment cost of an ailing daughter,” she adds.

“There is definitely gender disparity when it comes to donating organs to our girl child. Due to this a girl child suffers more than a male child even though girl children are more likely to develop chronic kidney diseases (CKD). Every child on dialysis needs a kidney transplant. It is because their kidneys are not doing the job that they need dialysis in the first place. However, even though both dialysis and transplant for children are free of cost in Gujarat under the State Health Plan Scheme, parents don’t often agree to put their girl children on the waitlist for a transplant,” said Pranjal Mody, the convener of Gujarat State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (SOTTO) and transplant surgeon.

“In a country when birth of a daughter is still considered to be a burden, a sick daughter is the last thing a family wants. I have witnessed cases where female new-born babies with congenital defects have been abandoned in the hospital by the family. In some cases, it is mostly the mothers who refuse to give up on their child and fight back,” Nilesh Mandlewala, an activist and head of Donate Life NGO tells the Federal.

A nationwide phenomenon

Noticeably, the gender disparity in pediatric organ donation is not limited to Gujarat. As per the data from the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (NOTTO), four out of five organ recipients in India between 1995 and 2021 were male children.

Out of the total 36,640 patients who underwent the transplants, 29,695 were male children, according to the NOTTO data on gender break-up of the cases. The data also reveals that 93 per cent of organ donations come from living donors who are women.

“When it comes to children, women are driven by a maternal instinct to save their children. While for fathers, it is a bad investment to go through a surgical procedure for a girl child. On the contrary, in cases where the male child has been sick and in need of organ transplant, mothers are put up to go through the procedure even without their consent. The families want to save the male child, the feeling isn’t reciprocated for a female child,” says Mandewala.

“In a case that we helped in the year 2022 in Surat, a woman was not a match for her male child who was born with kidney defect. But she was put up for transplant anyway despite being weak after the process of a complex child birth. In an exchange, her kidney was donated to a 46-year-old patient, whose wife’s kidney matched with her son. Both the women had no say in the process as men of the household agreed upon the arrangement,” he adds.