- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How a chain of community-led libraries is reimagining public reading spaces in Delhi-NCR

The Community Library Project (TCLP) began with the idea that a library could be free, non-discriminatory, inclusive and led by those it serves. Today, with reading circles, rap performances and literacy programmes, TCLP is a space for thousands to read, learn and organise together.

Ask anyone to name the first thing that comes to mind when you mention a library, and chances are that other than the obvious books, they would mention silence. It’s a word we have seen carved on a wooden plaque at the entrance or on a small tablet on the librarian’s desk across libraries. But inside The Community Library Project’s (TCLP) three facilities in Delhi, silence is rare,...

Ask anyone to name the first thing that comes to mind when you mention a library, and chances are that other than the obvious books, they would mention silence. It’s a word we have seen carved on a wooden plaque at the entrance or on a small tablet on the librarian’s desk across libraries. But inside The Community Library Project’s (TCLP) three facilities in Delhi, silence is rare, replaced by the sounds of shared reading, discussions, laughter and the rustle of books that belong equally to everyone who walks in.

TCLP began with a group of children gathered on the floor of the Ramditti JR Narang Deepalaya Learning Centre —an NGO in Delhi’s Panchsheel Vihar — listening to volunteers read stories. From those early circles grew a radical idea: that a library could be free, non-discriminatory, inclusive, feminist and led by the very communities who had most often been excluded from public reading spaces — backwards castes and classes and economically weaker sections of society.

In 2014, TCLP’s first library came up in Panchsheel Vihar, which later shifted to Khirki Extension. Writer Mridula Koshy was the first director and regarded as one of the brains behind the launch of TCLP. The second library was opened at Sikanderpur in Gurugram in 2017 and the latest facility was set up at South Extension’s Kotla Mubarakpur in 2021. The three libraries, operating in modest neighbourhoods of Delhi-NCR, serve more than 14,000 members – all free of cost.

TCLP had started out as a part of Deepalaya, but after the NGO closed during the Covid pandemic, it became an independently-run facility and continues to function as such.

https://youtu.be/unJNZBQl4hg?si=pawfMXEjd0rwXTrG

The library’s work is strengthened by organisational partners and a wide network of donors. Partnerships are renewed each year and currently TCLP has CSR partnerships with Penguin Random House, Reliance Foundation, HarperCollins, Wipro, and Nilekani Philanthropies, among others. Additionally, more than 100 writers, artists and civil society members are individual contributors to the library.

One such donor is writer Annie Zaidi, who says not only is the TCLP vital to the NCR area, but also that it was important to replicate many more such projects across the country. "India deserves free and well-maintained libraries in every city and village. For a democracy to remain functional, it is imperative that all citizens have free and equitable access to books, free or affordable cultural events, as well as a safe and sustainable space where they can read or find internet access if they don't have it at home. This is especially important for women and children. Ultimately, this will also be beneficial for media, publishing and the performing arts industries. In a country where three meals a day are difficult for the majority of people, we cannot expect that everyone will be able to buy books or pay for cultural access. We must enable everyone and I think The Community Library Project has shown us that it can be done," says Zaidi.

Her opinion on the TCLP's significance is shared by fellow writer Githa Hariharan.

"The big wide world of books to be discovered on your own, or with help and right in your community: can you give a child (or someone older) anything better? This is what The Community Library Project does. Its movement for free, publicly owned community libraries brings to every child and adult, whatever their background, the joy of reading and lifelong learning," says Hariharan, an annual donor to TCLP.

Donors may contribute to the TCLP in the form of books or funds for operations or both.

Also read: 10 years of Constitution Day: Why it risks becoming a masking ritual for a backsliding democracy

According to the TCLP website, the library’s vision is to "strive for an equitable and thoughtful society by expanding access to books and by promoting critical and imaginative thinking". Its "goal is to build a society characterised by increasing freedom to introspect, become self-aware, debate and express ourselves”.

“We felt that the need for a library was very urgent. These days, children stay glued to their mobile phones. But we have seen here that if you give young people access to books and make reading and learn interesting and fun, it opens all kinds of possibilities,” says Shaoli Dutta Haldar, a trustee of TCLP, who has been associated with the library since 2015.

Children engaged in reading at TCLPs Kotla Mubarakpur facility. Photo: Aranya Shankar

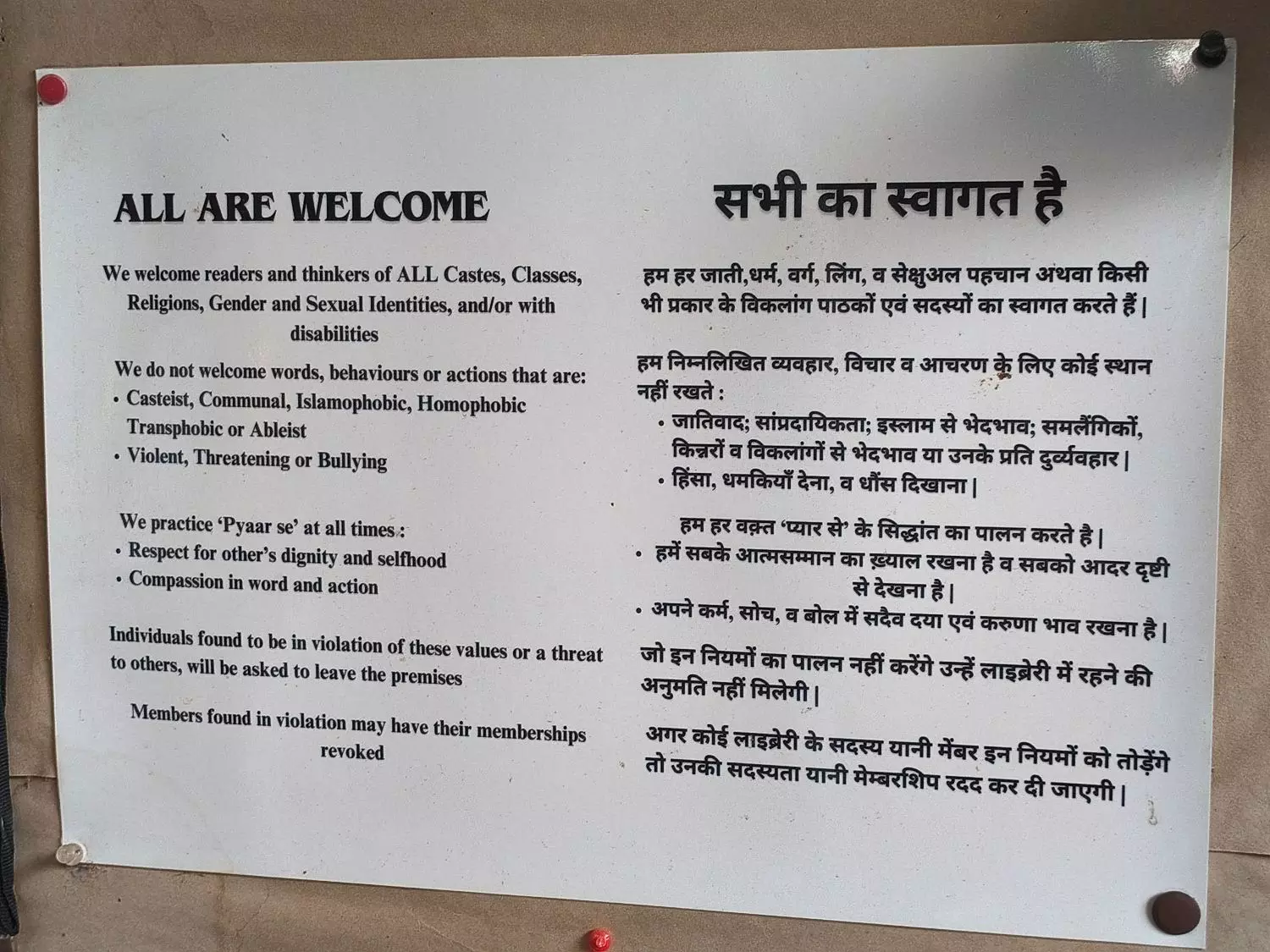

The library remains open from 12 PM to 8 PM, six days a week, with the 5 PM TO 8 PM slot reserved only for adult members. All three TCLP facilities are closed on Fridays. The library’s philosophy and ideology are pasted on their notice board, for all to see and imbibe. “We welcome readers of ALL castes, classes, religions, gender and sexual identities, and/or with disabilities,” it reads.

Rukshana (41), who works as a librarian assistant at the South Extension branch after years as a make-up artist in a salon, wears a hijab. Inside this library, though, it has never drawn a second glance, she says.

At the Khirki library, some notices are also written in Persian and there is a separate section of Persian books, as many Afghans are members of the library. Some of them are now even working with TCLP in various capacities. “When I started as a member, I didn’t even know about the caste system [in India]. It is through the library that I learnt so much about these concepts,” said an Afghan refugee in Delhi, who didn’t wish to be named.

On any given day, the libraries exude the warmth of a family drawing room, offering a mixed-bag of activities and conversations: young children tugging at librarians for stories, older readers preparing for exams, women gathering for the weekly reading circle and members drifting between books, newspapers, discussions, and tea.

In that sense, TCLP truly serves as the third space in society — the first two being home and office. Here, beyond reading, people meet and exchange ideas, with the library becoming a site for the imparting of knowledge and a tool for social integration.

Behind the library’s daily rhythm is a leadership structure intentionally built from within the community. A six-month Leadership Development Program run by the TCLP trains young members – many from Dalit, Bahujan and working-class backgrounds—as librarians, facilitators, digital storytellers, reading instructors and organisers, to staff the libraries. Their perspective shapes TCLP’s identity as a space that is progressive not only in content but in control.

The biggest example of this is TCLP director Mausam (identified by first name only), a 25-year-old, who joined the library as a member 11 years ago and now leads the organisation. As a child, she remembers being scared to enter a park near her house (she doesn’t wish to identify the area) called the ‘Chauhan Park’, where anyone who wasn’t a member of the Chauhan community (an upper caste) was allegedly stopped from entering.

Although not from a disadvantaged caste, Mausam belongs to a working-class family of migrants from Bihar. That experience, she recalls, made her realise at a young age that some places could only be accessed by certain people. It was when she started visiting the TCLP’s Panchsheel Vihar branch that her unlearning began.

A notice at the Khirki Extension library, welcoming everyone to the facility — a declaration of the TCLP's inclusivity. Photo: Aranya Shankar

“There was a common view among people around me that reservations [for backward castes and classes in jobs and education] are bad. It was when I came here and interacted with people that those views were challenged, and I learnt why they are important. Being a girl, I had faced discrimination in various ways, but it was when I started spending time here that I learnt what patriarchy was and why I had those experiences,” she says.

Among her favourite books are the Annihilation of Caste by B R Ambedkar, Sultana’s Dream by Begum Rokeya and a children’s book called ‘Paro Ki Kahani’ by Sugra Mehdi, in which a young girl, suffocated by domestic chores, runs away and becomes a rickshaw puller.

TCLP’s collection has more than 45,000 such books across languages, arranged on open shelves - one of its core principles. These include both donations and procurements. The books range from picture books and early readers to young adult fiction, nonfiction, graphic novels, Ambedkarite writing, books on secularism, Palestine, gender and contemporary literature. The curation balances community demand with texts that provoke thought.

Also read: Why ongoing Kannada Sahitya Parishat row reflects a deeper decline in century-old institution

Running through all the libraries is a deep belief: reading is thinking. TCLP treats literacy not as a skill alone, but as a form of empowerment and political participation. This is what differentiates TCLP from an NGO, claims Mausam, drawing a distinction between charity and work, which makes people aware of their rights and helps in their upliftment.

“The Community Library Project believes that libraries belong to the people they serve. Our spaces are built, run, and sustained through the collective efforts of readers, volunteers, and communities. We reject charity models and work instead toward shared responsibility and decision-making. When communities take ownership of their libraries by reading, organising, teaching, and caring for books, they also claim ownership of knowledge and the right to imagine their own futures. Community ownership ensures that the library remains free, inclusive, and accountable to the people, not to profit or power,” she says.

The TCLP’s Curriculum Department runs structured programmes like Learn to Read, Reading Fluency, and Early Literacy, where children recorded measurable gains: over 13 words learnt per child per minute on average last year. The libraries also hold spaces that go beyond reading. There is the Cyber Project, under which members get hour-long laptop access, with some slots reserved for women and transgender members. Shaam Ki Library stays open late for young adults, working members, and exam aspirants. The Women’s Reading Circle creates a room where women — often working long days and rarely claiming time for themselves — read, watch films, talk freely about books and gender, and discover new ways of seeing their lives. The once-a-month Bindaas Shaam brings even those who cannot visit regularly, offering an evening of stories, conversation, and reflection.

Members access laptops under the TCLP's Cyber Project. Photo: Aranya Shankar

For many members, TCLP has brought exposure they never thought possible. Priyanshi Gupta (18), a student of Gargi College, stays near TCLP’s South Ex branch in a paying guest accommodation. A member of a family with modest means in Uttarakhand, she would often visit the Kotla market to buy fruits at cheaper rates than those available near her residence. The library happened to be on her route.

“I had always been interested in books as a child and when I saw this library, it felt like the perfect fit. I needed a place to study for my course and also prepare for the UPSC [Union Public Service Commission entrance examination], but I couldn’t afford to pay for a library. This place has not only given me the space to do that but, through their initiatives, also encouraged me to present my poetry, which I never thought I would get a platform to share,” she says.

Ankit Kumar (21), who’s been frequenting the Khirki branch since 2023, says he finds a sense of equality here that he doesn’t elsewhere. “Even if the library is free, they don’t let you feel that they’re doing some charity or favour. If you ask for a book and they don’t have it, they will try to arrange it from some other branch,” he says. Kumar’s favourite book, which he discovered through TCLP, is Premchand’s Rangbhoomi.

During the pandemic, TCLP expanded its online world through Duniya Sabki, a digital library of “video and audio read-alouds, as well as links to books, magazines and other texts sent by WhatsApp to over 2,000 members three times each week”, which is also available on YouTube, SoundCloud and the TCLP website.

The arts are central to TCLP’s ideology. Through Khyal, the organisation hosts authors, performers and educators to talk about literature, caste, access and creativity. And from within its ranks, performers have grown.

Piyush Mahto (19), whose mother is an Adivasi and father an OBC, found an expression for his feelings through the library. Like Mausam, he too started as a member and is currently an intern at the Sikanderpur branch. Now, along with managing the library, Mahto also writes and performs rap songs – many questioning the status quo.

In his rap ‘Aazadi’, he writes: ‘Naam ka azad, azadi hai door. Neta bane baap, labour majboor… par uthegi aawaam, giregi deewar, jab goonjegi galiyon se ek hi pukaar – aazadi (Free only in name, real freedom is far. Leaders turn into fathers, labourers stay bound… But the people will rise, the walls will fall, when one cry echoes through the streets – freedom).

A placard extolling the virtues of reading at TCLP's Kotla Mubarakpur library. Photo: Aranya Shankar

Kilometres away, in the South Extension branch, 24-year-old Shivek Kumar, the librarian of this library and the son of a driver from an Adivasi family, is also making rap music. One of them, called ‘Kitaabe Bolti Hain’, is an ode to TCLP. It goes: “Kisi ke baat mei na aana duniya jhol si hai. Bajne do bajta toh dhol bhi hai. ek raaz jo yaha pe sadio se chipa tha, library aake dekho kitabein bolti hain. Don’t believe every word; this world is a bit of a con. Let it ring; after all, even a drum beats on. A secret kept hidden for centuries, walk into the library, and you’ll hear the books speak).

The journey, however, has not been all smooth. More than one TCLP branch faced threats from the local community and local politicians, for encouraging the mixing of boys and girls, and teaching about patriarchy, social justice and secularism, say TCLP leaders. Mausam, however, insists it has kept them undeterred.

“We believe in what we do and we will continue to do it,” she says.