- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

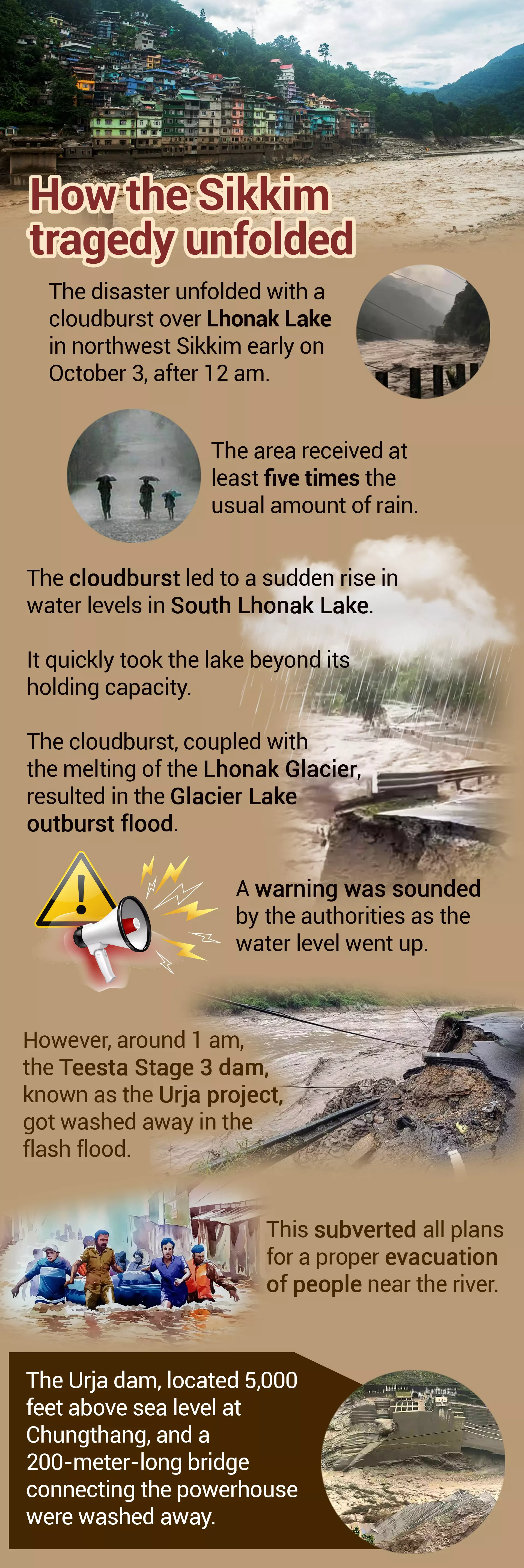

Around 10 pm on October 3, when the first waters came gushing in, Colonel Ranveer Singh Jamwal was bivouacking along with a team of 20 at the foot of Mount Jongsong in north Sikkim. Being trained mountaineers, the team members gathered all their stuff in the next 10 minutes and, following a mountaineer’s instinct, ran uphill.“And that window of 10 minutes and running up to the hills,...

Around 10 pm on October 3, when the first waters came gushing in, Colonel Ranveer Singh Jamwal was bivouacking along with a team of 20 at the foot of Mount Jongsong in north Sikkim. Being trained mountaineers, the team members gathered all their stuff in the next 10 minutes and, following a mountaineer’s instinct, ran uphill.

“And that window of 10 minutes and running up to the hills, rather than down, saved us,” Col Jamwal told the media reminiscing about the about the sudden tragedy.

It is only later that Col Jamwal would find out that the glacial South Lhonka lake, 4 km from India’s border with China, had burst leading to an unprecedented deluge in the area, and water gushing in his camp area.

While Col Jamwal and millions in Sikkim were caught by surprise by the incident, a study by the Sikkim State Disaster Management Authority had pointed to the danger that a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) in South Lhonak Lake could pose in August 2019.

The lake, spread over an area of 160 hectares, at an altitude of 5,245 metres in north west Sikkim, was “highly vulnerable” to GLOF events and could cause extensive damage to life and property in downstream areas, the study noted.

“Flash flood in downstream areas, likely damage to important infrastructure like dams and power houses, townships like Chungthang, Dikchu, Singtam, Rangpo are vulnerable and loss of life and property are likely.”

The study suggested diverting the lake water as the most viable option to mitigate the risk.

The study gathered dust till the intervening night of October 3 and 4, when its warnings came true.

Scientists have suggested that a strong earthquake that hit Nepal on October 3 could have damaged the embankments of South Lhonak Lake, causing the glacial lake outburst. The Central Water Commission has said that after the outburst, the size of the lake reduced from 160 hectares to 60 hectares. The volume of water stored in 100 hectares breached the embankment.

The National Remote Sensing Centre ISRO in a satellite-based study of the lake outburst noted: “temporal changes in the lake area on September 17, September 28 and October 4.” What precipitated the crisis is heavy rainfall Sikkim received between October 2 and October 5, raising the level of water in the dam.

The raging Teesta at Singtam.

Experts warn that the underlying cause of the incident is global warming and more such incidents are likely in the near future as with the rapid melting of glaciers in the Himalayan region, all glacial lakes are becoming vulnerable to bursting as they are increasing in size.

These experts are thus raising a serious question over whether it is at all prudent to set up large hydropower projects on rivers that emerge from this glacial region.

Over four decades, as climate change accelerated and the glacier began to melt, the South Lhonak lake at 5,200 m in the eastern Himalayas, grew nearly 10 times in size, from the size of 33 football fields to nearly 300. This change, considered unusual in geological terms, drew the attention of many scientists. A decade ago, a report in the journal Current Science warned of its “hazardous nature” and its potential for downstream devastation.

For people living downstream in the four districts of Mangan in north Sikkim, Gangtok, Namchi and Pakyong, the consequence of the Sough Lhonak lake burst has been disastrous. As the water from the lake made its way into river Teesta flowing down below, it swelled by 50 to 60 feet; sweeping away everyone and everything that fell on the way — men, buildings, roads, bridges, the 1,200 megawatt (MW), six-year-old Teesta Stage III hydroelectric project, army trucks and ammunition depots.

About 50 km downstream, the water flow overwhelmed the 510 MW, 15-year-old Teesta Stage V dam. Another dam, the 500 MW Teesta VI, 70 km further downstream from Stage V, suffered major damage. The concrete flowing with the water wreaked havoc on everything that came in its way.

These dams, some of them set up violating norms, and ignoring scientific warnings and local protests, were built because the Sikkim government hoped they would be revenue sources. But the opposite appears to have happened.

The destruction

According to government data, a total of 40 people were confirmed dead and 76 were missing. Days after the flash flood, bodies were located in Bangladesh, downstream of river Teesta, and handed over to the Indian authorities. Given this fact, authorities fear there is little chance of locating the missing persons or their bodies.

People who died were struck by the mighty river early on October 4 while they were still asleep. Among them were also 23 Indian Army jawans. Somewhere near Singtam, these jawans were also bivouacking for the night close to the Teesta riverbed. They were all washed away. Their vehicles, big trucks and other belongings, were later dug out of sand on the Teesta riverbed.

“Release of water from the Chungthang dam led to a sudden increase in water level up to 20 feet high downstream. This has led to army vehicles parked at Bardang near Singtam getting affected,” the Eastern Command of the army said in a statement on October 4.

A subsequent government release said: “Silt and mud up to 30 to 40 feet high has deposited and most of the vehicles are buried underneath. A massive search and rescue operation has been launched by the army and the Border Roads Organization.”

Vast stretches of the urban areas of Rangpo and Singtam were completely submerged under flood water.

People try to escape a flooded area on a lorry in Kalimpong.

When the flood water receded and mud and slush began to clear, many stories of devastation surfaced.

One heart-wrenching story was of Mohammed Mokhtar, a resident of Maharaja Colony of Rangpo, who clung to a tree and helplessly watched his three children being swept away by the floodwater as his house was completely submerged. The body of his son was found floating downstream later in the day.

The Teesta Bazar area in the Kalimpong district of West Bengal was also hit, with deaths and damages to several buildings.

With vital roads and bridges washed away, about 3,000 tourists were left stranded in the tourist hubs of Lachen and Lachung in north Sikkim. The Indian Air Force and army helicopters made multiple attempts to rescue them. For the first few days, bad weather interfered with the rescue efforts as choppers could not fly. The last of the stranded tourists could be rescued only about 10 days after the disaster had struck. The restoration of roads to Chungthang, Lachung and Lachen may take one and a half months, the construction of the bridges washed away will take longer. For now, authorities are erecting numerous Bailey bridges to restore connectivity temporarily.

The damage to infrastructure in Sikkim, a strategically important state on the China border, has been immense. National Highway 10, the lifeline of Sikkim, connecting Gangtok to Siliguri in West Bengal, was badly damaged in a number of places. At Setijhora, a particularly vulnerable stretch of the road running through the Kalimpong district, the road formation was completely washed away.

At Rangpo, the gateway to Sikkim, the national highway went 10 feet under accumulated mud and slush. With fresh landslides that followed the October 3 lake burst, even a one-way traffic for small vehicles on NH 10 has not been restored so far. Vehicles bound for Sikkim and Kalimpong are taking an alternative route, long and circuitous, via Gorubathan and Lava.

While the army ammunition depot in Munshithang was completely destroyed in the flood, weapons, ammunition and explosives were carried and deposited downstream, posing an added risk to the local population.

Downstream of Teesta at Kranti in the Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal, two children were killed and two others seriously injured when they tried to fiddle with a mortar shell floating in the river.

Faulty construction

Perhaps the most important cause and consequence of flash flood has been the washing away of the Teesta Urja Stage III dam of the giant 1,200 MW power project at Chungthang. It has left a serious question mark on the advisability of building large hydropower projects along the course of river Teesta, or for matter along the course of other rivers in the Himalayas.

Summing up the factors leading to the outburst of the South Lhonak Lake and the damage that was experienced in Teesta Urja Stage III, Sikkim Chief Minister Prem Singh Tamang said, “Preliminary reports suggested substandard quality followed during the construction of the Chungthang Dam, Stage III, resulting in the flood situation taking a catastrophic turn.”

He has said an inquiry committee would be set up and those found guilty would be brought to book, reminding that the dam was commissioned in 2017 when the previous Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) government was in office.

Later, an activist of the ruling Sikkim Krantikari Morcha (SKM) filed a police complaint against former Chief Minister of Sikkim Pawan Chamling who is now the president of SDF.

Sikkim embarked on its hydropower push in the late 1990s. Even then it was fully aware of the impacts that climatic changes were likely to cause.

In September 1999, Chamling is reported to have said, “The water in the Teesta is flowing at an all-time low.” He also noted that the Zemu glacier, the largest in the eastern Himalayas, had receded by up to 4 km. “We have had the warmest winter in living memory. These are all indications of things going wrong.”

Chamling, one of India’s longest-serving chief ministers who ran the state for a quarter century, ignored his own warning.

In a meeting on October 18, the Sikkim Cabinet also decided to carry out a survey of other lakes in the higher reaches of the mountains in Sikkim to ascertain if any of them posed any threat.

The collapse of the Chungthang dam was the most important reason causing the flash flood. Ideally, water should have been released in a controlled fashion into the dame through sluice gates and stored there. But its collapse led to the accumulated water rushing down and sweeping away everything on the way. Interestingly, in reply to the SKM charge of substandard construction of the Chungthang dam of Teesta Urja Stage III, SDF has said that during the previous regime the lake used to be drained periodically but this practice has been suspended under the rule of the SKM government.

The caved in portion of NH 10 in Setijhora.

In north Sikkim, an abode of the Lepcha and the Bhutia communities, locals had opposed the setting up of large hydropower projects on river Teesta, partly because of the dangers they pose and partly out of religious considerations. In Mun and Bongthing belief, the traditional religion of the Lepcha community, mountains and rivers are worshipped and are not to be disturbed by activities such as the construction of dams.

The flash flood has now made it difficult for the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) to set up the proposed Teesta IV project in Dzongu, the Lepcha reserve. The project has already been stalled because of objections from the local community. Chairman of Gorkhaland Territorial Administration in Darjeeling Anit Thapa has warned that he will not allow Teesta Low Dam III and IV, located in West Bengal, to resume generation till they build a guard wall on the slopes of river Teesta.

Tourism washed away

Tourism, the backbone of the economy of Sikkim, has been a big casualty.

Reports from west Sikkim, far off from the course of river Teesta, say the famous tourist destination of Pelling looks deserted; with no tourist in sight. The Khangchendzonga waterfall, one of the most popular destinations among domestic tourists and the most frequented sightseeing place near Pelling, remains empty and deserted these days. Usually, on an average more than 100 tourist vehicles frequent the waterfall daily. After the flood, the tourists have gone missing.

“Only a few locals stop by the sight nowadays,” Kiran Rai, a local youth who runs an eatery at the waterfall, told The Federal. Around 15 small eateries and shops set up in the vicinity of the waterfall have remained closed. Most people from the nearby village of Lungsugoan rely for livelihood on tourism.

Hoteliers in Gangtok have been hit hard.

Tourists after rescue from north Sikkim by an Indian Air Force helicopter.

“Most bookings to Gangtok and other tourist destinations in Sikkim have been cancelled,” proprietor of Kolkata-based West Bengal Adventure and Mountaineering Federation Chandra Nath Gupta told The Federal.

“My hotelier friend in Gangtok is telling me there is no water in his hotel. All the staff have taken leave and left for their villages. With no road connection, no power and no water, the busy tourism season during the pujas is lost.” Gutpa, who also organises tours, is not hopeful that the tourism scene in Sikkim will look up before Christmas.

By the time tourists return, Sikkim’s wounds may have healed but the scars will stay to remind everyone what recklessly implemented projects in the name of development can do.