- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

Why restoring Kannada classic Samskara would help preserve a landmark in Indian cinema

Based on the eponymous novella by UR Ananthamurthy, Pattabhirama Reddy's 113-minute classic introduced a starkly different cinematic language to Kannada cinema, rooted in literary depth, philosophical inquiry and social realism. The 1970 film is being restored by the Film Heritage Foundation.

Before Samskara — the Kannada classic produced and directed by Pattabhirama Reddy — was released in 1970, it had stirred a fair bit of controversy for its “explicit content”. There were protests by the Brahmin community and talk of the censor board not allowing its screening. However, the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal, after watching Samskara, decided against a ban, allowing...

Before Samskara — the Kannada classic produced and directed by Pattabhirama Reddy — was released in 1970, it had stirred a fair bit of controversy for its “explicit content”. There were protests by the Brahmin community and talk of the censor board not allowing its screening. However, the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal, after watching Samskara, decided against a ban, allowing its public screening.

And history was made!

The film went on to win the President’s Gold Medal for the Best Feature Film of 1970; interestingly, Pratidwandi, a film by acclaimed Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who was conferred an Academy Honorary Award in 1991, had been one of the contenders for the honour that year. Samskara was also screened at multiple international film festivals, including the one at Locarno (Switzerland), securing an award there. Now, the Film Heritage Foundation is restoring the Kannada classic, still considered a landmark in the history of Indian cinema.

Based on the eponymous novella by UR Ananthamurthy, Pattabhirama’s 113-minute film revolves around a small Brahmin agrahara (a village where Brahmins are in the majority), which is thrown into turmoil after the death of Naranappa, a Brahmin known for his defiance of caste rules and unorthodox lifestyle. Naranappa’s unconventional ways had earned him the wrath of the agrahara’s conservative Brahmins. After his death, the Brahmin elders of the village are unable to decide whether to give him a traditional Brahmin cremation or treat him as an outcast. Until the problem is resolved, neither they nor their immediate families may eat, as per Brahmin traditions. The film offered an intriguing glimpse into the lives and issues surrounding the orthodox community.

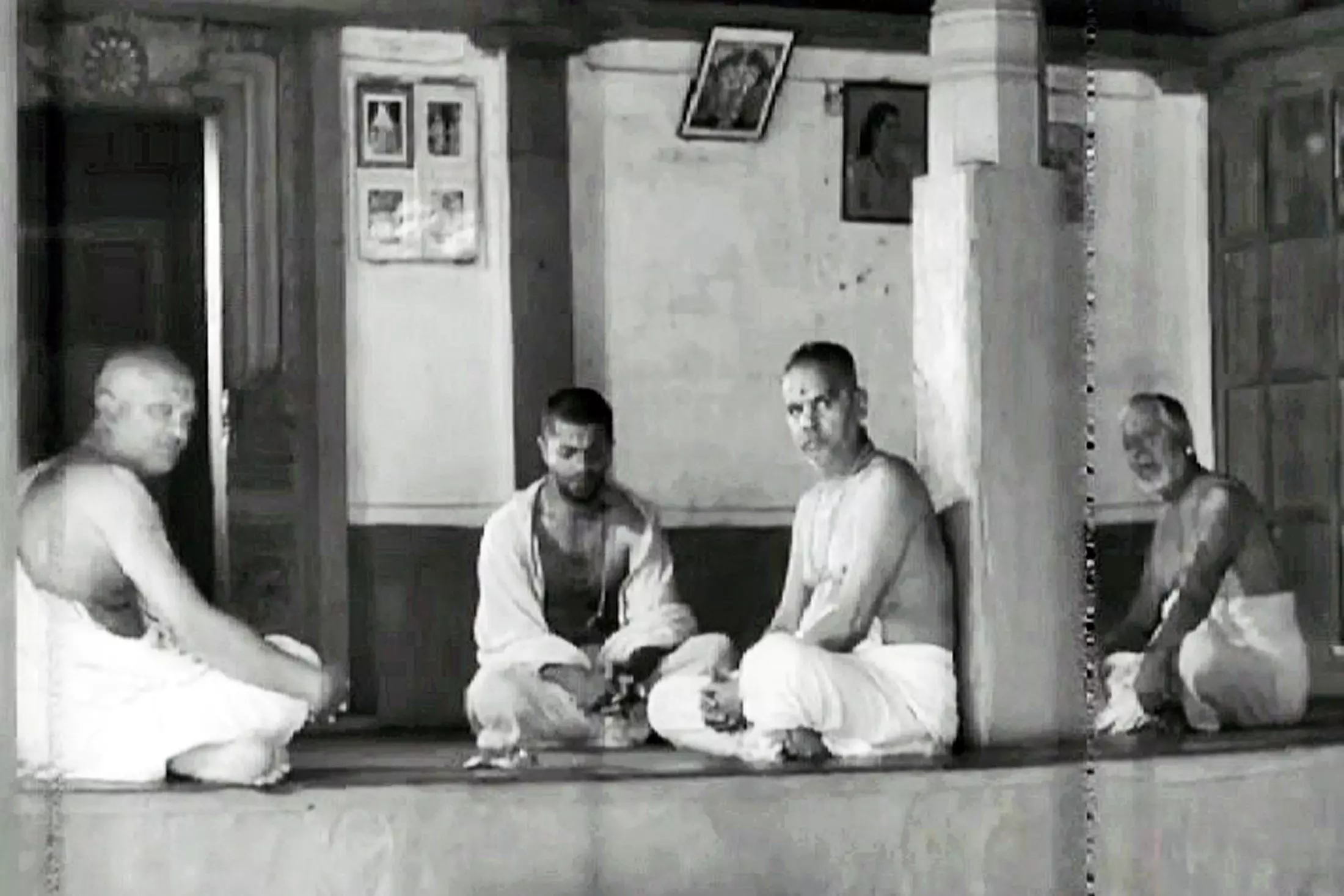

A scene from Samskara. Photo: By Special Arrangement

“Instead of a direct and possibly preachy assault on casteism, Samskara used an oblique form of attack,” explained renowned film critic and writer MK Raghavendra. “This eventually turned tragic, but there was a dark humour to it too; in a way, the Brahmins, intent on preserving their so-called Brahminism, pay no heed to what is surely approaching disaster. Or how their religion is easily set aside by more worldly concerns.”

Samskara’s writer, Ananthamurthy, had been a close friend of Pattabhirama because of their common acquaintances. While Ananthamurthy had been associated with socialist political leader Shantaveri Gopala Gowda — an ardent follower of freedom fighter and socialist politician Ram Manohar Lohia — Pattabhirama was closely associated with Lohia. It is said it was Lohia who impressed upon Gowda to ask Pattabhirama to make a film on Ananthamurthy’s novel.

Recalling how Samskara came to be filmed, Ananthamurthy, after the release of the film, wrote, “The year was 1965. While in Oxford, my tutor, Malcolm Bradbury, suggested I should write about my experience of centuries co-existing in India. That started me on writing Samskara in Kannada. For me, it was an act of self-discovery. Meanwhile, in India, Girish Karnad [the late actor, director and playwright, who played one of the protagonists in Samskara] had read the manuscript. He and Pattabhirama Reddy, along with a visiting Australian cameraman, Tom Cowan, had prepared a shot-by-shot script of it. I returned to India to find Karnad and others with shaven heads and tufts, ready to shoot and act in this film...”.

He added: “Film is not my medium and perhaps Pattabhi and Girish are justified in the changes they made. Yet I insist that my novel says something different, something more abstract… Pattabhi and Snehalatha [actor and Pattabhirama Reddy’s wife] made my novel their own and because they made it, sharing as they did a common heritage with me, in our radical anti-caste political tradition, the film was not an artistic venture, but a committed political act. The two were never separate in our minds.”

Also read: Why the death of a bird in his rehearsal space made theatre personality Prasanna give up direction

Samskara introduced a starkly different cinematic language to Kannada cinema, rooted in literary depth, philosophical inquiry and social realism. Through its bold exploration of caste, rituals, puritanism, hypocrisy and the fragility of moral authority, the film challenged deeply-embedded social structures. Its austere visual style and naturalistic performances aligned with the ‘new wave’ cinema taking root in India and the sensibilities of stalwart filmmakers like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak, who were similarly experimenting with the craft in Bengali.

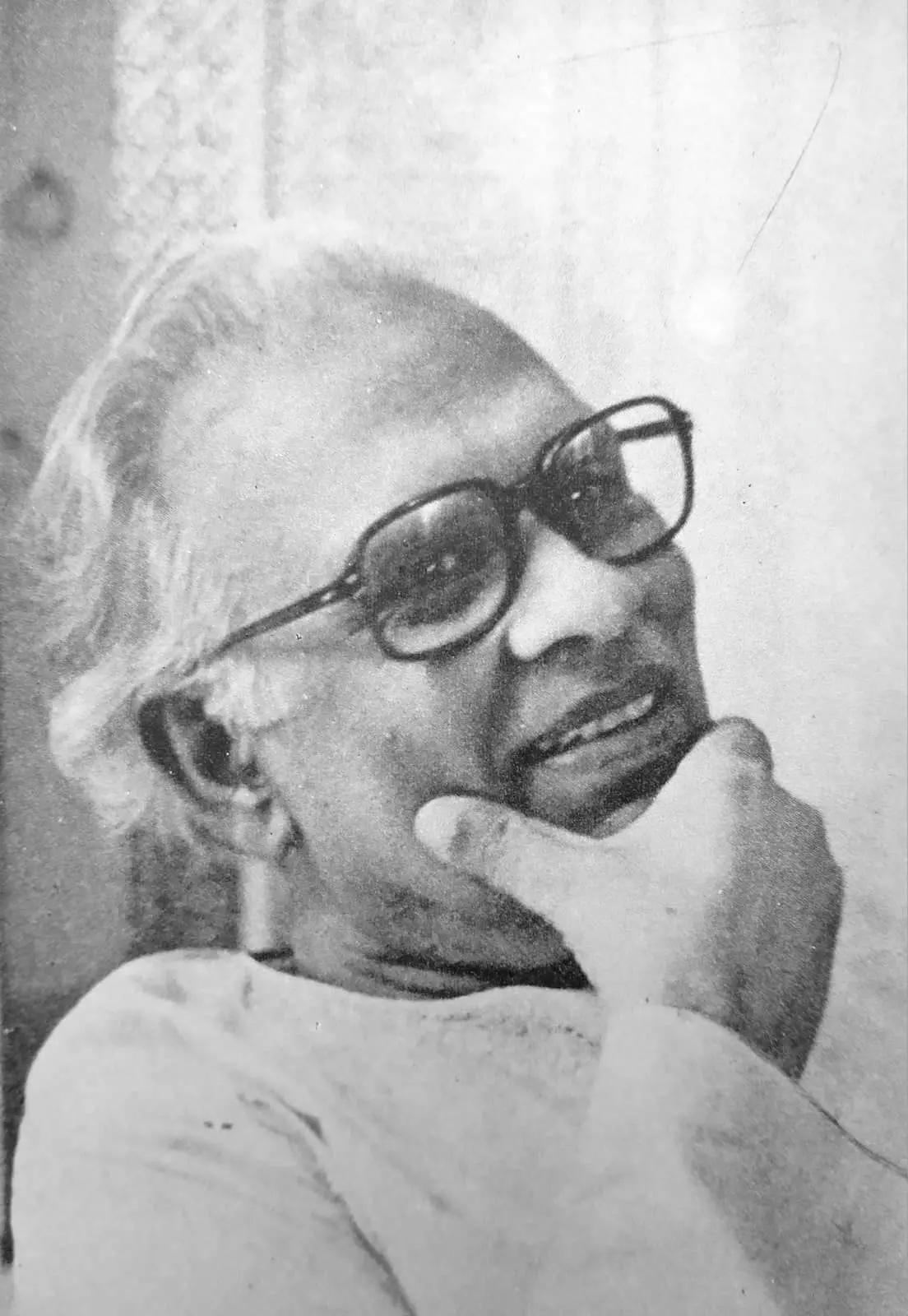

Samskara director Pattabhirama Reddy. Photo: By Special Arrangement

Pattabhirama’s film proved that regional cinema could be both artistically rigorous and socially provocative. In a way, it became a catalyst for Kannada new wave cinema and contributed significantly to the broader movement of parallel cinema across India, influencing generations of filmmakers, who sought to craft meaningful, realistic and intellectually-challenging cinema.

“Samskara continued to haunt me for years and I always wanted to explore and dig deeper into the film,” Nandana Reddy, Pattabhirama’s daughter, who made the documentary ‘Revisiting Samskara’ with colleague Aswhathi Rajakrishnan in 2019, to celebrate Pattabhirama’s birth centenary and 50 years of Samskara (in 2020), told The Federal.

She added: “My colleague and I took a ride to Sringeri via Vaikuntapura [in Karnataka], where the film was shot. Walking into the village felt like walking into the frames of ‘Samskara’. I reached out to Tom [Cowan], who later came down to India and that is how the documentary came about.”

According to Rajakrishnan, the documentary “recounts the experience of the cast and crew revisiting the same locations”.

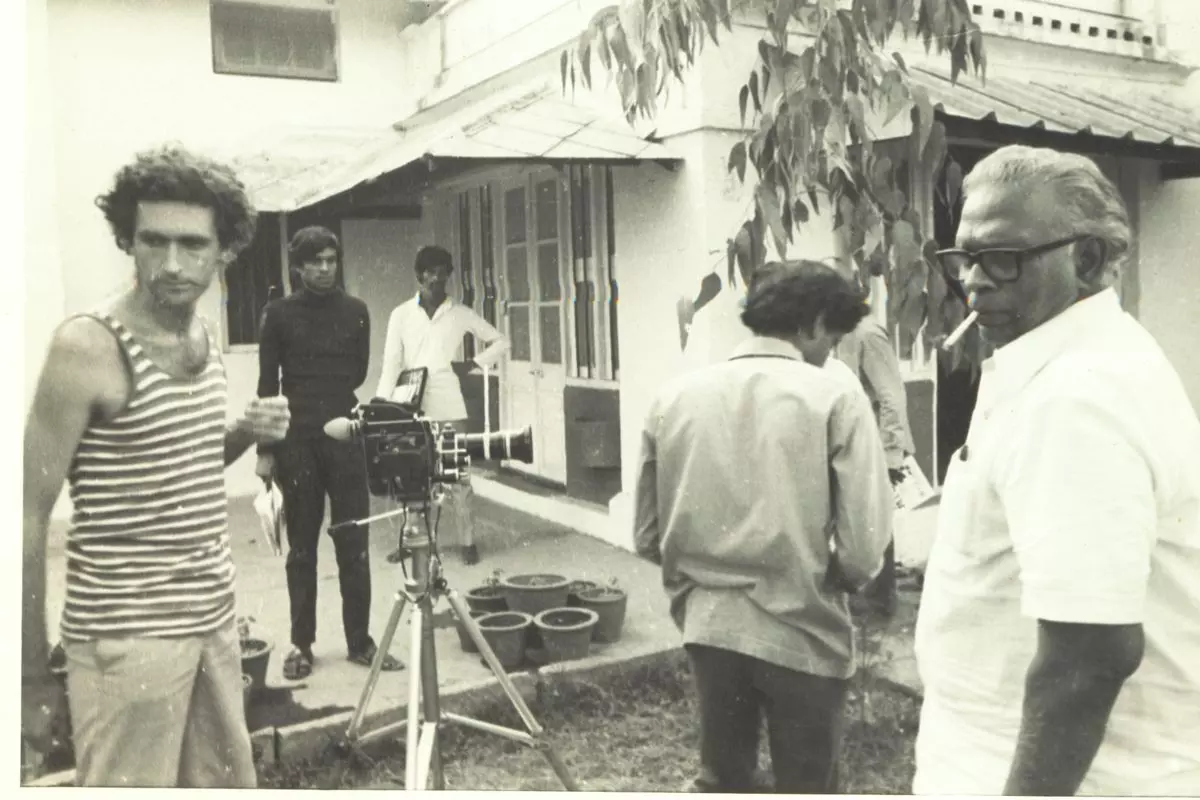

Shooting for Samskara. Photo: By Special Arrangement

For Cowan, who had been just 25 years old at the time of the making of Samskara, returning for the documentary jogged his memory of the time. “We had to shoot 900 shots in 30 days in the beginning of the ’70s. That is 30 shots per day. Each of them was meticulously shot and I think this was the great strength of the film,” the veteran cinematographer had said in 2019.

Also read: Why ongoing Kannada Sahitya Parishat row reflects a deeper decline in century-old institution

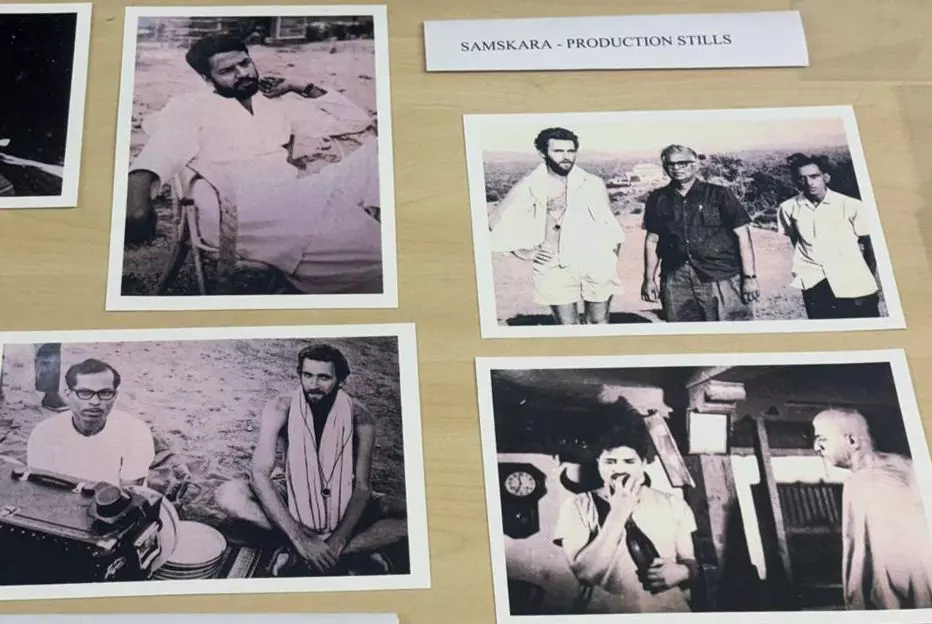

The evidence of Samskara’s continuing relevance and importance to Kannada and Indian cinema can be gauged from the fact that last month in Bengaluru, Max Mueller Bhavan, in collaboration with Arsenal — Institute for Film and Video Art, Berlin, organised a screening of the film. A panel discussion held as part of the event saw Nandana, Pattabhirama’s son, Konark and Arsenal Institute’s Markus Ruff talk of the need for restoring the film.

According to actor, director and artistic director of Infinite Souls/Little Jasmine Theatre Project, Kirtana Kumar, who is also Pattabhirama’s daughter-in-law, it was Konark who had first reached out to Shivendra Singh Dungarpur of Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) about Samskara’s restoration.

The Pattabhirama classic is not the FHF’s first brush with restoring a Kannada film.

Earlier, FHF, in collaboration with the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, founded by Martin Scorsese, had restored Ghatashraddha, the 1977 Kannada classic directed by Girish Kasaravalli, also based on a story written by Ananthamurthy. Also considered a landmark of Indian parallel cinema and a foundational film in the history of Kannada cinema, the restored Ghatashraddha saw its world premiere at the 81st Venice International Film Festival last year, in the Venice Classic Section.

An expert works on restoring a film. Photo: By Special Arrangement

Talking to The Federal at the time of the screening, Kasaravalli had lamented that many of the earlier films “were shot on 16 mm/35 mm film stock, which is highly susceptible to fungus, shrinkage, colour fading and emulsion fading due to poor storage in non-controlled humidity and heat. Some negatives remained with producers, others were untraceable for years”.

The earlier prints of Ghatashraddha too had “acid-related issues. Usable prints were available, but not of preservation grade”, he said.

According to a 2021 report prepared by a committee of experts on the state of Kannada classics, many of the prints were “in an irredeemable state”. The report added that “of the 5000 plus films made in nine decades of Kannada cinema, as many as 3500 have disappeared without a trace”.

Also read: Why NSD fee for acting course in Mumbai has raised concerns of the institute serving the elite

The film restoration process is an elaborate and expensive one.

“It involves specialised techniques, skilled professionals and advanced technology. Old films often suffer from issues such as shrinkage, vinegar syndrome, fungus, and physical damage, which require expert manual repair and careful handling,” said a senior technician at the National Film Archives of India (NFAI).

He added: “The process begins with the acquisition and identification of film elements such as camera negatives, prints and soundtracks and each element is inspected for shrinkage, tears, fungus, vinegar syndrome and other forms of deterioration. Films should be carefully cleaned using manual or ultrasonic methods to remove dust, dirt and mould. Damaged portions such as broken perforations, torn edges and weak splices are repaired. For long-term accessibility, preservation also involves digital and photochemical copying.”

While Dungarpur, in a communication to The Federal, confirmed that Samskara was being restored, he did not divulge details on the process, saying only that it was “not yet ready for screening”.

In his memoir, This Life At Play, Karnad had recalled how renowned poet and scholar AK Ramanujan, after watching the rushes of Samsakara, had certified the film to be “good, a sensitive perception of the novel by UR Ananthamurthy”. It had also been praised by Mrinal Sen for its artistic excellence and noted theatre practitioner Ebrahim Alkazi had sent a telegram to Karnad, praising Pattabhirama’s direction and Karnad’s acting, the Samsakara director had once shared.

Samskara production stills on display at Max Mueller Bhava, Bengaluru, during last months screening and panel discussion. Photo: By Special Arrangement

“The content of the film is courageous enough; its form even braver,” noted Booker-prize-winning Welsh novelist Bernice Rubens. “There are no stars, and it was shot wholly on location. It has no need to depend on elaborate studio sets or a floral music score, which are usually last resorts desperately engaged to camouflage a paucity of imagination. Samskara is a rich film that can only leave the spectators deeply moved.”

Also read: Samudaya at 50: Why Karnataka’s theatre collective must reinvent to stay relevant

In a review published in The Guardian on January 5, 1973, journalist Darryl d’Monte had written that Samskara was testimony to the quality of movies which ushered in a new era of filmmaking in Kannada. “The film is a startling indictment of caste and priesthood, two things that traditional India holds most sacred. Pattabhirama Reddy, the director, condemns the malignancy of caste-ridden village society by constantly intercutting throughout the film, to rats writhing their last in a plague epidemic that simultaneously strikes the Mysore village in which the action is set. Not surprisingly, the Mysore government tried to ban the film.”

French writer and film producer Serge Broomberg had once likened the search for a film to a treasure hunt. “You never know what treasure you will find. You want to go for more. You know there are more treasures to be found out there,” he said.

Restoring Samskara could be termed rediscovering one such treasure of Kannada cinema.