- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Pungent platter: How far is Indian-grown hing from your kitchen?

The pungent asafoetida—commonly known as hing/hingu in most Indian languages, and peringayam in Tamil—is a ubiquitous spice, an essential ingredient found in almost every Indian kitchen. It has also remained integral to the traditional Indian medicine system of Ayurveda since time immemorial, with the polyherbal formula Hingwashtak Churna being highly popular that continues to be used as...

The pungent asafoetida—commonly known as hing/hingu in most Indian languages, and peringayam in Tamil—is a ubiquitous spice, an essential ingredient found in almost every Indian kitchen. It has also remained integral to the traditional Indian medicine system of Ayurveda since time immemorial, with the polyherbal formula Hingwashtak Churna being highly popular that continues to be used as a household remedy for common gastric ailments. It’s not a surprise, then, that India accounts for almost 40% of the world consumption of asafoetida, according to rough estimates.

What is truly surprising, however, is that India does not produce any asafoetida at all. Since ancient times, this vital spice has been completely imported by India with Afghanistan providing almost 90% of that requirement, and the rest being supplied by Uzbekistan (8%) and Iran (2%), according to publicly available trade figures of 2023. That amounts to annual import of asafoetida worth 1500 tonnes valued at Rs 940 crore.

CSIR-IHBT director Dr Sudesh Kumar Yadav (centre) at the Seed Production Centre at CSIR-IHBT Palampur, Himachal Pradesh.

This scenario, however, is set to change, with an initiative undertaken by CSIR-IHBT (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research – Institute of Himalayan Bioresource Technology), Palampur, that has introduced asafoetida cultivation in the cold desert conditions of five districts of Himachal Pradesh. The first yield is likely to be harvested in a year or two, with the promise of saving a substantial amount in foreign exchange that the country currently spends in buying this spice vital to all varieties of Indian cuisines, and to alternate indigenous medicine systems such as Ayurveda and Unani.

Why is asafoetida not cultivated in India?

Asafoetida is the dried latex (gum oleoresin) exuded by the rhizome or tap root of Ferula assa-foetida, a perennial herb of the Umbelliferae family (to which also belong celery, carrot, parsley, cumin, caraway, coriander, etc.). Its pungent smell is its most prominent characteristic; ‘ferula’ in Latin means ‘carrier’, ‘asa’ is a Latinized form of Persian that means ‘resin’, and ‘foetidus’ is Latin for ‘smelling, fetid’. Its strong smell gave it the rather uncharitable old English acronym of ‘devil’s dung’. The strong, pungent odour of the resin is likened to sulphur or garlic, which lends a characteristic savoury flavour when cooked.

Ferula assa-foetida is endemic to Afghanistan, Central Asia and Iran, as it requires a cold climate, and arid but sunny conditions to grow. It takes nearly five years to produce the oleoresin in its roots. Close to 130 species of Ferula are found globally. Of these, Ferula jaeschkeana and Ferula narthex are reported from the western Himalayas. The former is found in the Chamba and Lahaul regions of Himachal Pradesh, while the latter has been reported from Kashmir and Ladakh. However, asafoetida of commercial importance is obtained from Ferula assa-foetida, which is not reported from India.

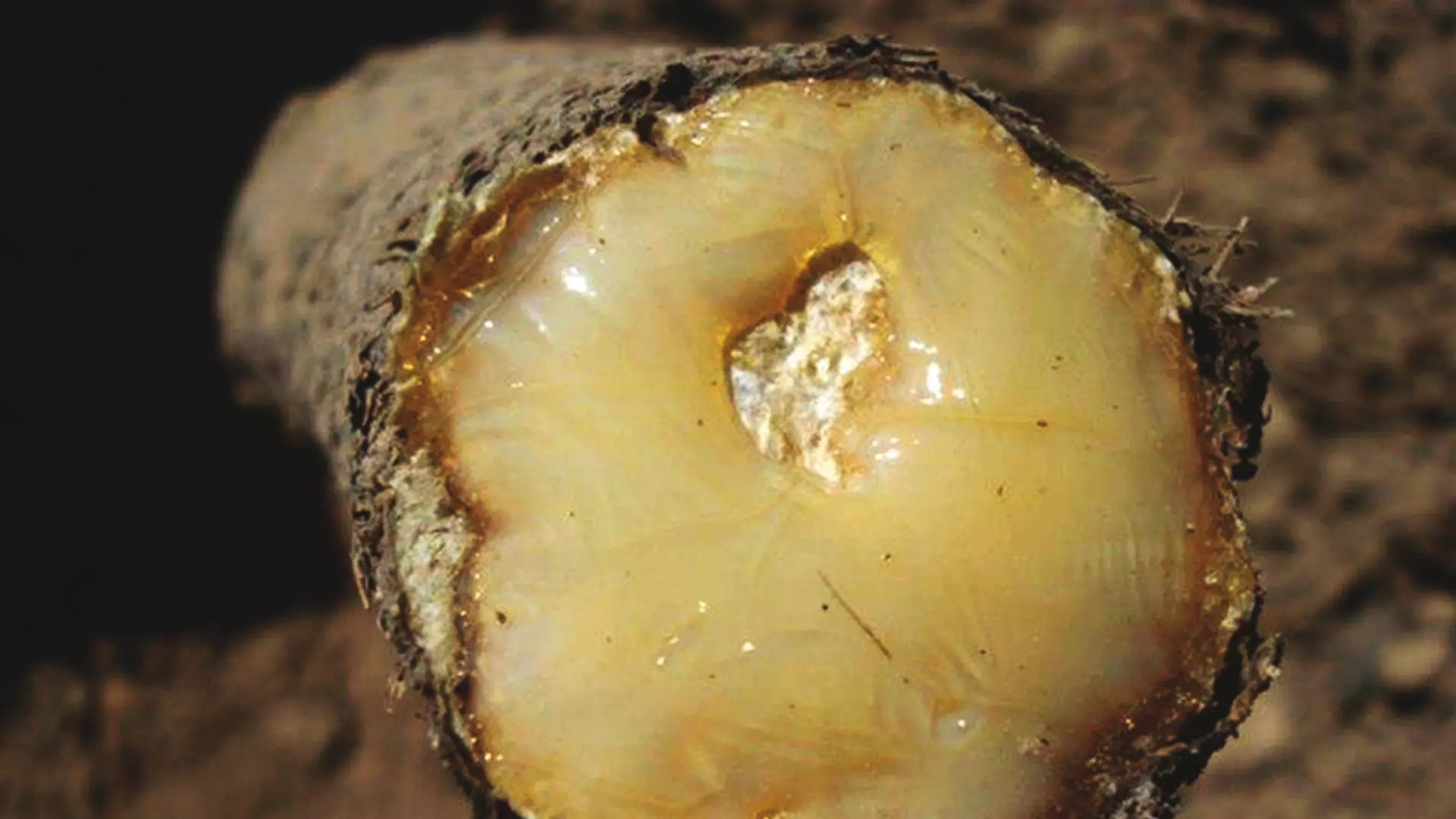

The root of the plant Ferula assa-foetida.

The Ferula plants possess large taproots or carrot-shaped roots, approx. 12.5 – 15 cm in diameter. These plants flower usually in March-April. When the upper part of the living rhizome root is exposed, the stem is cut off near the crown, and the milky resin is extracted. Repeated slicing of the root allows successive collection of the resin as it continues to be exuded for up to three months since the first cut. The resin is dried into a solid mass, which is further processed into a powder or sold as a solid resin. The resin comes in two forms, viz., hing kabuli sufaid (milky white asafoetida) and hing lal (red asafoetida). The white or pale variety is water soluble, whereas the dark variety is oil soluble.

In India, imported asafoetida resin is ‘stabilised’ with an edible substance, such as wheat or rice flour, and then formed into lumps, granules, and powders. The additives aid in regulating the concentration of asafoetida based on its intended use. The UAE, the US, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Malaysia are top markets for value-added asafoetida exported from India.

Cultivating asafoetida in India

The CSIR-IHBT project began with the planting of seedings in 2020 under the leadership of then director Dr Sanjay Kumar. IHBT introduced 66 accessions of Ferula assa-foetida seeds from Iran and Afghanistan through the ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (ICAR-NBPGR), New Delhi. The seeds were raised at the Centre for High Altitude Biology (CeHAB), Ribling, in the Lahaul-Spiti district of Himachal Pradesh, under the supervision of NBPGR. An important part of this process was the need to authenticate the species introduced by the development of DNA-based genetic markers. DNA bar-coding was successfully done at CSIR-IHBT to authenticate the Ferula assa-foetida species introduced.

“The seed grown seedings of Ferula for yielding asafoetida were first planted in 2020 and hopefully, in a year or two, we will have the first yield. It is still in the experiment stage and things are going well, so we will have to see how things shape up in the next year or so,” says Dr Sudesh Kumar Yadav, Director, CSIR-IHBT, Palampur.

Dry temperate climate with an average rainfall of 100-250 mm, soil with 15-30% slope, and an altitude of 2000 m to 3500 m are considered suitable conditions for the growth and development of Ferula assa-foetida. Ecological niche modelling (ENM) was carried out for the identification of niche areas, and Lahaul & Spiti, Kinnaur, Mandi, Kullu and Chamba districts of Himachal Pradesh were expected to be suitable for its cultivation. Similarly, union territories of Ladakh, J&K and parts of Uttarakhand were also found suitable for the cultivation of asafoetida. “Geography is the main factor in the cultivation of asafoetida, which decides whether it will grow at a particular place,” adds Dr Yadav.

The initial characterisation findings indicate that the Ferula assa-foetida plant, when cultivated in Indian conditions, exhibits quality traits and chemical constituents that are at par with those known for the distinctive aroma characteristic of the spice.

After the project began, the government of Himachal Pradesh threw its weight behind CSIR-IHBT through its ‘Krishi Se Sampannat Yojana’ (‘Prosperity Through Agriculture’ scheme), and an MoU was signed between the two for the cultivation of asafoetida in the state.

The farmers of Himachal Pradesh are now taking up the cultivation of asafoetida to utilise vast expanses of wasteland in the cold desert conditions of the region. In the five shortlisted districts of Himachal Pradesh, asafoetida has been planted in an area covering about seven hectares. While more than a thousand farmers have been trained the cultivation of asafoetida, about 290 have already initiated the cultivation of the plant on their farms.

On an average, each plant is likely to produce 25 to 30 grams of asafoetida, which on a hectare of land translates to two-and-a-half quintals of the spice (a quintal = 100 kgs).

Challenges ahead

“While working on this project since 2020, CSIR-IHBT has been faced with a lot of opportunities as well as hurdles. We have crossed a majority of those hurdles, and we continue to carry out explorations with whatever information we have gathered so far,” shares Dr Yadav.

A major constraint is seed germination due to seed dormancy; generally, the rate of germination is 1-2% under normal conditions. This could lead to a scarcity of sufficient planting material, creating a significant obstacle in the widespread cultivation of the spice in India. Efforts were made at the institute to standardise seed germination through a series of experiments in the laboratory, and finally, seed germination of 60-70% was achieved for raising planting material of asafoetida. Germplasm resource centre and seed production centres were also established at Palampur to conserve the germplasm resources and produce indigenous asafoetida seeds.

Addressing this challenge requires innovative approaches, and one such method is in vitro mass propagation, which enables the rapid multiplication of planting material under controlled laboratory conditions. Recognising the importance of this technique, the institute has developed specialised tissue culture protocols tailored for the commercial-scale production of Ferula assa-foetida.

Asafoetida seeds. India is likely to have its own home-grown hing in just a couple of years.

“Besides asafoetida, CSIR-IHBT is carrying out several other experiments and projects, such as growing marigolds and tulips. The CSIR-IHBT now has India’s second tulip garden (the first is in Kashmir) and for the past two years we have been showcasing the flowers during February-March. With adequate R&D, we have succeeded in growing and multiplying the bulbs indigenously and the tulips that grow here are completely homegrown, unlike other places, where bulbs are imported from the Netherlands.”

While CSIR-IHBT continues to carry out a wide gamut of experiments—from the sharp asafoetida to fragrant marigolds, it is the former that is likely to prove a gamechanger in Indian agriculture, given the unequivocal importance of the oleoresin, not just for its taste-enhancing properties but also for its great pharmacological application in traditional medicine for healing a variety of ailments.