- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Northeast in Bengaluru: Putting 2012, Kuki-Meitei differences aside, a fight for survival goes on

Back home in Manipur, they may be gunning for each other, but at 20 Feet High, a vibrant eatery on Bengaluru’s Church Street in the city centre, almost all waiters from different ethnic groups of Manipur — Kukis, Meiteis and Nagas, work together. When asked where they hail from, they all say Manipur, adding in the same breath, a state in the Northeast.Locals know Manipur well because...

Back home in Manipur, they may be gunning for each other, but at 20 Feet High, a vibrant eatery on Bengaluru’s Church Street in the city centre, almost all waiters from different ethnic groups of Manipur — Kukis, Meiteis and Nagas, work together. When asked where they hail from, they all say Manipur, adding in the same breath, a state in the Northeast.

Locals know Manipur well because of horrific videos of violence emerging from the state over the past 20 months or so. But they hardly ask the waiters where they are from. “It seems they know we are from Northeast or Nepal but so long as they are served well, the customers are friendly,” says Michael from Churachandpur in the Kuki-dominated southern Manipur. “They have gotten used to us.”

The violence back home has created some distance between those from Manipur but it has not affected the working relationship. Inquiries revealed the waiters stuck to their ethnic mates while choosing Paying Guest (PG) accommodations but if employers offered living space for all in one place, they have stayed together.

“We are all here to earn our bread and butter. What is happening back home is painful but we cannot let that impact our work here and fight with are fellow workers just because we come from different ethnicities. In Bengaluru, we are all identified as one – people from Northeast,” Michael says.

Sticking together is a necessity and there is no option for the Northeasterners, who could not complete higher studies, other than working in Bengaluru.

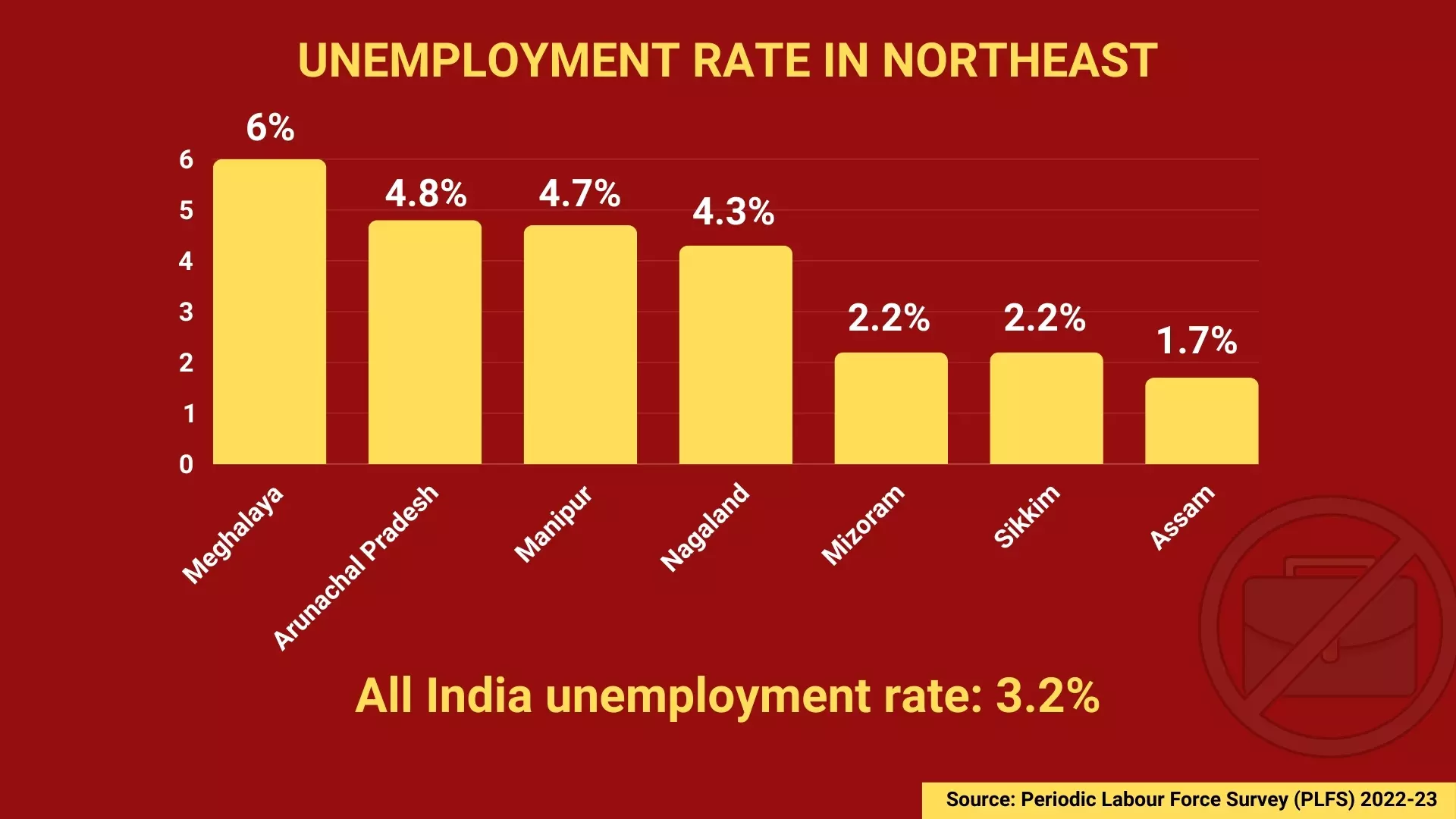

Most Northeastern states like Assam and Manipur have high youth employment rates. According to Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2022-23 data, while the national employment rate is 3.2%, in Meghalaya it is 6%. In Arunachal Pradesh, unemployment rate is 4.8%, while Manipur stands at 4.7%, and Nagaland at 4.3%. The situation is somewhat better in Mizoram with 2.2% unemployment, in Sikkim with 2.2% and Assam at 1.7%.

The Northeast has historically been neglected in terms of investment in education and training. This has led to a shortage of skilled workers in the region. There is also a mismatch between skills and jobs, which makes it hard to find employment.

In the northeast, only one state university, Gauhati University, is in the top 100 – in the 88th position. Even with the inclusion of central universities, none comes even close to the top 50 ranks.

Among the eight northeastern states, there are only four medical colleges and only one college for architecture and fisheries.

The only jobs back home are in the government sector, but they too are scarce. “Hefty bribes have to be paid to powerful politicians and bureaucrats for these jobs, so coming to Bengaluru and getting a waiter’s job through a reference from an ethnic cousin is much easier,” says Dipak Basumatary from Assam's Kokrajhar district. He landed his present job at the local restaurant through a fellow Bodo tribesman working there as a supervisor.

Dipak says the youth from Northeast have two job options he describes as realistic — army and other Central paramilitary forces or hospitality jobs in cities like Bengaluru. “If you are a computer engineer, you would get jobs anywhere. But for someone like me, it is either the forces or the hotel or restaurant jobs here.”

The eateries are thronged by the youth from Northeast as if 2012 never happened.

During the 2012 scare when Northeasterners left Bengaluru in hordes after threats from local Muslims angry over attacks on their co-religionists in Assam, employers tried putting their workers from the region in one secure place close to the place of work.

But things quickly spiraled out of control following the stabbing of 22-year-old Tenzin Dhargiyial, a diploma student of Kushalnagar College. Tenzin, a Tibetan was reportedly stabbed in Mysore after being mistaken to a Northeasterner. The threatening bulk SMSes that sparked the 2012 exodus of Northeasterners still haunt those from the region working in Bengaluru, which is why all those The Federal approached for the story spoke on the condition that they remain anonymous.

At the peak of the scare, nearly 30,000 Northeasterners had fled Bengaluru. Of Bengaluru's 10 million residents, 2,50,000 are believed to be from the northeastern States. And most of those, who had fled, seem to have returned.

Michael* says there are no jobs back home and the situation in Manipur is “really bad”. “I cannot think of working in the state capital Imphal because I am a Kuki. Here no one is bothered,” he says.

“The working conditions here are good, no hassles in work place or with landlords.”

A few kilometres away, in another swanky restaurant named Stories, Lillian* meets you at the reservation counter, checking the booking details. She is also from Churachandpur. When convinced the author knows her town well enough, Lillian opens up. The working conditions are good, women feel safe here, locals don’t grill Northeasterners just because they look different — in short, it is far better to be in Bengaluru and working than being stuck back home in a violent conflict. “We can’t ask for heavens but our employers value our service,” she says.

For those like Michael and Lillian, fluency in spoken English, easy manners and a pleasant disposition make them ideal for the low-end jobs in the hospitality trade.

But why Bengaluru? Because for the same job back home, salary is much lower.

Binita Barua was offered Rs 15,000 for a big hotel in Guwahati and a bit more for one in Kolkata after she graduated in hotel management. In Bengaluru's ITC Gardenia, she earns more than double that much after barely two years of service. “Some of my college seniors have got opening in the Middle East. Their life is made.”

At ‘Liverpool’ hotel on the Outer Ring Road near Marathahalli, almost all the restaurant waiters and housekeeping staff are from Northeastern states like Assam and Tripura. “I won't get as much money as I get here. Since food and stay is taken care off, I am fine,” says Abdul*, who hails from Karimganj in southern Assam.

The story is the same in many other restaurants. The waiter who served our table in ‘Stories’ is Nazeem, a Muslim of Bengali origin from Assam's Nagaon district. For him, working in the Bengaluru restaurant is rewarding because upmarket customers frequenting ‘Stories’ leave behind generous tips if happy with advice on choice of food and drinks.

Would he plan a restaurant of his own back home some day? “I don’t think something like this will work in my hometown. After all, Bangalore (he prefers the city's old name) is Bangalore. The world is here.”

(Names have been changed because after the 2012 scare, none want to be identified by name.)