- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

No posters, door-to-door campaigns: How Mizoram adds sanity to poll electioneering

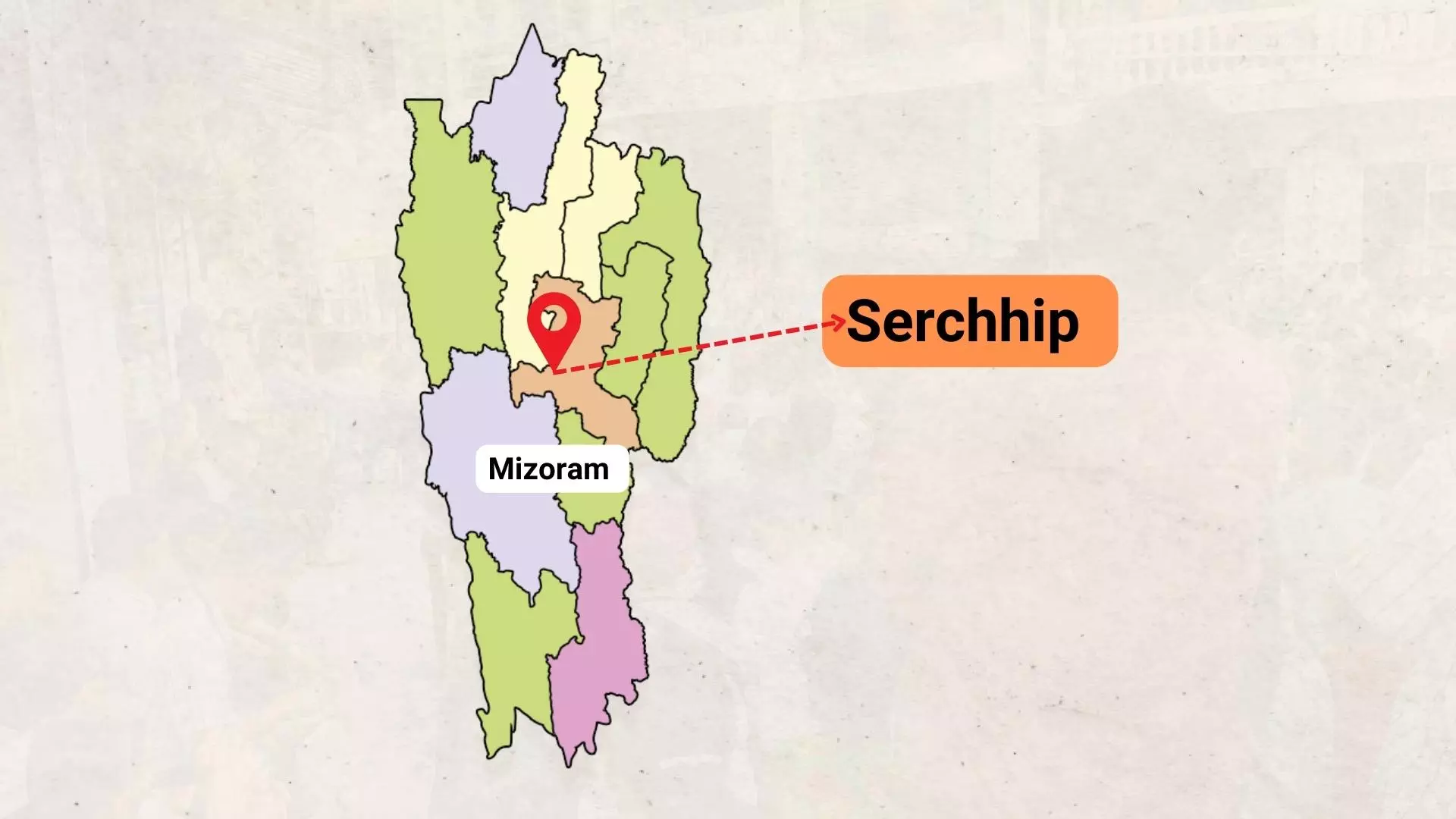

About 112 kilometres away from Mizoram’s capital Aizawl, Serchhip is as quiet as it is quaint. On October 27, this quiet region with a population of about 30,000 saw all roads turning to a narrow lane, flanked by buildings on either side, where a modest stage had been erected for what is called a ‘common platform’, unique to the Northeastern state.People, among them supporters of all...

About 112 kilometres away from Mizoram’s capital Aizawl, Serchhip is as quiet as it is quaint. On October 27, this quiet region with a population of about 30,000 saw all roads turning to a narrow lane, flanked by buildings on either side, where a modest stage had been erected for what is called a ‘common platform’, unique to the Northeastern state.

People, among them supporters of all the parties and candidates in the fray, started gathering in front of the stage with no sense of animated rivalries that are integral to electoral battles in other parts of the country, often leading to violence.

As the contestants of the Serchhip seat took their seats exchanging pleasantries, a similar camaraderie was replicated by their supporters who shared jokes in between holding general conversations.

Standing out

In the high-decibel electoral battle of five states — Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Telangana and Mizoram — the campaign in Serchhip stands out holding a mirror to campaigns running on the fuel of money and muscle power, with communal undertones, personal barbs and below-the-belt attacks.

People attend a 'common platform' in Mizoram. Mizoram stands as an aberration to high-pitched campaigns marked by cacophonies of tall promises, riots of posters, hoardings and billboards.

In an election being seen as the semi-final to the 2024 national elections, Mizoram is easy to miss lying in the far northeastern part of India with just one Lok Sabha seat in its kitty.

Nevertheless, Mizoram stands as an aberration to high-pitched campaigns marked by cacophonies of tall promises, riots of posters, hoardings and billboards.

The hullabaloo that has been synonymous with elections in the rest of the country is conspicuous by its complete absence even in the constituencies in the hilly state that are bracing for a high-stakes contest.

One such battle is awaited in the Serchhip assembly constituency—one of the three assembly segments of the district with the same name.

In Mizo, Serchhip means citrus-on-top. The name was derived from citrus trees that grew abundantly on the hilltop where a legendary Mizo chief Lallula established a settlement centuries ago.

Most citrus trees on the hilltop have now been replaced by office and residential buildings that have come up as a natural progression of the place that over the years have metamorphosed into an important nerve centre of the state.

Perched at a height of 2,913 ft above sea level some 112 kilometres south-east of state capital Aizawl, Serchhip still boasts of many feathers in its hat including that of being the most literate district in the country with a male literacy of about 98.44% and female literacy rate of nearly 98.15%.

The scene at BJPs Mizoram headquarters. Only a few flags flutter on the premises but there are no posters or cut-outs. Photo: Zodin Sanga

This election season, the district is in the spotlight because of its Serchhip assembly seat, which has been a VIP seat for long.

Serchhip is democratically vibrant a fact reflected in how it had elected former chief minister Lal Thanhawla several times until handing him down a career-shattering defeat in 2018.

Absence of Lal Thanhawla from the state’s political scene this time, however, failed to take away the high-profile tag of the constituency.

Lalduhoma, the chief ministerial candidate of the Zoram People’s Movement (ZPM), billed as the dark-horse of this electoral battle, is seeking re-election from the seat.

His two main challengers are journalist-turned politician and ruling Mizo National Front (MNF) nominee J Malsawmzuala Vanchhawng and a veteran politician and Congress candidate R Vanlaltluanga. Also in the fray is K Vanlalruati of the BJP and two independents.

Low on noise, high on content

The status of the constituency notwithstanding, there is hardly any sign of the impending battle. One will have a tough time locating any poster, or cut-out of the candidates, or party flags. This is because all parties and candidates have entered into an agreement to strictly follow a set of dos and don'ts.

No, the Election Commission of India, has nothing to do with this.

An all-pervasive poll monitoring body of the state known as Mizoram People’s Forum (MPF), a church-controlled election watchdog, is responsible for limiting the poll splurge and maintaining electoral decorum.

All political parties and candidates enter into a written agreement with the forum ahead of the elections to abide by the codes of conduct.

As per these jointly agreed codes, no candidate or the party should spend exceed the electioneering expenditure limit stipulated by the ECI.

“Since hoisting of banners, flags and posters increase the election expenditure, the number of banners, flags and posters to be used are fixed according to the size of the local area,” reads a clause of the agreement.

Serchhip is democratically vibrant a fact reflected in how it had elected former chief minister Lal Thanhawla several times until handing him down a career-shattering defeat in 2018.

It allows a maximum of four banners, 50 flags and 30 posters in a constituency. Size of a banner, as per the guidelines, should not be more than 4x8 feet. In the case of posters, the size should not exceed 3x4 feet.

The size of the flag on a two-wheeler should not be more than 1x2 feet and 2x3 feet for a three and four-wheeler. Only one flag is allowed per vehicle. The height of the flag should not be more than three feet, as per the specifications.

Use of loudspeakers, horns or making of any noise that would disturb others are not allowed, as per the unanimously agreed guidelines. Any procession after declaration of election is also prohibited.

Public meetings by parties, even those addressed by their central leadership, are chaired by the MPF.

These dos and don’ts have been arrived at with an aim to make the election process cleaner, less expensive, free and fair.

“These guidelines are however not rigid or something imposed on the parties, or the candidates. They are worked out jointly with stakeholders after discussions. The guidelines are also changed as and when felt necessary,” Vanlalrema Vantawl, adviser to Mizoram People Forum, General Headquarters, told The Federal.

For instance, all stakeholders have decided to do away with the door-to-door campaigning from this year as some parties felt it provides room for “corrupt practices” besides being an “expensive and exhausting endeavour”, Vantawl explained.

With so many self-imposed campaign restrictions in place, MPF’s ‘common platform’ is the way for candidates to put their agenda before the public. MPF organises political campaigns at various levels — central, constituency and local — across the state in every election.

Here the candidates are allotted time slots to explain why they should be elected by the voters. The contestants are, however, not permitted to engage in a debate or a verbal match.

“We don't allow a debate at the MPF common platform, nor do we allow questions from the audience in order to avoid inappropriate questions and to false promises which cannot be delivered. This done in the interest of the candidate,” Vantawl explained.

But that does not prevent the candidates from highlighting the weaknesses of their rivals.

ZPM’s Lalduhoma is a resident of Aizawl West-I and so is in a way outsider to Serchhip. To underscore this, MNF candidate Vanchhawang was heard telling the voters from the common platform on October 27 about the pros of electing him, a “native of Serchhip constituency”.

Even in highlighting the drawbacks of other candidates, the line is never crossed. If it did, the forum “names and shames” them.

“If a party or a candidate violates the agreed terms we make it known to the voters by making an announcement through the public address system which is there in every locality,” the MPF spokesperson added.

Following the recent padyatra by Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, which is deemed as violation of the agreement, the state unit of the party publicly apologised for the lapses. If the violation is of serious nature such as breach of model code of conduct set by the ECI, then the forum files an FIR and lodges complaints with the commission.

The state unit of Mizoram publicly apologised for Rahul Gandhis padyatra. Photo: PTI

More than the preventive actions, the inherent sense of discipline among Mizos is behind the success of this unique template of Mizoram elections. This discipline is much like a way of life for ordinary Mizos and is not restricted to electoral campaigns.

It is this sense of discipline that prevents motorists in the state from jumping lanes or overtaking in traffic. It was the same discipline that made the joint platform at Serchhip to begin and end on the dot.

How it started

The template, which has now become a model for the rest of the country, came into being in the 2008 assembly elections.

“Elections in Mizoram had been by and large peaceful and bereft of much extravagance until 2003. There were many complaints of use of money and muscle power in the elections that year. It left the entire society, including politicians, shocked,” Vantawl recalled.

It was then that the need to introduce some checks and balances in the elections was felt and the MPF was formed in 2006 to supplement the ECI’s effort to make the elections a clean and fair exercise.

“The election process is still not as clean as we would like it to be. There are allegations of candidates trying to bribe voters,” said Emanuel Lalngaihawma, a young voter from Aizwal West-1 assembly constituency.

The scene at ruling MNF's office. Photo: Zodin Sanga

However, these allegations are insignificant in number as compared to the overall election scenario in other parts of the country.

“We have our limitations. We cannot keep a watch on every nook and cranny of the state. But we are constantly striving to make the elections a better democratic exercise. We have a plan to set up a research team to ensure proper implementation of poll promises made in the elections manifestos,” Vantawl added.