- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

Kisses and Cliffhangers: How women reshaped romance literature

Imagine the bustling Delhi Metro at 7 pm on a Friday, a microcosm of the capital city’s chaotic energy, where amidst the ebb and flow of commuters, a young woman finds solace in literature. With legs crossed and a novel in hand, she appears to be lost in the pages, oblivious to the cacophony of the mundane surrounding her. The occasional glance at the station signs is a necessity, to...

Imagine the bustling Delhi Metro at 7 pm on a Friday, a microcosm of the capital city’s chaotic energy, where amidst the ebb and flow of commuters, a young woman finds solace in literature. With legs crossed and a novel in hand, she appears to be lost in the pages, oblivious to the cacophony of the mundane surrounding her. The occasional glance at the station signs is a necessity, to reach home, but her attention seems to be tightly held by her current read: the latest offering from Colleen Hoover, the internet sensation, It Starts With Us (Simon and Shuster, 2023) a sequel to her New York Times bestselling book, It Ends With Us (Simon and Schuster, 2016).

One would like to believe that this scenario is quite unique — considering the times we live in, of short-form content on Instagram and OTT platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime, with their innate ability to draw us in — but it is not. Countless women (and men) find solace and joy in romance novels. From classics like Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind (Macmillan Publishers, 1936) to contemporary smash hits like EL James Fifty Shades of Grey (Vintage Books, 2011). But what draws people to romance? Is it an over-the-top declaration of love? The hope of finding a happy-ever-after in one’s own life? Or just a quick escape from reality? The genre’s popularity lies in its capacity to offer something for everyone, easily transcending time, location, and culture.

Ankita Misra, a Medicine Doctor at Bombay Hospital, finds "comfort in romance's ability to transport her to a world of happy endings and relatable struggles". For debut author, Swati Hegde, whose upcoming rom-com Match Me If You Can (Dell, 2024) is scheduled for publication in May, romance novels play a crucial role in shaping readers’ perceptions of healthy relationships and empowerment. She says, “Romance readers know that it’s not just about who buys you flowers or tells you they love you—it's about who stands by your side through the difficult moments and chooses you no matter what.”

But are romance novels only for women? Historically, yes. Without delving too deep into a history lesson, the genre has had a rather long journey of being dismissed and marginalised by literary circles and often viewed through the lens of the male gaze as lacking literary merit, depth, and nuance. How could a story about a man going to lengths to be with a woman who happens to be the love of his life make more of a ‘compelling’ and ‘important’ read as a man going to fight in a war? Think about it. It simply couldn’t. And so, romance was ‘frivolous’ and ‘feminine’.

With the rise of the Industrial Revolution, as the literacy rates grew, so did the cheap, mass-produced paperback novels. Renowned women writers like Charlotte Brontë, Jane Austen, and Daphne Du Maurier wrote books – about everyday lives, hopes and aspirations, struggles and shortcomings of female protagonists – which flooded the markets. However, the perception of women’s writings was predominantly for women audiences continued to dominate.

One must address the elephant in the room – how did romance go from being so critically viewed, apparently ‘lacking in substance’, and for women, to one of the most popular genres in the 21st century?

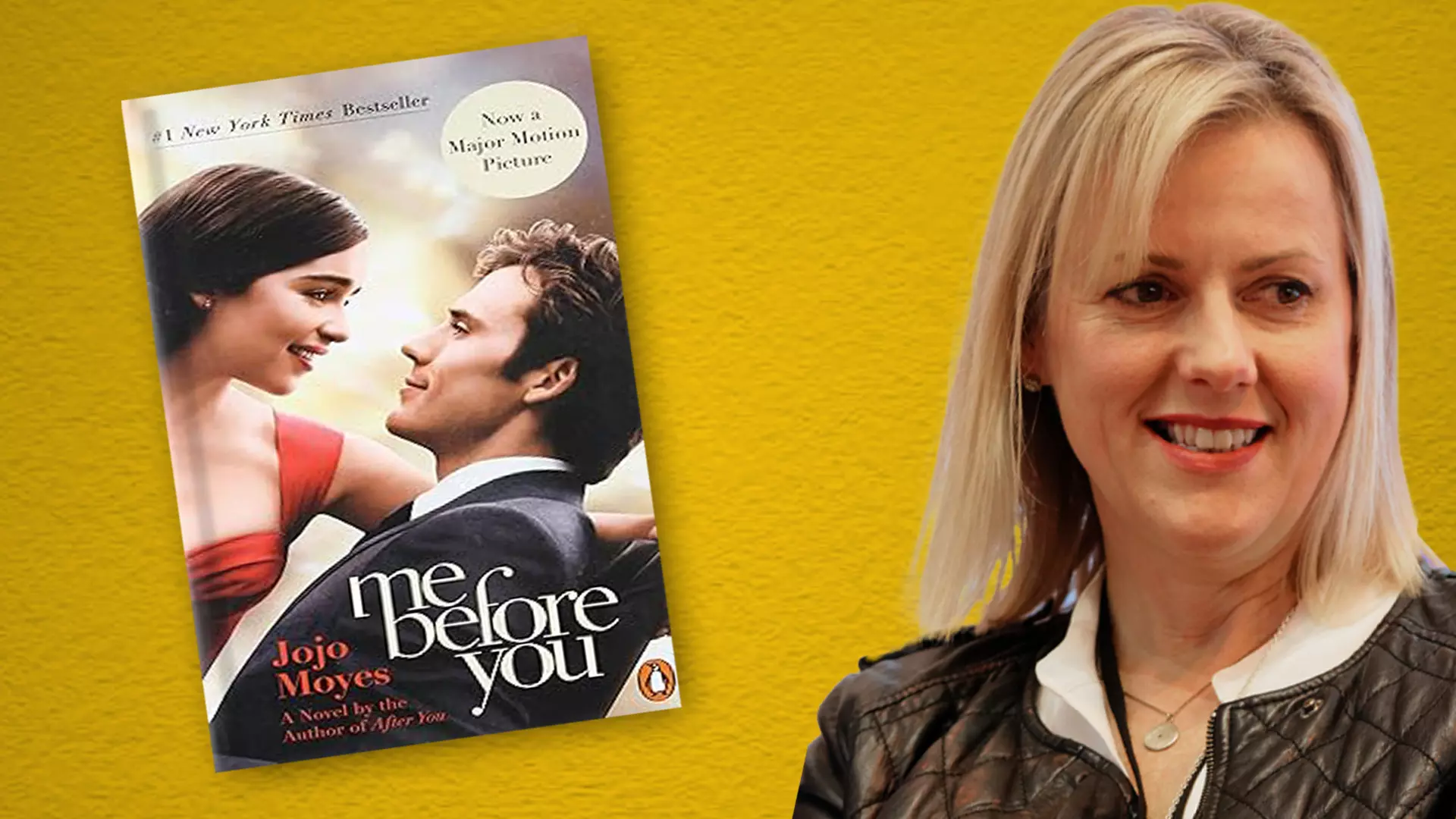

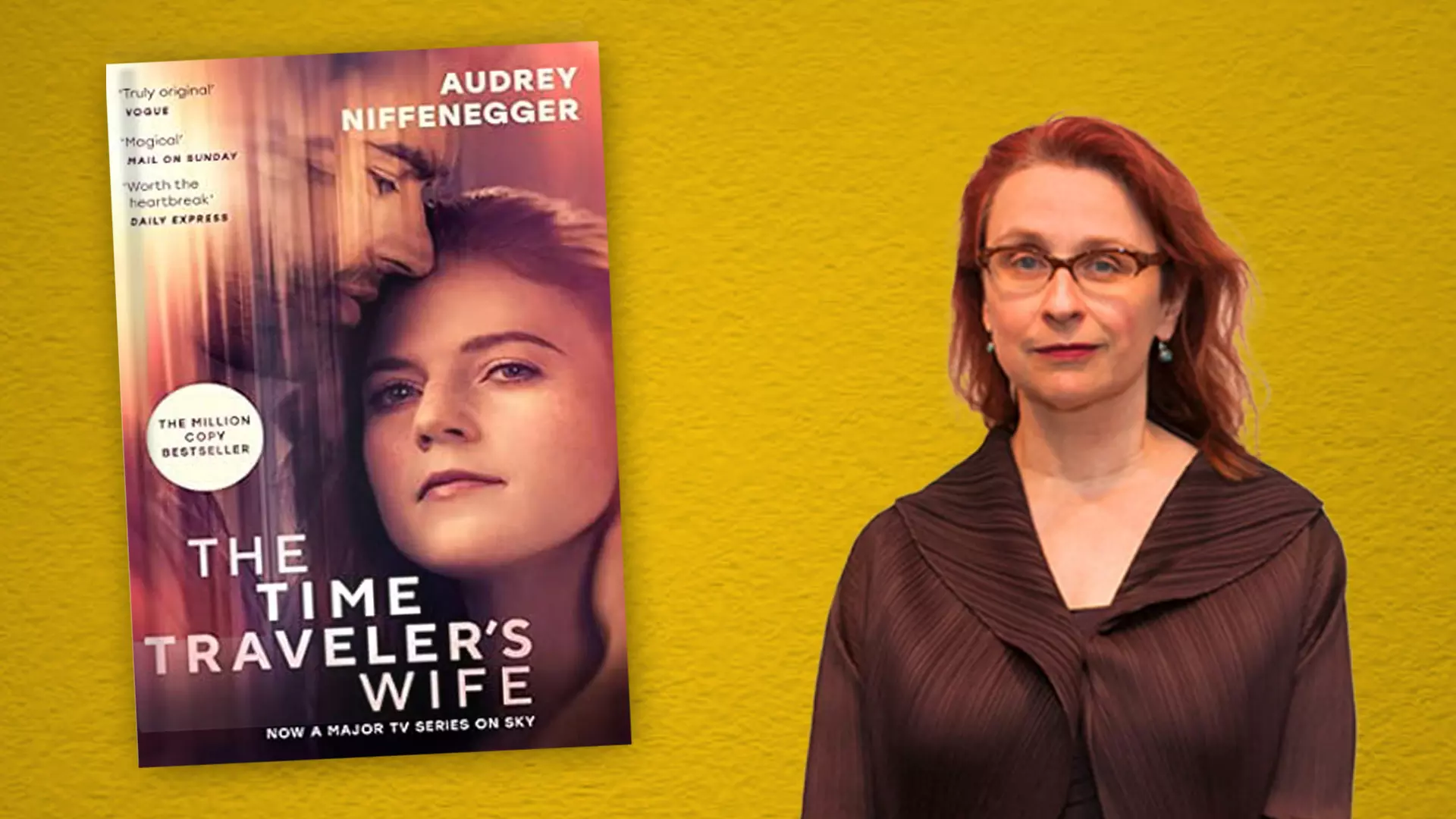

Changing social attitudes, the feminist movement, the rise of social media, and an increasing focus on intersectionality have all contributed to the genre’s newfound popularity amongst the masses. Not to forget that pop-culture icon, think Taylor Swift to Ariana Grande, movie and series adaptions of popular romance books – The Kissing Booth by Beth Reekles (Penguin Random House, 2012), Me Before You by Jojo Moyes (Penguin Books, 2012) or Bridgeton series by Julia Quinn (Harper Collins, 2000) in recent times or earlier adaptions like – Bridget Jones’s Diary by Helen Fielding (Picador, 1996) or The Time Traveler's Wife by Audrey Niffenegger (MacAdam/Cage, 2003) have all played their own big and small roles in remoulding public opinion, allowing people to experience a story that despite being a romance, has so much more to offer.

A quick look at the bestselling charts in the world: New York Times, USA Today, or the Crossword bestsellers, will tell you that it is no longer John Green, Nicholas Sparks or Ravinder Singh who are hitting these charts today as often they once used to. In the words of popular film critic, Sucharita Tyagi, "women telling women stories" have now taken the lead. And why would it not? Women romance writers – Emily Henry, Chloe Liese, Lynn Painter, Nisha Sharma, Nona Uppal, and Stuti Changle, among others – feature not just two people falling in (or out) of love but also characters that are fully developed, multi-faceted, who deal with very human aspects of life like – marriage, family and children, work and occupation, sex and desire, to darker, complex issues such as abuse, mental health, grief, illness, and failures.

It was quite common to have romance stories where a man and a woman fell in love. Overwhelmingly, they would be white, perhaps native Americans or Britishers, celebrating Christmas and eating porridge for supper. The transformative power of this genre is such that one does not always need to fully relate or share in the experience with the protagonist to grasp the story and empathize with them, though one cannot deny the fact that representation, especially of different cultures, ethnicities, abilities, and gender identities and sexualities are an increasingly relevant point and necessary for discussion. This isn’t to say that cis white women authors from Western countries are writing formulaic stories with done-to-death tropes hidden under cute covers and we should stop consuming them. One should, most of them are swoony and worth the time. But the general growing consensus is that the need and space for representation is growing with each new book, like Sandhya Menon’s When Dimple Met Rishi (Hodder & Stoughton, 2017), Naina Kumar’s Say You Will Be My Jaan (Penguin, 2024), Sonya Lalli’s Sari, Not Sari (Simon and Schuster, 2022), Sher Lee’s Fake Dates and Mooncakes (Pan Macmillan India, 2023) and Bolu Babalola’s Honey & Spice (Harper Collins, 2022). The genre has started to challenge traditional gender roles, celebrate female agency, make space for minority and queer experiences, and explore the intricacies of love and desire.

The reshaping of the literary landscape for romance seems to be consistently happening, even as we speak, by women writers who are actively infusing the genre with depth, complexity, and emotional resonance. Want a book on divorce? Second Chance at Love? Infertility? Body-image issues? You name it and you will get it. By amplifying diverse voices and perspectives, including POC, BIPOC and queer authors, the transformation of romance into a dynamic and inclusive genre, one that continues to captivate and inspire with fresh, interesting stories is reinventing the wheel and how.

Malayian-Chinese author, Ivy Ngeow of The Straits Times Bestselling book, The American Boyfriend (Penguin Random House SEA, 2023) shares, “I would like to believe that when readers read, they are aiming to broaden their minds not narrow them. Reflecting reality and representing the world we live in now challenges stereotypes and misconceptions of race, identity and diversity and thus having multicultural characters in romance empowers and inspires marginalised communities who will identify with those characters, which promotes a richness and empathy in the reading experience.

“Even a war novel, like my latest The Man Who Lost India (Simon and Schuster India, 2024),” Meghna Pant asserts, “is about love. About those who survive for love, and those who survive despite love. By showing a forbidden love between a mistress and her help, or an Indian man and a Chinese woman, I paint a large canvas of love and cast it prism-like in several lights to reflect our lives, all shades of it.”

Serving both as a mirror and a window, reflecting our own experiences while offering glimpses into diverse worlds and perspectives, women romance writers now seem to be even more mindful of the genre’s growing sentiments of bringing about a positive change in society. Payal Doshi, author of A Confluence of Fates in the Young-Adult Romance anthology, My Big, Fat Desi Wedding (Page Street YA, 2024) eloquently expresses, “It came down to the joy of writing a story that features South Asian love.”

Canadian bureaucrat by day and a romance author by night, Amy Lea of several internationally best-selling books, including Exes and O’s (Berkley, 2023) believes, “By providing a platform and the freedom to explore diverse narratives and perspectives, romance novels empower women to craft stories that reflect our experiences and ideals of positive, healthy relationships and intimacy.”

Meanwhile, Elle Gonzales Rose, debut author of queer YA book, Caught In a Bad Fauxmance (Joy Revolution/Get Underlined, 2023) adds, “Giving folks from marginalised backgrounds an opportunity to see their experiences reflected in joyful stories like romances can be so special and impactful, and I know this as it has definitely been for me because it's a reminder that we all deserve our own happy endings.”

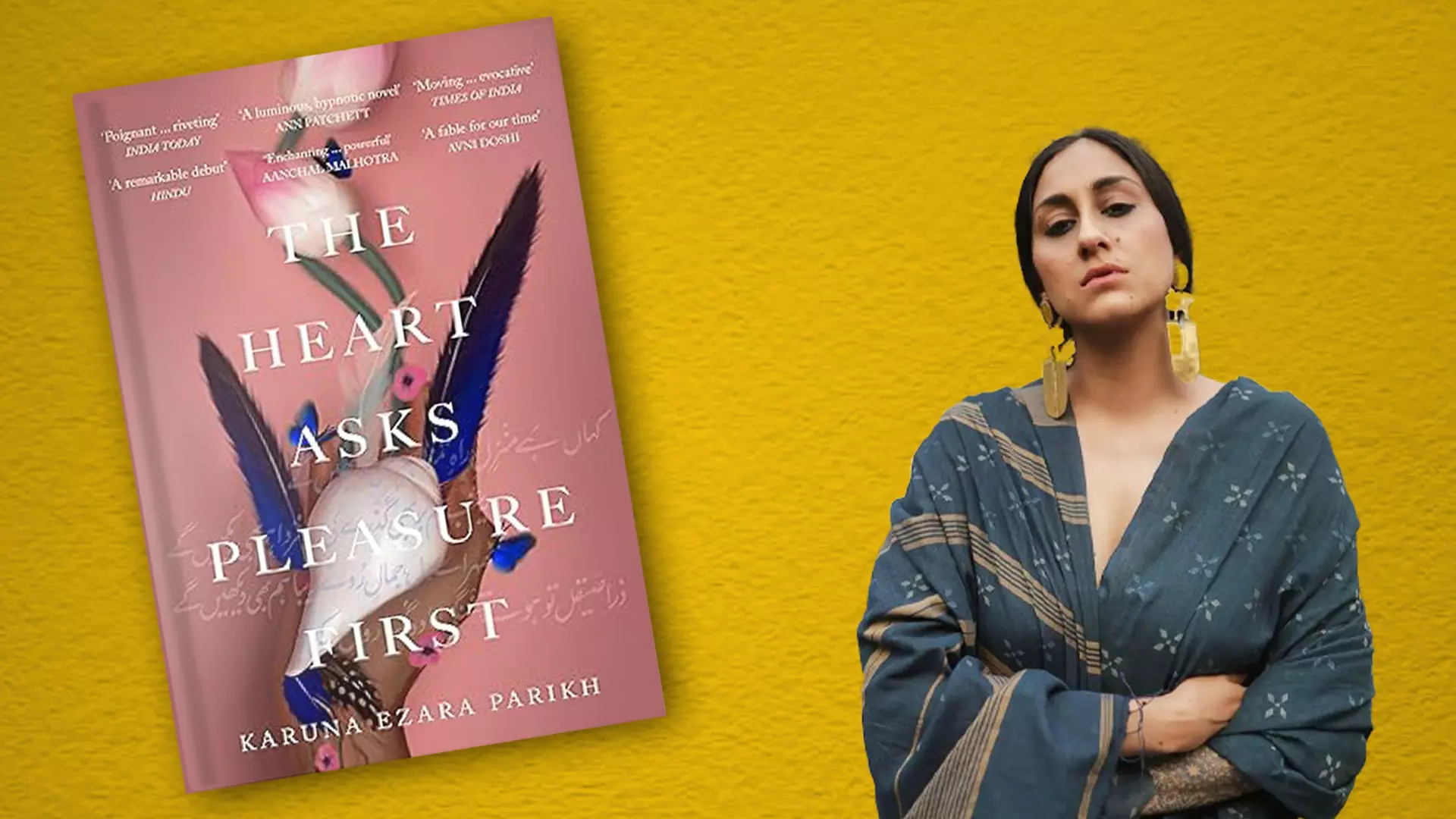

In recent times, the Indian literary scene slowly seems to be also catching up with romance. Some of the books in particular which are worth taking a look, that delve into the colourful and varied palette of our country, are – Milan Vohra’s Our Song (Harper Collins India, 2019) which blends music and pharmaceuticals with a thoughtful NRI romance, Karuna Ezra Parekh’s The Heart Asks Pleasure First (Pan Macmillan India, 2021) where she explores transcendent love, linguistic barriers, and xenophobia, Sakshama Puri Dhariwal’s All That Sizzles (Penguin Random House India, 2023, a fake dating story between a chef and a wedding planner, and Andaleeb Wajid’s The Henna Start-Up (Duckbill, 2023), a young adult novel set in Bangalore with the main character embarking on a journey of entrepreneurship amidst college life's challenges and romance.

Twenty-three-year-old, Kriti Sachan, who has built a robust community of 34 thousand readers on Instagram says, “Reading was always meant to be something one can enjoy, and everyone’s got a different definition of enjoyment.”

As a fellow reader and romance enthusiast, one must agree. It is imperative to acknowledge that personal preferences differ, and one's affinity for a book like Taylor Jenkins Reid’s romance-drama – Daisy Jones and The Six (Penguin, 2019) or Madeline Millers’s The Song of Achilles (Ecco Press, 2011) should not diminish their status as a discerning reader, regardless of their choice to engage (or not) with a literary fiction or non-fiction.

In the end, it all comes down to being content with a read, and if a romance does that successfully thanks to the brilliant stories of all kinds that now exist in the world, one shouldn’t worry so much about picking it up. As Mica De Leon, author of a Filipino workplace romance set in the publishing industry, Love On The Second Read (Penguin Random House SEA, 2023), reiterates, “No matter where we are in the world, no matter the colour of our skins, no matter our upbringing, we all just want to love and be loved. And we all just want happiness—or at the very least a cure for loneliness.”

And so, as the metro approaches the next station, Kirti Nagar, the young woman carefully places her bookmark into her book, almost nearing the end of the story, and gets ready to hop off. As she does, in another coach, on the same metro, a man adorned in a quirky bright tee and tote that says ‘Main Character Energy’ settles into a seat, clutching a rusty copy of Alice Oseman's Heartstopper Volume 4 (Hodder Children’s Book, 2021) – a tender portrayal of teenage queer love. Here, in the bustling heart of the city, amidst the chaos, one stands witness to the enduring allure of romance novels and the space that women writers have built for themselves.