- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

How Putin the strongman would emerge out of the Russia-Ukraine war

Mid of March, Vladimir Putin won the re-election to Russian Presidentship by a landslide, garnering 87.28% votes. As expected the response was mixed. The media and the political leaders in the West described the elections as a rigged one. But inside war-ravaged Russia itself, there was no protest. Russians have voted overwhelmingly for Putin.In a US State Department statement issued on March...

Mid of March, Vladimir Putin won the re-election to Russian Presidentship by a landslide, garnering 87.28% votes. As expected the response was mixed. The media and the political leaders in the West described the elections as a rigged one. But inside war-ravaged Russia itself, there was no protest. Russians have voted overwhelmingly for Putin.

In a US State Department statement issued on March 19, 2024, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that Russian elections did not meet democratic standards citing repression against those critical of authorities, the killing, imprisonment, and exiling of opposition leaders, and denial of registration to anti-war candidates as reasons. However, Russia had invited delegations from 36 countries to monitor the elections and none of them came up with any report of the polls being unfair.

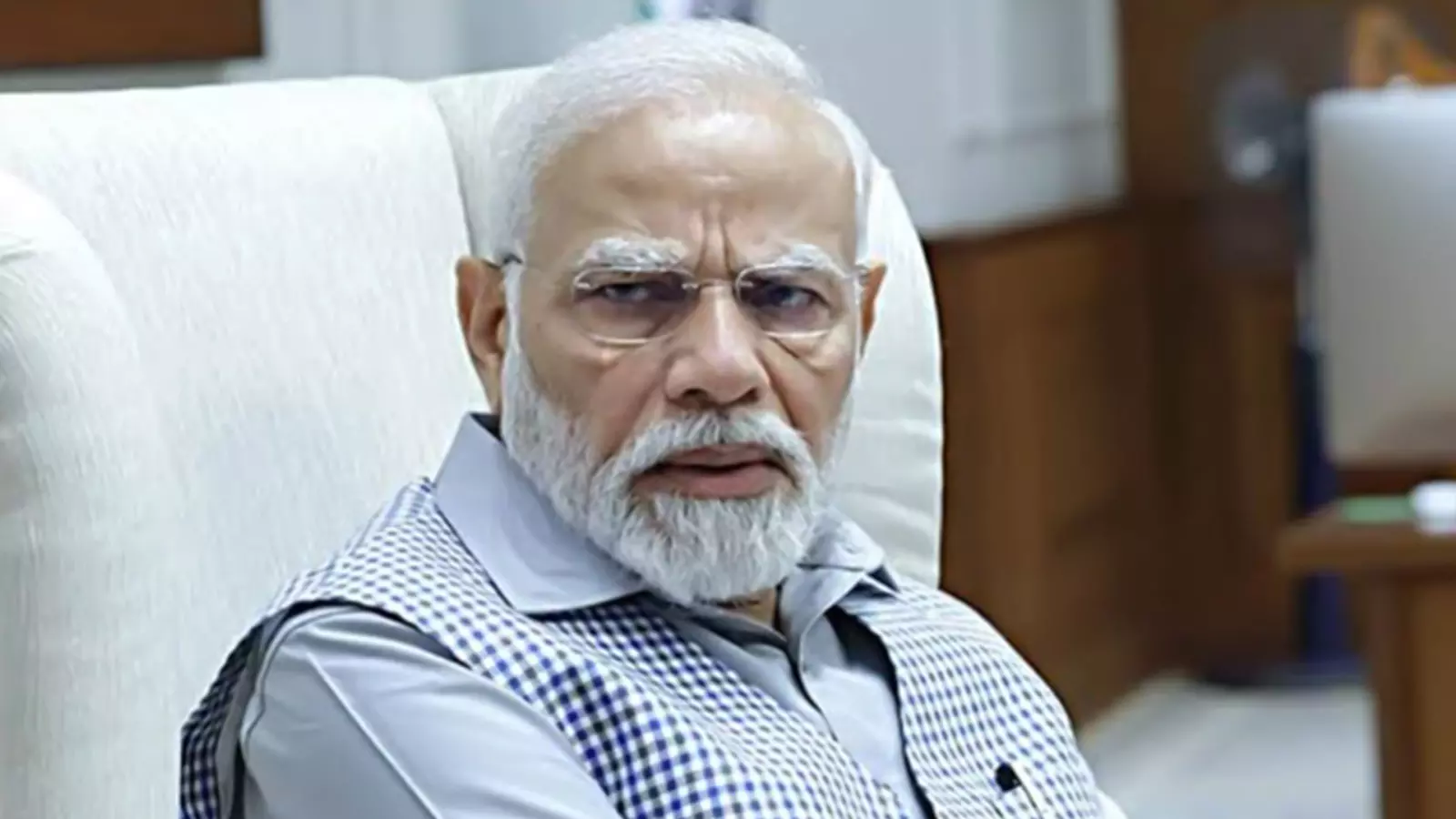

On the other side of the geopolitical divide, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping congratulated Putin for the victory. While Modi hoped that the victory would strengthen the strategic partnership between Russia and India, Xi Jinping underlined that the victory “demonstrated people’s support to Putin”.

While Narendra Modi hoped that Vladimir Putins victory would strengthen the strategic partnership between Russia and India, Xi Jinping underlined that the victory “demonstrated people’s support to Putin. Photos: PTI

What makes Putin so popular with the Russian people that getting elected for the fifth term since 2000 was a mere cakewalk for him? How did he manage to emerge as a colossus on the Russian political scene as well as a towering but controversial personality on the world stage within less than two-and-a-half decades?

Emergence of strong leaders in Russian history

It goes without saying that historic personalities are shaped by the evolving geopolitical forces and prevalent circumstances in one’s own country. Putin is thus a product of a resurgent Russia and also carries the legacy of imperial Russia of late 18th century to mid-20th century.

Russian society has always thrown up towering leaders on the political stage. Upon closer scrutiny, we can find that strong nationalist aspirations were the driving force shaping such outstanding personalities. Whether it was Vladimir the Great of the tenth century or Vladimir II of the following century, the much-hated Ivan the Terrible of the sixteenth century, or Peter the Great of the late seventeenth century or his consort and successor Catherine I of early 18th century, or the ruthless empress Catherine II of the late 18th century, who grabbed power overthrowing her own husband, or the latter Romanovs like Alexanders I to III and Tsar Nicholas who straddled over the rising 19th century Russia, the Russian empire produced several outstanding leaders.

Even post-revolution, there was a politically brilliant Lenin or his successor Stalin, with his share of dictatorial notoriety despite his enormous organising prowess with which he halted the global march of Hitler. Putin is a product and continuation of that legacy. What are the ideological and political underpinnings that make such leaders great?

Putin is the inheritor of Russian nationalism

The nascent forces of modern capitalist economy breaking through the shackles of feudalism in the backward Russian empire generated the first waves of modern nationalist stirrings in 19th and 20th centuries. For all its glorious Czarist legacy, Russia remained a backward economy proving to be no match for the economically advanced Europe.

This difference was at the core of the love-hate relationship that Russia was locked into with Europe. The unique geospatial location of Russia also contributed to its dual character. In modern times, it remained, and aspired to remain, a European power but for all practical purposes it also remained a backward Asian power. The emerging Russian intelligentsia, including the radical Left intelligentsia, deeply aspired to catch up with advanced European economies but at the same time, wanted to maintain their autonomy and independence from European colonial expansionism.

Love and fascination for things European and fear and resistance to Europe at the same time—they were torn by this conflict. This was the new material basis for Russian nationalism of 20th century and Putin symbolizes its 21st century continuum.

Birth of renewed Russian nationalism

On their part, the advanced European countries also never wanted to fully integrate Russia into the European fold. Haunted by Czarist expeditions of the past, they always followed exclusionary policy towards the dreaded despotic Russia with its highly centralised power pyramid around a dictatorial autocrat. In fact, Russia was left out of the European renaissance of the 15th and 16th century. The systemic rivalry between capitalism and socialism reinforced the divide, especially during the days of the Cold War. Even after the systemic divide vanished in late 20th century following the Soviet collapse, the old national rivalries did not diminish. Europe’s distrust of Putin was matched by Putin’s hostility towards the NATO powers.

The Soviet collapse and Russia’s transition to capitalism did not sort out the more fundamental geopolitical differences. True, Soviet collapse did weaken the Russian economy considerably. More than 50% of the GDP got eroded. But Russia quickly recovered, thanks to the oil wealth and abundant mineral resources of Siberia. The huge military machine and nuclear arsenal of Russia remained intact. The new Russian state, especially the KGB-led deep state, quickly found its old moorings and KGB man Putin emerged as the new strongman.

Vladimir Putin won the re-election to Russian Presidentship by a landslide, garnering 87.28% votes. As expected the response was mixed.

The Western leaders never considered Putin as a friend and one amongst them. He was kept at arm’s length. European and American diplomatic manoeuvres began in Central Asia, starting with Ukraine, to create a buffer between Europe and Russia. Putin saw Europe as Russia’s immediate security threat and European powers as vassals and European leaders as mere stooges of the American hegemon, out to further destabilise his regime and Russia. Russian nationalism hence became his natural fallback. Geopolitical power politics thus transcends systemic differences.

Walking along the same authoritarian footsteps

In his personal lifestyle, Putin is bon vivant, who does weightlifting and goes for swimming every day, goes all the way to Siberia to do fishing and loves vacations in his posh Black Sea dacha, and he is very fond of his puppies. When it comes to affairs of state, the same Putin turns into Ivan, the Terrible 2.0.

During the medieval times, Russia remained the heartland of oriental despotism. No Russian leader including Putin is free from the remnants of that despotism. Putin is especially accused of being personally responsible for political murders of opponents, right from the days when he became Director of the Federal Security Bureau (KGB) in 1998–99.

People died in custody. The latest to go is the opposition leader and anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny, the most outspoken critic of Putin. His ‘mistake’ was that he enjoyed a mass following. The public demonstrations he organised against corruption during Putin’s regime were well-attended and well-covered. He was arrested and held in an Arctic penal colony reminiscent of the Gulag. Aged only 47 and not known for any serious ailment, he died mysteriously on February 16 this year. Other opposition leaders alleged that he was killed because negotiations were in an advanced stage for a deal to release him and two other American nationals in exchange for Vladim Krasikov, a high-ranking official in Russian secret service FSB, imprisoned in a German jail. Krasikov was serving life sentence for acting as a hitman killing Khangoshvili, a Chechen dissident who had taken asylum in Germany. Incidentally, FSB is the renamed KGB, loyal to Putin, who had risen up to political leadership from its ranks. Putin himself confessed to agreeing for the swap deal nearly a month later in his famous interview with the US journalist Tucker Carlson to deny any responsibility. In the interview, Putin gave a colourful description of Krasikov as a “patriot” who had been convicted “for eliminating a bandit”.

But critics alleged that Putin could not stand the idea of a free Navalny crusading against him in exile and he got him bumped off to preempt the swap deal.

Navalny was not an isolated case. Another prominent opposition leader Boris Nemtsov was gunned down on a bridge in February 2015. The list is long.

Even two years before he became the president of Russia, immediately after Putin was appointed chief of the dreaded Russian FSB by Yeltsin, Kremlin critic and liberal Duma member Galina Sarovoitova was shot dead in 1998.

Paul Klebnikov, the editor of Russian edition of Forbes was assassinated in Moscow in 2004.

Anna Politkovskaya, the daring journalist who exposed Putin’s crime empire, was gunned down in 2006.

Alexander Litvinenko, an ex-KGB official who became a renowned dissident, was poisoned in London the same year.

Vladimir Kara-Murza, a rights defender, was poisoned in Moscow but he luckily managed to survive but was poisoned again in February 2017 but survived again. He ended up getting 25 years in jail for “treason”.

Boris Berezovsky, a Russian oligarch and Putin’s long-time enemy died mysteriously in London in March 2013.

Aleksandr Perepilichnyi, a Russian businessman and a whistleblower against Putin’s establishment also met with an untimely unexplained death.

Such targeted political killings put even the CIA to shame.

Not only killings, there were numerous cases of arrests of political opponents, especially critics of the Ukraine war.

‘Memorial’, a human rights foundation set up in Russia with funds from Western funding agencies, estimated that in February 2024 there were 680 political prisoners in Russia. Its chief Oleg Orlov is behind bars. Another rights group OVD-Info said 1,143 people were behind bars in Russia on political charges.

Demonstrations organized by Navalny were broken up with force and hundreds were jailed. Publications critical of Putin were shut down.

Reminiscent of what happened in India and Turkiye, there was a witch-hunt against NGOs operating with Western funding and Putin himself alleged that George Soros-funded NGOs like Common Cause were CIA agents.

Not only opposition leaders and political activists, Putin did not spare LGBTQ activists and mafia gangsters even. One of the prominent mafia victims of Putin was Yevgeny Prigozhin, don of the Wagner Group, a mercenary outfit, who was a close supporter of Putin but he turned a dissident by June 2023 and led a mutiny. He died in a mysterious plane crash on August 23, 2023, on his way to St. Petersburg from Moscow.

Several mafia groups dominate public life in Russia and Putin is known to be the patron for most of them. The biggest among the Russian mafia groups is headed by Semion Mogilevich and Putin’s working relationship with him has been confirmed by Russian officials who had taken refuge in European countries. Political dissidents face threat to their lives from these mafia gangs and mercenaries acting at the behest of Putin who has emerged as the supreme Russian mafia don, critics allege.

Putin, the warmonger

Putin could get away with such ruthless trampling of democratic rights because his annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 made him immensely popular with Russians. He became a cult figure among Russians. But the ‘strongman’ had a very deep sense of insecurity. When there were proposals for Ukraine joining NATO, Putin feared that NATO missiles would be deployed at Russia’s doorstep. He launched a full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine and projected it as a supreme nationalist act.

Ukraine war became the defining moment of Putin’s foreign policy. But, similar to the earlier Afghan quagmire, Russia is now bleeding, stuck in Ukraine for more than two years without any sign of early victory. Out of sheer frustration, Putin even talks of escalating the war with the use of nuclear missiles and even threatens the West European countries. No lesson has sunk in obviously from the Ukraine deadlock.

The foreign policy of Russia now has a distinct Putin imprint. The US Senate Intelligence Committee headed by Mueller in its report confirmed that Putin’s intervention in American electoral process to back Trump was “sweeping and systematic”. Trump might have escaped penal action but the episode revealed how vulnerable the world’s strongest democracy was at the hands of Putin’s manipulations.

Though the tussle in the triangular diplomacy involving the US, Russia and China has brought Russia closer to China, China and Russia always had some mutual suspicions and reservations in the Asian power balance. When Putin visited Beijing in October 2023, both declared there were no limits to their friendship. What are the actual deliverables of this “limitless” friendship? Russia-China two-way trade in 2022 was $304 billion whereas US-China trade in 2022 was more than double at $758 billion.

Between 2018 and 2011, China imported $3.5 billion worth of arms from Russia whereas the arms imports by India in the same period were $8.2 billion. After Ukraine war, Russian military imports from China almost doubled. However, North Korea supplies more military hardware to Russia than China. So Putin’s new love affair with China has not started yielding impressive material results yet.

Russian economy under Putin

Russian economy under Putin doesn’t present a rosy picture. Putin thrives mainly on oil revenues and arms sales. Oil revenues worked out to $100 billion in 2023 and Russia’s gas and oil supply to Europe alone earns revenue of around $65 billion. Now, after the Ukraine war, the supplies have been cut and the revenues would dwindle. But Russian crude and petro products supplies to EU are now routed through India compensating partly. Oil sector accounts for 20% of Russian GDP.

In contrast, Russia’s military expenditure in 2022 was $81.7 billion, up from $47 billion in 2021 before the war. Putin himself declared that Russia’s arms exports dwindled in 2022 to $8 billion from $21 billion the previous year. In contrast, the US arms exports in 2022 were $154 billion registering an increase from $103 billion in 2021, the increase mainly accounted for arms purchased from the US companies to supply to Ukraine. Putin’s war has spurred arms industries in Russia. As many as 3.5 million Russians or 2.5% of the population is working in the arms industry. Putin’s hawkish policy does have some material foundations indeed.

How long can Putin can go on with the war

In February 2024, the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated that Putin can sustain the Ukraine war for another 2 to 3 years. The Atlantic Council estimated in December 2023 that Russian casualties in Ukraine, those killed and injured, numbered 3,15,000. The material losses to Russia have also been heavy. Russia has lost around 8,800 armoured vehicles and 20 vessels of its Black Sea fleet sunk. At this rate, the impact on the economy might intensify the dissent within the Russian establishment and Putin will have to make a climb down and come to the negotiation table to end the war. Will the strongman remain equally strong as in the past remains to be seen.